The ‘March on Bellinzona’ and the failure of Swiss fascism

A century ago, the spectre of fascism was haunting Europe. In parts of Switzerland, movements sprang up in support of Mussolini’s dictatorship in neighbouring Italy. Historian Yves H. Schumacher looks back on the failed attempt to bring fascism to the Alpine state.

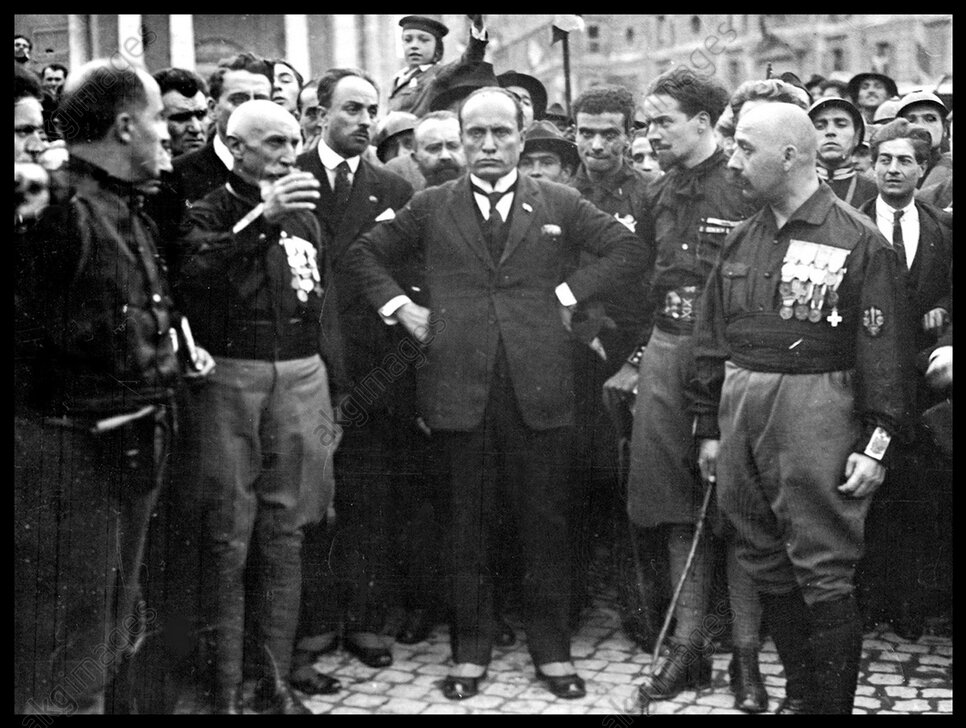

On October 28, 1922, it was crisis time in Italy. Fascist militants, 50,000-strong, marched on to Rome. Benito Mussolini seized power, helped by King Vittorio Emanuele III, who commissioned him to form a new government. The Duce thus embarked on more than twenty years of totalitarian rule.

In Switzerland, Mussolini’s takeover sparked applause in several quarters, not least in Lausanne, the hotbed of fascism at the time. Here, back in 1902, the young Mussolini, dodging military service in Italy, had made a small income working as a messenger and doing odd jobs. Soon he was making a name for himself among the Italian community in canton Vaud, building his profile with fiery speeches and provocative articles in the newspaper L’Avvenire del lavoratore. In 1904 he left Switzerland, having made his mark as an agitator in this country.

Malaise after the Great War

Twenty years later, following the General Strike of 1918, a political malaise took hold in Switzerland. While the left admired revolutionary Russia as the model of a just society, many liberals and right-leaning Catholics saw in Fascist Italy a bulwark against communism. The right was deeply distrustful of the Swiss government and wanted to see a strong hand take over.

Even the conservative-leaning Swiss General Henri Guisan was impressed by Mussolini’s rise to power – at least, until the Duce sought an alliance with Adolf Hitler. In 1934 Guisan praised the Duce in a report to the federal defence ministry: “The great quality of this man, this genius, is that he has succeeded in disciplining all the forces of the nation, uniting them into a single stream and using this stream solely for the greatness of his country.”

