Swiss arms exports still at odds with humanitarian tradition

The government’s plan to ease arms export rules has sparked controversy with critics warning it could endanger the neutral country’s reputation and humanitarian tradition. A Swiss historian and author explains how this paradox has been a recurrent theme since the First World War.

Exports of Swiss-produced war materials has been a hot issue in Switzerland in recent months. In June, the government proposed allowing weapons to be exported to countries in the throes of internal conflict, provided it could be established that they would not be used by warring parties. This relaxation has been criticised by activists; on Monday a group announced it was spearheading an initiative campaign in the hope of getting the Swiss authorities to change course.

The historian Cédric CotterExternal link is very familiar with this theme. His PhD thesisExternal link looked at Swiss humanitarian action and neutrality during the First World War, including a section on Swiss weapons exports to the warring parties. A book versionExternal link was published last year.

Cotter’s work shows that the arguments heard over 100 years ago still echo in the ongoing national debate. Today, as then, neutral Switzerland does not officially provide weapons to belligerents, in accordance with a rule laid down in the 1907 Hague Conventions. But the First World War, with its extreme violence, increasingly powerful weapons and duration, resulted in a huge demand for ammunition that Swiss industry was able to meet in large quantities.

“Although Switzerland was no longer able to export ammunition from August 1914, due to international law, there was nothing to stop the export of ammunition parts (brass parts, cast iron, wrought iron and bolts, etc). Thanks to this clever trick, Switzerland was able to deliver millions of rounds to the warring parties,” Cotter explained.

