The Swiss henchman of America’s ethnocide

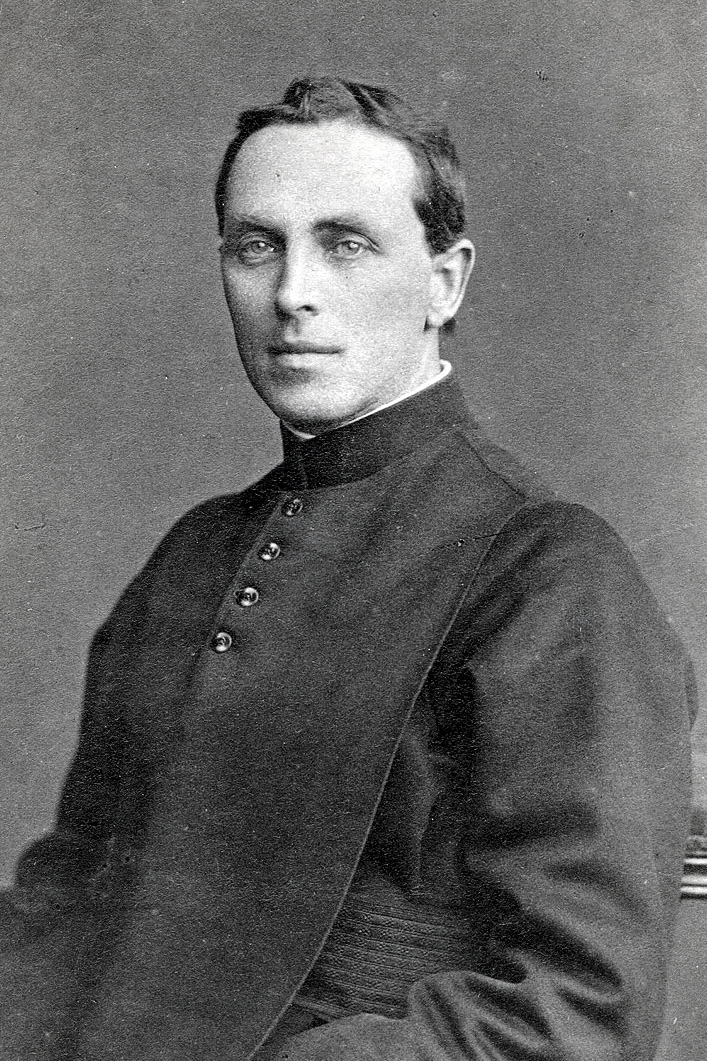

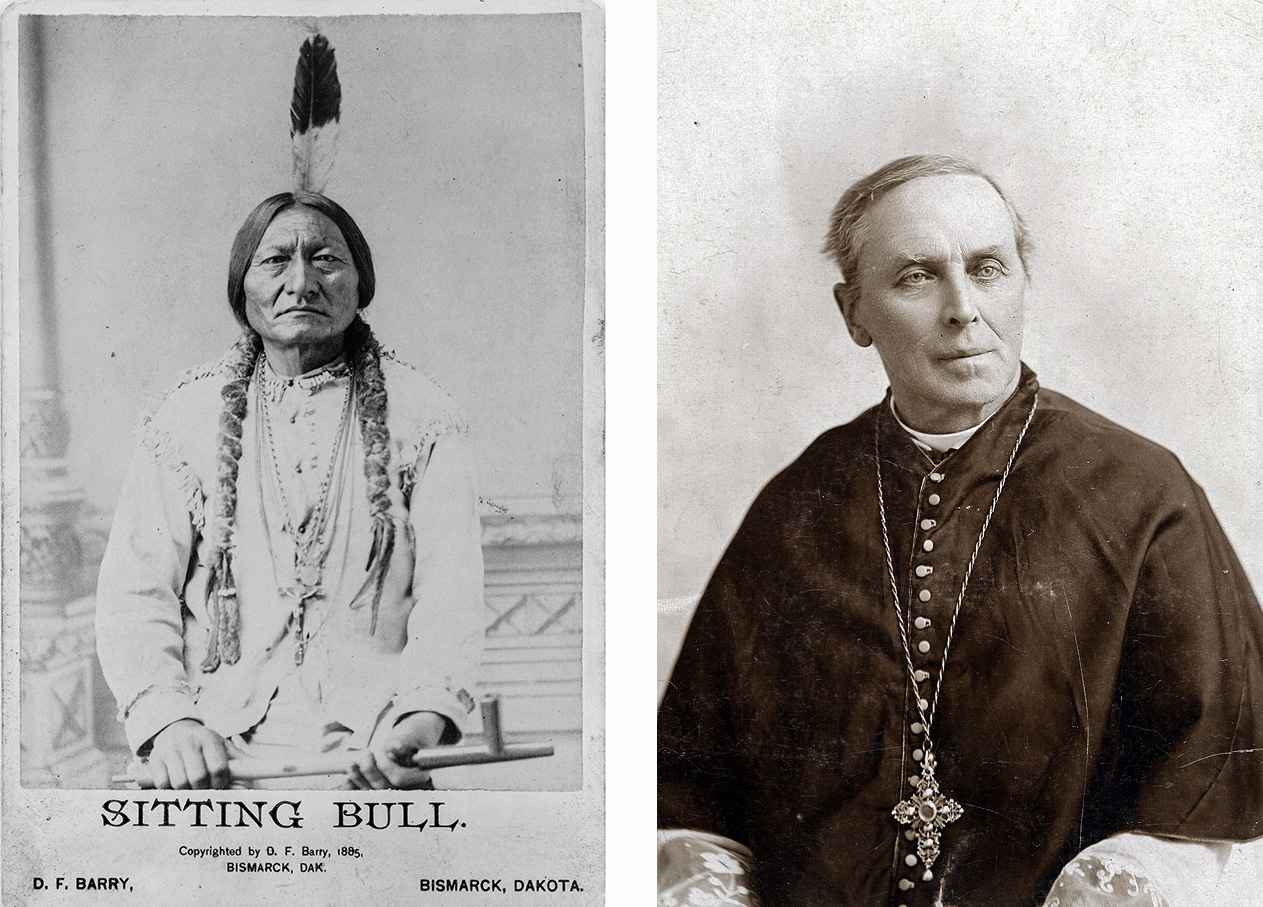

Martin Marty’s mission was to save the Sioux tribes from hellfire; he even attempted to convert the infamous “Sitting Bull” to Catholicism. This made him part of the US drive to annihilate Native American culture. How did a Swiss-born Benedictine monk end up “civilising” indigenous people on behalf of the American government?

The Bishop Marty Memorial Chapel in Yankton, South-Dakota was erected in the years following WWII to serve as a “monument for the holy bishop who brought the Benedictines to Dakota”. Martin Marty’s zeal for the “Indian Missions” earned him the title “The Apostle of the Sioux”, and many schools as well as a small village are named after him.

One of the stained-glass windows in the chapel serves as a reminder of how Marty (unsuccessfully) tried to convert the hostile Sioux Indian Chief Sitting Bull just before he was shot dead. The window depicts how Marty looks up to the big chief in awe with a group of indigenous women holding a songbook and singing in the background.

The Swiss historian Manuel Menrath, who diligently researched Marty’s story and his role in the “civilisation” of the Sioux, views this depiction as irritatingly hypocritical.

“Marty is shown devoutly singing with long-haired Native Americans wearing stereotypical headdresses. They would have got away with it in heaven, however, it was a different story at the boarding schools run by Marty: headdresses and hair were the first things to go as they were considered pagan and devilish,” he writes in his biography of the missionary.

It is also Marty’s doing that many Sioux are still Catholic to this day. His boarding schools were part of the attempt to turn indigenous children into efficient and diligent Americans, and above all into Catholics. Marty is a prime example of how a religiously oriented man became a henchman for colonialism. But how did a Swiss-born monk end up in the US in the 19th century?