In January 1937 the University of Lausanne conferred an honorary doctorate on Mussolini. Even at that time, fierce criticism followed this decision.

Alongside Geneva native Georges Oltramare, Arthur Fonjallaz of Vaud emerged as a leading figure of Swiss Italo-fascism. Fonjallaz had a successful military career and advanced to the rank of brigadier-colonel. He had already made known his enthusiasm for fascism in 1922, after meeting Mussolini for the first time. In 1923 he left the Swiss army and became a lecturer in military studies at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. He hoped to attain the rank of full professor there. In this he was not successful.

Offended, Fonjallaz looked for scapegoats, and attributed the denial of a promotion to a Masonic plot. In 1933 the federal government took up the matter of his teaching position, and pushed him to resign. In that same year, in Rome, Fonjallaz founded the Swiss Fascist Movement, based on the National Fascist Party of Italy. At least 15 times he had personal dealings with Mussolini, who supplied him with funding to the tune of CHF600,000.

Planning a ‘march on Bellinzona’

Italy’s drive to enlarge its borders was justified by a particular idea: irredentism. According to this doctrine, the Italian- and Romansh-speaking populations of Switzerland were “unredeemed brothers in blood and language”, who ought to become part of the Italian empire. This absurd notion attracted a few people in Ticino, for just one reason: the increase in the population of German-speakers in the canton, accompanied by what they saw as disregard for Italian culture.

Most Ticinese were not taken in by the propaganda from Italy. There was, however, a hard core of right-wing extremists in Ticino, who proved a nuisance to the federal government.

One of the main fascist campaigners in the region was the wealthy engineer Nino Rezzonico, whom Fonjallaz appointed as his second-in-command for Italian-speaking Switzerland in October 1933. Fonjallaz also entrusted him with the task of setting up the umbrella organisation, the Ticino Fascist Federation.

