‘The science of smell is simply amazing’

A biotechnologist from Silicon Valley heads research at one of Switzerland’s leading fragrance companies. Her mission: to use science to bring a sense of calm to as many people as possible.

Smells accompany every moment of our lives. They imprint people and places in our memory. They make our mouths water or provoke disgust. They make the experiences we have magical or terrible.

It was the ancient Egyptians who started to mix flowers, plants and oils into fragrances to wear on their body and hair or use as medicines and religious offerings. A woman named Tapputi, who lived in Mesopotamia around 1200BC, was the first chemist known to have used the technique of distillation to make perfumes.

Today, her legacy is in the hands of multinational fragrance and food technology companies, making billions of dollars every year. At the helm of some of these businesses is a new generation of female scientists who use biotechnology and artificial intelligence to produce complex fragrances and flavourings.

Sarah Reisinger is one of them. As a biotechnologist heading the research unit at Firmenich in Geneva, she feels the weight of a company legacy that includes Nobel Prize winners in chemistry (such as Leopold Ruzicka) and distinguished female scientists like Geneviève Berger, who directed the CNRS, the largest research centre in Europe.

Reisinger took over from Berger in 2021, when Firmenich had already brought laundry fragrances and meat flavourings to market with the help of artificial intelligence. Now Reisinger wants to harness algorithms and machine learning to develop innovative fragrances more efficiently.

“This means rethinking how we do science every day, from experiments to automation processes,” she says. Data science, she explains, can help design new fragrances through the analysis of thousands of formulas and raw materials. It can also make real-time analyses of chemical reactions and improve operations planning.

From Silicon Valley to Geneva

Reisinger greets me with a firm handshake and steady voice. Her white polka dot skirt brings a little cheer to the classic blue business suit. Unlike other managers I have interviewed, Reisinger does not seem particularly comfortable talking about herself and her achievements.

To break the ice, I ask about her upbringing. Reisinger is 45 and grew up in Minnesota in the United States. After school she moved to California, where she earned a doctorate in microbiology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Early in her career Reisinger worked on biotechnology to develop new drugs, especially for cancer treatment, and biofuels. She then moved on to research into ingredients and technologies for cosmetics and other consumer products.

Until the offer from Firmenich came in 2018 and the big decision to move to Switzerland. Reisinger has no regrets, but her husband and two children, aged five and ten, who followed her on this adventure, initially struggled with the language barrier and rebuilding a life.

Today Reisinger and her family feel at home in Switzerland. “We still lack bookshops and libraries in English though,” she says, hinting at a smile. She turns to reading as an escape from professional and family commitments.

Sometimes she thinks back fondly on her time in San Francisco, where she lived for 20 years, and recalls her passionate and highly motivated colleagues. “For most of my career I worked in Silicon Valley environments where passion was everything. I learnt a lot.”

But Reisinger doesn’t miss the pressure she felt while working for fast-growing start-ups, including pressure to return to work quickly after having her children.

Personalised scents

When we start talking about the science behind perfumes, Reisinger grows much more relaxed.

“The science of smell is simply amazing,” she says, explaining that we have more than 400 olfactory receptors in our noses, which often have small genetic differences from person to person. This means that people do not perceive smells in the same way. Reisinger is not only interested in understanding the human sense of smell, but also “the mechanisms of such a personal experience, about which we still know very little”.

Amid these personal differences, the challenge for biotechnologists like Reisinger is to create scents and aromas that bring positive emotions to as many people as possible. Scents are like chemical messages that are interpreted by our nervous system, generating sensations and emotional states. “When we smell a scent, something happens in our brain. But it is more than just a pleasant or unpleasant feeling,” she says.

Scents help us feel more comfortable and confident in certain environments. Sometimes, they can even influence the way we interact and react to certain situations A pilot studyExternal link showed that essential oils, especially sandalwood oil, can alleviate stress and facilitate recovery after a stressful event by reducing systolic blood pressure and salivary cortisol levels, which are considered biomarkers of stress.

In 2020 Firmenich launched a fragrance inspired by Mysore sandalwood oil, which is usually obtained from an endangered Indian plant. Reisinger’s team created their own sandalwood molecules, using DNA sequencing to identify and reproduce the enzymes responsible for forming the sandalwood odour. “By applying scent technology to olfactory receptor biology, we try to help people combat stress, unplug and find mental well-being,” Reisinger says.

Secretive industry

People’s sense of taste can be influenced, too. Reisinger tells me that her team is experimenting with new flavours to add to vegetarian or vegan foods that imitate meat. Smell and taste are closely linked, so much so that many people suffering from anosmia, a condition where the ability to detect smells is temporarily or permanently lost, also believe they have lost their sense of taste. (Anosmia cases skyrocketed during the Covid-19 pandemic, as the virus can cause loss of smell.)

“We are deepening our understanding of how our taste and smell receptors work and what activates them,” Reisinger says. For example, her team wants plant-based burgers to give off the typical fatty aroma of meat only during cooking and not when raw, to reproduce the sensory experience of the original products as closely as possible.