Marty’s attraction to the Wild West

As the son of a shoemaker and church sexton, Marty and his three brothers, who all became priests, grew up in church. From the age of five, he attended a Jesuit-run school which quickly kindled his enthusiasm for the Jesuits’ work as missionaries of their faith. One of his idols was Saint Francis Xavier who did missionary work in Japan, Mozambique and India in the 16th century. Even though Xavier never ventured to North America, people in central Switzerland worshipped him as an “Indian missionary” during this time.

For Marty, however, it was too late to become a Jesuit in Switzerland. They were considered subversive and only obligated to Rome. The Jesuits were finally expelled under Switzerland’s first federal constitution, which was drafted in 1848. At the young age of 16, Marty became a Benedictine monk and received the religious name “Martin”.

The dominance of Protestant cantons, where many monasteries and colleges were closed, also had an impact on other Swiss Catholics. Einsiedeln Abbey, which Marty was affiliated to, was looking for ways to avoid secularisation. And so Swiss monks went to the US and founded the Benedictine Saint Meinrad Abbey in Indiana near Tell City, where many Swiss settled in the 1850s.

These settlers were not only looking for a refuge, but, according to Menrath, they followed the Catholic emigrants. There was a fear that they might convert to Protestantism in a foreign country.

However, Saint Meinrad Abbey in the “Wild West” did not live up to the standards of Einsiedeln Abbey in Switzerland. In 1860, 26-year-old Marty was deployed to the US to sort things out, and he did. He set up a school for the settlers’ children which attracted more people who built a village around it. In 1870, Saint Meinrad was upgraded to an independent abbey, with Marty elected as its first abbot.

But Marty was not a fan of sedentary monastery life. He strived to become part of the frontier mission movement as a travelling missionary. His goal was to enlighten the “pagans in darkness and the shadow of death” with the Catholic truth. Even though he had gone to the US as monastic cleric, his heartfelt wish was to become an “Indian missionary”, and his dream was slowly coming true. Times were favourable.

More

Gallery of Sitting Bull

‘Civilisation’ instead of annihilation

After the Civil War, a sense of battle fatigue swept North America, which also affected the drive to convert the Native Americans. Humanists and church representatives called for less violent interactions with indigenous people. According to the then interior minister, the “helpless and benighted race” should be educated following the “teachings of our higher Christian civilisation”.

Biographer Menrath does not believe that this mission was about introducing equality or creating a new Native American elite. He reckons it was designed to produce maids, factory workers and good Christians that society could benefit from.

Churches of all different religions started to come into play. The reservations, into which the tribes were forced to move under the threat of execution, were allocated to various missionary organisations. Those who were doing the most missionary work on the ground got the job.

It is important to note that the peace policy did not put an end to the annihilation of Native Americans. It was rather America’s last attempt to eliminate their language, culture and spirituality. Today this would be called ethnocide. According to Menrath, such programmes are typical of settler-dominated colonialism which was also prevalent in Australia and New Zealand.

“At the beginning it always seems idyllic – settlers move to a region, they use a bit of land, and the natives continue their nomadic life. Live and let live. But suddenly, the colonialists need more land, and the natives are in their way. This leaves two possibilities: annihilation and re-education,” notes Menrath in his book.

Settler colonialism does not necessarily require the settlers to have the same nationality as the colonial power. There are endless opportunities for people of all nations to participate – as long as they are part of the race that is considered ‘superior’. This allowed Marty to play an important role in colonialism.

Menrath warns of being too quick to judge or hasty in condemning the church. According to him, these programmes were launched by the state and the clergies thought they were doing something worthwhile by supporting this new policy.

Marty‘s ‘civilisation institutions’

When the “Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions” established in 1874 asked Marty to join them as a missionary, he jumped at the opportunity. Despite his position as abbot, he left Saint Meinrad Abbey in 1876 to devout his life to converting the Sioux in the Standing Rock Reservation.