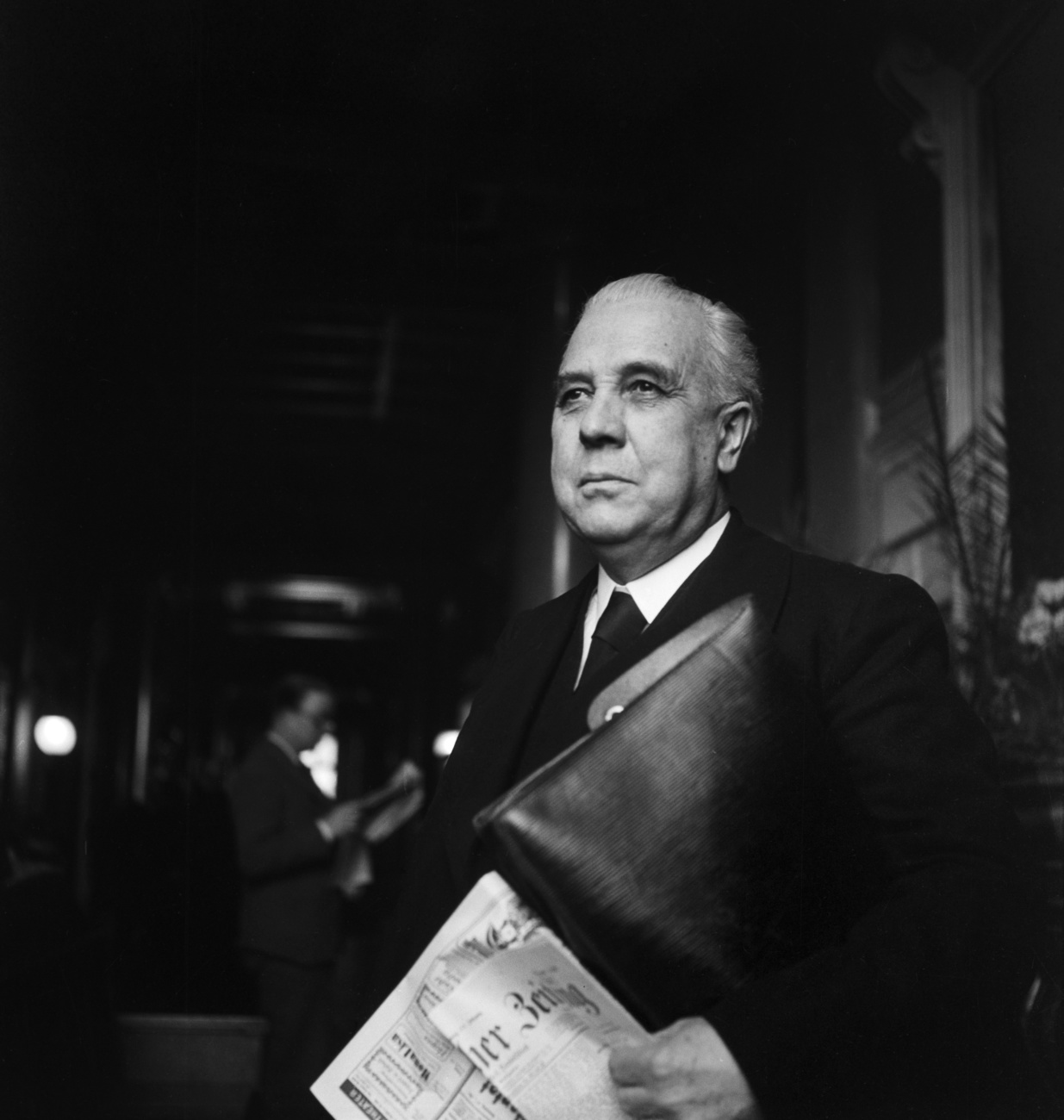

With the intention of founding a Fascio (local group) made up of Swiss expatriates in Milan, Rezzonico contacted a prominent member of the Swiss Chamber of Commerce in Italy at the end of that year. After a strategy meeting with his contacts across the border, Fonjallaz proudly informed the Duce of his plan to set up a Swiss Fascio in Milan with a initial group of about fifty fascists. But it came to nothing. Two opposing camps made up the Milanese Swiss community. The hostility between them reached boiling point. The Swiss envoy in Rome, Georges Wagnière, was forced to intervene.

If Mussolini had succeeded in rising to power with his March on Rome, Rezzonico reasoned, he should also succeed with a “March on Bellinzona”, the capital of the canton, in forcing the collapse of the Ticino government.

On January 25, 1934, Rezzonico’s men assembled in Lugano. They got ready to march on Bellinzona, with the aim of occupying the seat of government and demanding annexation to Italy. This irredentist action failed to arouse enthusiasm even among the Italians living in Ticino, who largely ignored it. In the end, no more than about 60 armed militants marched on the government buildings. There they encountered some 400 anti-fascists massed before the doors of the parliament building. Little actually happened except for a few scuffles. The fascists’ plan to take over the government simply evaporated.

As a result of this fiasco and the ensuing internal power struggles, Rezzonico was expelled from the leadership of the Ticino Fascist Federation. He then withdrew for a time to his property in Turin.

The Rome-Berlin Axis and the Wehrmacht’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939 opened the eyes of most of the Ticino fascists, and the united front hoped for by the German-speaking National Front failed to materialise. When Italy entered the war nine months later, it turned out to be the death-knell of fascism in Switzerland.

In 1941 Fonjallaz was arrested for spying and eventually sent to prison for three years. Rezzonico reappeared in Porzo near Lugano around this time, and from then on maintained a low profile as a local politician and journalist.

Yves H. Schumacher is the author of the 2019 book Nazis! Faschistes! Fascisti! Faschismus in der Schweiz 1918-1940, (Nazis, Fascists and Fascism in Switzerland, 1918-1940) published by Orell Füssli and currently out of print. A revised second edition, published by Zocher&Peter, is to appear in 2023.

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.