‘This is about Western perceptions…our relationship to this art’

Bern and Switzerland have more connections to the Russian Revolution than we might at first imagine.

The Bern Museum of Fine Arts and the Paul Klee Centre are looking back 100 years to the October Revolution of 1917 and chronicling the history of revolutionary art with an unusual exhibition called “The Revolution is dead. Long live the Revolution!” The impact of the two art movements which arose from this aesthetic and political revolution is still reverberating in the art world today. swissinfo.ch spoke to the curator of the Bern Museum of Fine Arts, Kathleen Bühler, about the one-sided perspective of the West, propaganda and kitsch, and the political significance of the arts.

Larissa M. Bieler: Kathleen Bühler, the October Revolution in Russia in 1917 shook up the whole of Russian society. A tsarist regime that had survived for centuries collapsed and ended. Why is that a subject for a Swiss art museum?

Kathleen Bühler: It didn’t just shake up Russian society. It shook the whole world. Thematic exhibitions are always a good opportunity to look back at history and at art history and to think about our relationship with the subject today. How does it affect us as a society? The question of the rift between the socialist or communist world and the capitalist world is a pressing one again today. There were various pivotal questions about this historical event which led to this exhibition.

More

The revolution is dead. Long live the revolution!

Larissa M. Bieler: The political forces behind Trump and Brexit see themselves as the leaders of an international protest movement today. Did the idea for this exhibition evolve from this current connection?

Kathleen Bühler: Absolutely. No art museum can limit itself to art-historical debates. Art is the place where the imagination finds space and where hopes seek expression – either with or without censorship. Since the 1930s, the classic verdict of the West has been that Stalinist art, Social Realism, is not art but merely propaganda and therefore kitsch. I thought it was important to take this art seriously as art, and to examine exactly where – within these programmes ordered from on high — the small expressions of freedom can be identified, the places where a picture can say more than a thousand words. And also to identify where artists begin to articulate their scepticism about the world view of their leaders.

Exhibition

The show ‘The revolution is dead. Long live the revolution’ at the Zentrum Paul Klee and Bern’s Kunstmuseum coincides with the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. It runs until July 9.

Larissa M. Bieler: In Russia at that time there were heated debates about the social and political meaning of the arts. The Russian avant-garde was very interdisciplinary and wanted to penetrate all areas of life.

Kathleen Bühler: The artists of the avant-garde were mostly ready from the start to get involved in the revolutionary upheaval of society. They all wanted to contribute to social change and the emergence of a new human being, a new life and a new environment.

Larissa M. Bieler: Art has become very commercialised – in Switzerland too – we can see that the big fairs are detached from reality. And if art is political, it is not unusual for it to be punished by politicians.

Kathleen Bühler: Our capitalist system has promoted the art market and this is where fetishistic objects of desire are traded. But alongside that there is also art which can’t be sold, such as installations or works which intervene in social processes, and this is where the really important social questions are addressed. I think there is no art which is not political – even abstract art is political. Even an artist making apolitical art is acting politically by withholding comment. Any statement expressed in public is of a political nature. It is about announcing values and showing a world view, sharing it or even trying to influence someone with it.

Igor Petrov: How did the preparatory work with the Russian colleagues go?

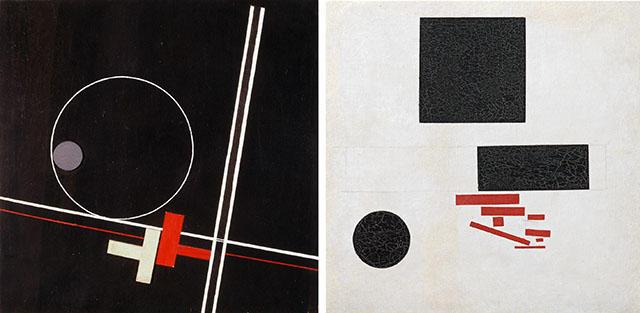

Kathleen Bühler: Choosing the works was a bit difficult because Russian art museums work differently. For example, online databases are unusual, so you can’t just browse through what is there. We had to fall back on what has already been shown in the West. Despite that, we are showing a fantastic selection of works by Alexander Deineka, for example. Deineka has never before been exhibited in Switzerland, at least not on this scale and not works of this quality. We have a wonderful selection of Malevich works. We are showing the abstract works in the Paul Klee Centre and the later, more figurative part of his oeuvre in the Bern Museum of Fine Arts.