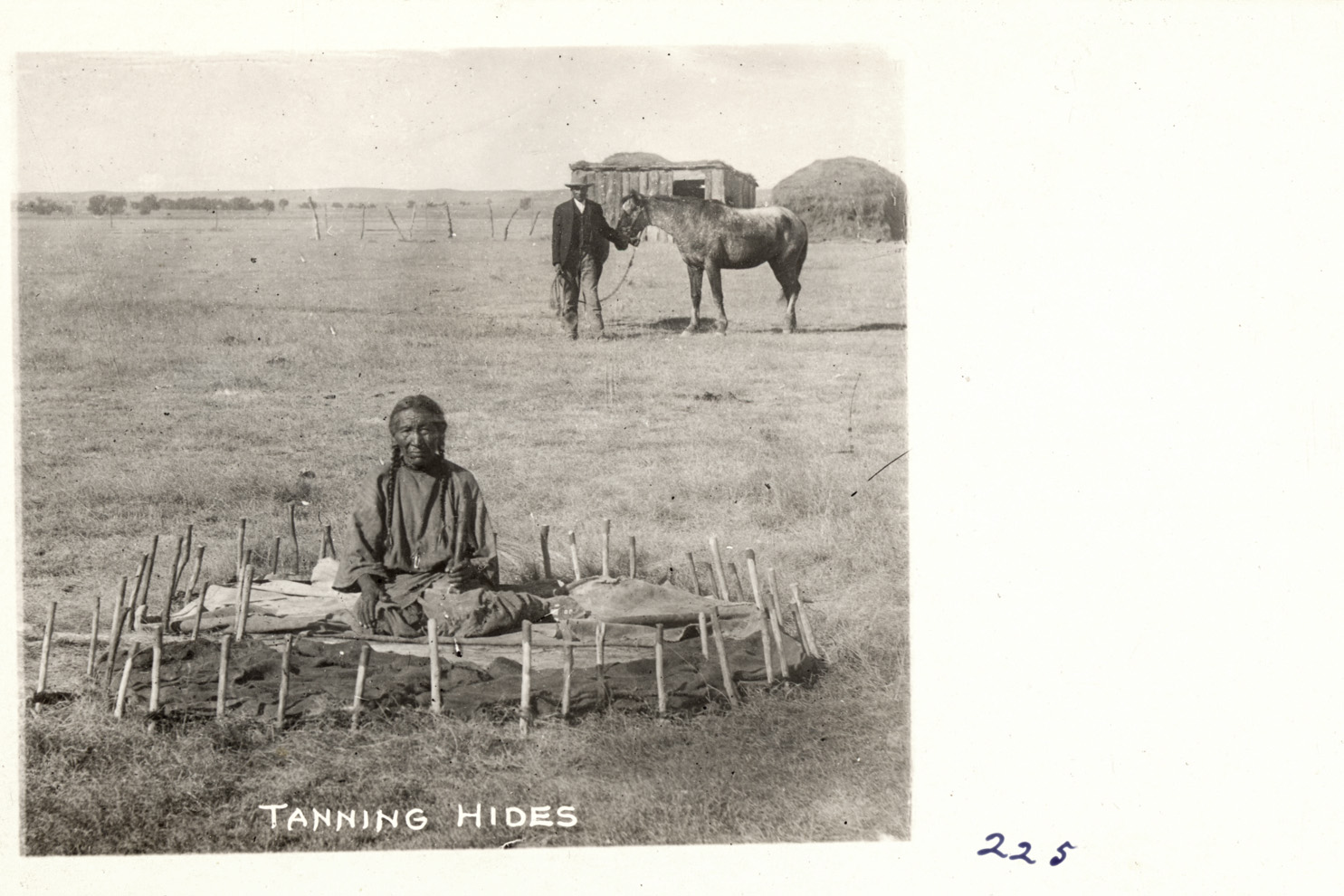

Marty repeatedly criticised the violent policies against indigenous people. He blamed the heavy-handed US approach for turning the Sioux into “loafers, dalliers and beggars.” Nevertheless, he considered their culture to be backward and unworthy of protection. So, he set about dividing the Sioux people and pushing them to adapt European practices of farming.