In May 2022 Firmenich announced it would merge with leading Dutch food company DSMExternal link. The announcement raised fears for the company’s future in Switzerland. In October Firmenich inaugurated a new 225,000m² production and research technology campusExternal link in Geneva, which cost CHF200 million ($203 million), to reaffirm the Geneva-based company’s close ties to the city.

Sarah Reisinger could have pursued a career in academia, sharing the results of her research for the advancement of science. Instead, she opted to work in the private sector, a move she says allows her to work on end products and influence the world in more tangible ways. Firmenich’s fragrances and flavourings reach over four billion consumers a day through products from perfumes and shampoos to breakfast cereals.

Reisinger says with a gleeful expression that her pride goes through the roof when she walks into a shop and sees all the perfumes containing fragrances developed by her team. She imagines people wearing them and feeling a moment of calm. “After all, it is from relaxation that true innovation is born.”

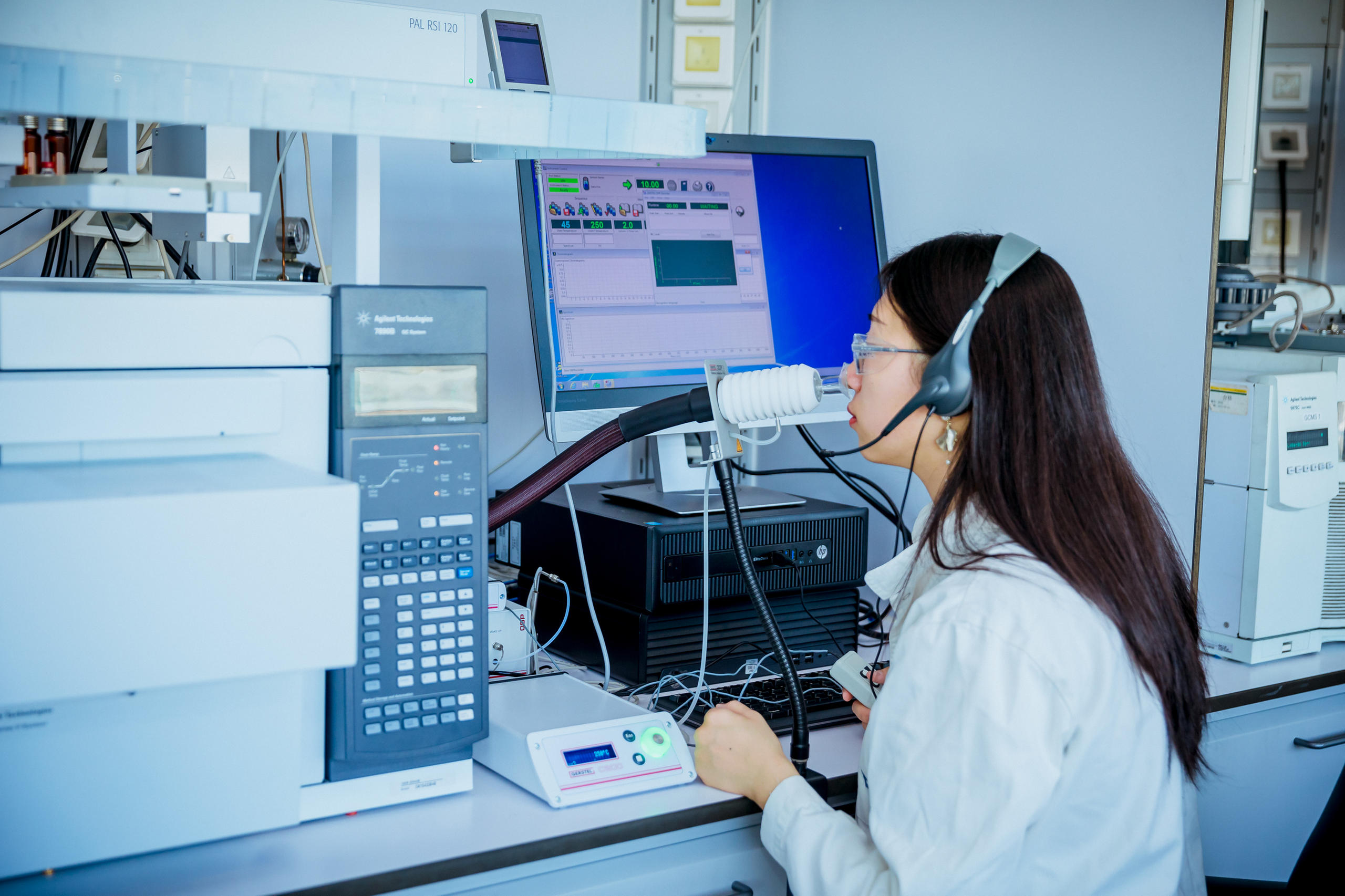

But how they might achieve this remains a trade secret. The perfume and fragrance industry is notoriously secretive: I am not allowed to visit the Firmenich laboratories or go into too much detail about certain technologies. Their communications manager sits in the interview, silently, but ready to step in for a tricky question.

Competition in the industry is fierce – especially between Firmenich and another Swiss-based fragrance firm, Givaudan – and Reisinger’s company, which has more than 10,000 employees worldwide, doesn’t want to give anything away.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.