Igor Petrov: What do you want to tell the world with this exhibition?

Kathleen Bühler: I wanted us to look again at this relationship between abstract and realist art, which has not been contradicted in the West for 100 years. But also to question this view that Socialist Realism was just propaganda and not art. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many artists from the former Soviet republics arrived on the international art scene, and rightfully expected their past work to be taken seriously.

Igor Petrov: When I first saw the poster for the exhibition I found it jarring. The Russian Revolution was an immense historical and human tragedy. Alongside the short renaissance of the Russian avant-garde, repression, mass executions and deportations took place. The best Russian artists and intellectuals were simply transported abroad on the so-called “philosophy ships.” This may be an art exhibition, but you can’t omit the historical context. What are you doing to illustrate critically the historical perspective of this art, so that people who come to the museum don’t get the impression that the revolution was a jolly walk in the park?

Kathleen Bühler: Your point applies to all the exhibitions taking place this year. It is clear that we have to counter any naivety. We chose this image because it also poses the question to the younger generation: Are you ready for a revolution? Or is it enough for you that you can enjoy your leisure time?

We wanted to show that revolutions are basically an uprising of the younger generation against the establishment, against those who have already found their place in society. For me, this was a first opportunity to spend a lot of time learning about the history of the Soviet Union. Much of this has still not been addressed in Russia. So our starting-point is the artistic angle, but it is always an opportunity to talk about the historical background.

Igor Petrov: It’s good that you mention this issue – the question of the youth and the question of whether the youth is ready for a revolution. Last weekend (26.03.2017) in Moscow, we witnessed the youth – those born around the year 2000 who have never known anything other than the current political regime – suddenly rebelling and taking to the streets. My question is, though: Were there any politically-tinged conditions for receiving loans from Russia? You said that all art is political – even neutrality is a political position.

Kathleen Bühler: There were no official limitations, but there were moments in which we were made to understand that we had to treat these works with all seriousness and care. I wanted, for example, to show a funny, obscene cacography of a collective farm harvest by the artists Alexander Vinogradov and Vladimir Dubbossarsky that I saw three years ago in Moscow. It is a harmless, exuberant exaggeration of a familiar artistic formula that we have known since the 1940s, and I would have very much liked to show this enormous picture – it is about 3 metres by 4 metres. It was produced in the 1990s, at a time when new freedoms were being tested, and it is associated with a certain kitsch, with a yearning for glamour. But we then realised that our other lenders didn’t find this joke funny. So we had to choose other paintings by these two provocative artists. The harvest scene is only illustrated in the catalogue.

Larissa M. Bieler: I would like to go back to the year 1915. You mentioned Malevich’s Black Square, an icon of art history. You have also mentioned the unique range of works in this exhibition. What in your view is the key work — if you had to choose one — and why?

Kathleen Bühler: One of the key works for me is by the multimedia artist Yael Bartana, an Israeli artist who filmed a trilogy from 2007 to 2011 with the title “And Europe will be stunned.” It was a work commissioned for the Polish pavilion at the Venice Biennale. In three parts, it is a thought experiment in which someone in Poland calls the Jews back to Poland. They come and build a town and at the end, the man who called them back is killed and mourned. Bartana sees this thought experiment through; she shows how things go wrong again and she uses the film language of the Russian Revolution. She uses the same dynamic camera angles; a view from below of the young hopeful faces to visualise the hopes that are tied to the dawning of a revolution. This trilogy makes an extremely strong impression and is very gripping. Although we know that the language of the film is connected to this historic tragedy, we are electrified and start to suspect towards the end that we are once more falling victim to the same deceptions. An artwork that can spark such powerful emotions but simultaneously inspire such terror is really brilliant. In my opinion it is an important task for today’s artists to continue to work on our consciousnesses.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.