Very early on, he realised that his work had to focus on children. They seemed more open to “civilisation” than adults and Marty deemed it necessary to separate them from their parents to succeed in his “civilising” mission. The Swiss monk was convinced that there was no point in educating indigenous children if they were regularly allowed to return to their families. The children remained separated from their parents until they reached adulthood. This was to ensure they became “good Catholics” before they went on to start their own families.

In 1876, the Sioux helped Marty build a boarding school. In doing so, Menrath writes, they were completely oblivious to the fact that they were “digging their own cultural grave”. Many parents gave their children voluntarily to Marty and his associates. They did not want them to be taken to the military boarding schools outside the reservations where their chances of survival were slim.

Even before Marty arrived in the US, indigenous children were taken to off-reservation boarding schools to strip them of their original culture which made them an integral part of the “peace policy.” Many of them died. Dormitories were breeding grounds for diseases, and every boarding school had its own cemetery. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School alone buried 190 children.

Marty’s Catholic boarding schools were less harsh in comparison. The children were allowed to speak in their mother tongues. This, however, was more about the success of the mission rather than allowing an expression of the children’s culture. It was believed that the Gospel would have better access to their souls when entering in their mother tongue. However, the pupils’ hair was cut upon arrival and their traditional clothes were replaced with white robes.

Lessons in closed rooms must have been a radical change for the children. In his book, Menrath dwells on the experience of children snatched from a world in which they had lived by natural cycles – the sun, the stars and the seasons – to an environment that was dominated by sharp corners.

“Rectangular desks, beds and doors. Even the forest was replaced by a neat garden with rectangular flower beds,” he writes. “This was almost like raping the Indian soul.”

Spanking and humiliations

The way the children were treated in these Catholic boarding schools was similar to education offered in European institutions until the 20th century. No defiance of the bourgeois concept of society was allowed and rules to enforce discipline were extremely tough.

The children were locked up, humiliated, or beaten up. This was considered legitimate at Christian schools because it was believed that those punished in this world had already done their penance for the afterlife. “Punishing the body would spare the soul greater torment in purgatory,” according to the Swiss historian.

When not working or facing punishment, praying was a big part of life at Catholic schools. Mass was held before the start of the lessons which meant that the children’s daily chores started very early.

“Kill the Indian, and save the man,” was the mantra of the “peace policy”, but that did not always work out. A grotesque case in the Rosebud Indian Reservation in 1890 showed that it was not about saving the man, but the soul. An indigenous father stormed into the boarding school of the Saint Francis mission after the death of his son. He carried his son’s body home to give him a traditional burial, but the nuns were outraged as they did not want the child’s Catholic soul to be lost. The father was arrested, the body of the son confiscated, and the boy was given a Catholic funeral.

When Marty died in 1896, more than 6,000 Sioux were converted Catholics making him one of the most “successful” missionaries in the US. But was his civilisation policy successful?

Menrath has his doubts even if most of the Native American tribes are now Catholics. However, by bringing together children of different tribes, state schools triggered a Pan-American Indian movement.

“Learning how to read and write allowed them to strengthen their culture and turn the reservations into homelands,” he notes in his book. “Even though many suffered and lost their lives: measured against the goal of annihilating everything Native American – the language, the spirituality, the feather decoration, the sacred pipe – ethnocide has failed.”

Manuel Menrath‘s biography of Martin Marty “Mission Sitting Bull, The Story of the Catholic Sioux” was published in 2016. With his book “Under the Northern Light: Canadian Indians Talk about their Land”, Menrath published another account of North America’s indigenous people featuring many contemporary testimonies.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.