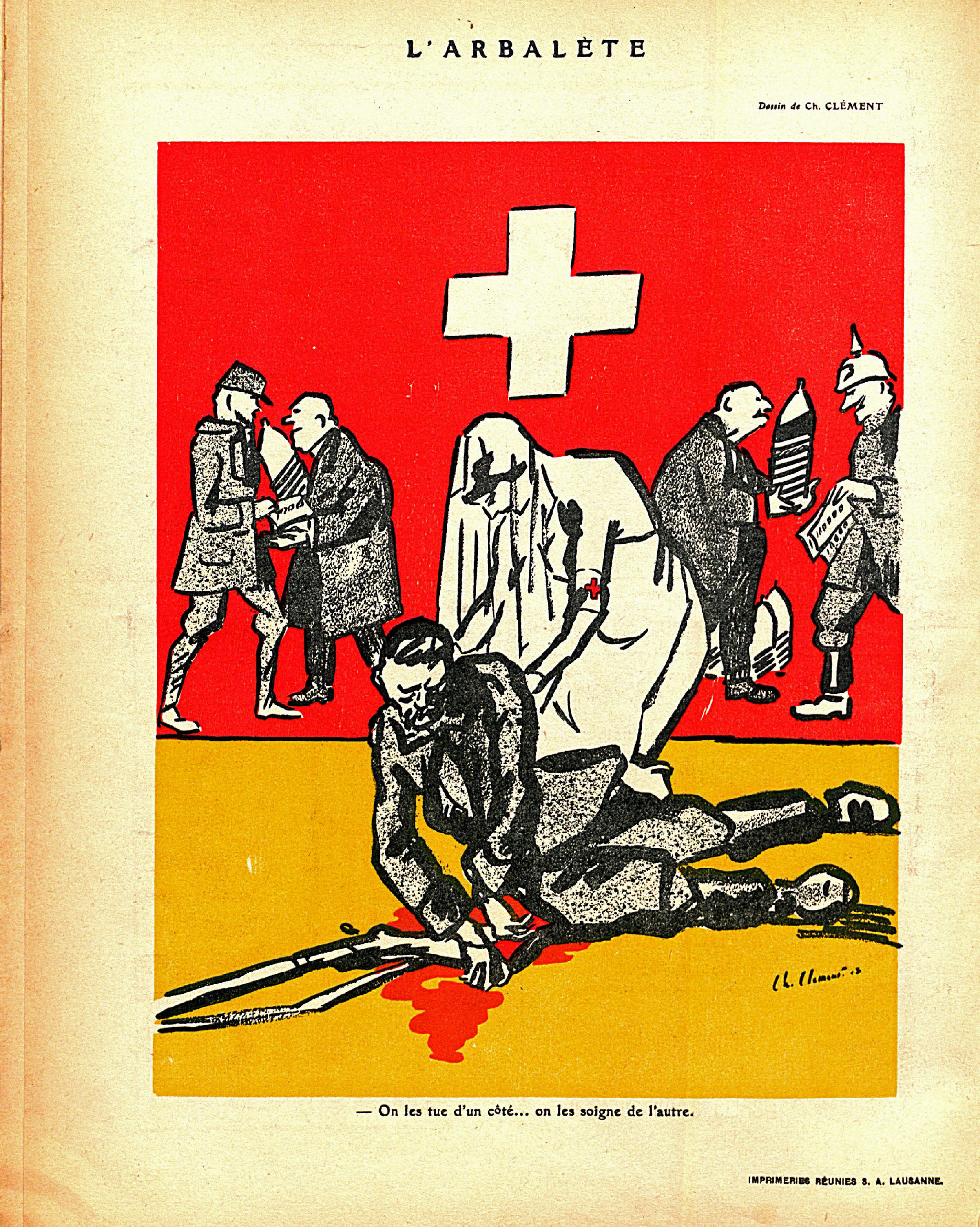

‘We kill them on one side… and care for them on the other’

The historian notes that in 1917, exports of ammunition from Switzerland amounted to CHF300 million – the equivalent of CHF3 billion ($3.1 billion) today, or 13% of Swiss exports that year. In 1916, these exports were worth CHF200 million.

At the same time, the Swiss-run International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), an international humanitarian organisation based in Geneva, expanded its operations due to the huge needs caused by the deadly conflict; in particular the protection of prisoners of war.

“This ambiguous attitude of Switzerland, which sells ammunition with one hand and helps the victims of the war with the other, obviously provokes criticism,” the author declared.

The United States, which was also neutral before entering the war in 1917, was particularly critical.

“An estimate by the American consul in Bern shows one-third of Swiss exports went to Germany; the rest were mainly for France and Italy,” said Cotter.

The issue of Swiss ammunition exports grew in importance nationally from 1915 onwards. The satirical magazine L’Arbalète (The crossbow), had a special December 1917 edition looking at the manufacture of ammunition versus humanitarian work. One cartoon shows Red Cross nurses and the bosses of ammunition firms, while another is subtitled “We kill them on one side… and care for them on the other”.

“While it was aware of the involvement of Swiss industry in the manufacture of ammunition, the Federal Council didn’t ban such activities. It preferred to see this practice continue, creating thousands of jobs for workers, rather than examining it in detail,” said Cotter.

He cited the example of the Geneva car firm Pic-Pic, which quickly turned part of its production into manufacturing artillery shell fuses for the French and British armies.

“In January 1917, the Piccard-Pictet workshops produced 200,000 fuses a week for Britain. Out of the 7,500 staff, 1,500 were factory workers making ammunition, earning CHF0.35-0.40 an hour. At the same time, the firm used to sell other articles to the American Red Cross,” he said.

The boss of the company, Guillaume Pictet, became an ICRC committee member in 1919. The constant back-and-forth between business, the Swiss government and the ICRC has never really stopped since then.

+ The ICRC as a Swiss political tool

“The truth is that Switzerland manages very well with this contradiction. The First World War is characteristic of the Swiss attitude. The same phenomenon can be seen in many other conflicts. The simultaneous existence of an industry manufacturing weapons and humanitarian work is almost ‘traditional’ in Switzerland,” said Cotter.

The other magic formula

He believes, like other specialists, that Bern and the Swiss economy have drawn the greatest benefit from the positive image of the ICRC, even if the Swiss authorities helped the ICRC to gain in stature alongside other humanitarian agencies. In general, all neutral states sought to develop their national image through humanitarian action, and not simply to pass as simple profit-makers from war.

The First World War was nonetheless a highly challenging time for Switzerland: it was split internally between French and German supporters, and it had a military corps that was fascinated by the Prussian army and was suspected of leaning towards Germany. For example, General Ulrich WilleExternal link, a member of the Bismarck family who was appointed by the Swiss parliament in 1914, pushed at the start of the war for Switzerland to fight alongside Germany.

Like elsewhere in Europe, the Swiss government was also feeling the pressure of social conflicts, which were perceived as the result of the Russian Revolution. In 1919, Switzerland emerged from the war at the height of its powers, with Gustave AdorExternal link as president of the Confederation and of the ICRC.

In 1920, Geneva was chosen as the headquarters of the League of Nations – the forerunner of the United Nations – after it recognised Swiss neutrality. Switzerland joined the body after a narrow majority of citizens voted in favour the same year.

Recently, current ICRC President Peter Maurer criticised the Swiss government’s mooted relaxation of war material exports, saying it would damage the country’s humanitarian profile. His criticism is a reminder of a longstanding delicate balancing act. It is possible that Switzerland’s ambiguous position cannot be resolved. The obvious contradiction threatens the existing magic formula, many observers in so-called International Geneva warn, especially at a time when the world is witnessing a new surge in power relations and a weakening of the multilateral system.

More

Uncensored report on arms exports reveals shortcomings

Translated from French by Simon Bradley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.