Torrid time predicted for Switzerland by 2060

Over 40°C in the cities, long periods of drought and little snow in winter: in forty years’ time, Switzerland might look like one of the Mediterranean countries today. What effect would this have on society, tourism in the Alps, and the environment?

“Today the mercury hit 45 degrees in Geneva. The Swiss Plateau and the Alpine valleys had their twentieth day of tropical weather since the year started. The heatwave gripping the south side of the Alps and Valais for the past month will continue on into the coming weeks. Due to the ongoing drought, people are being asked to keep water consumption to a minimum.”

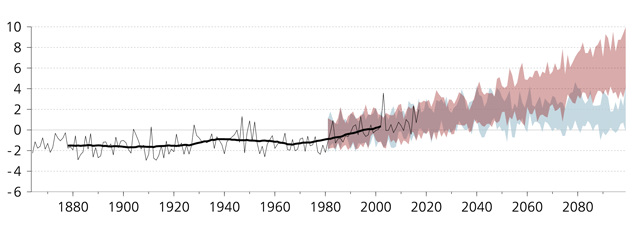

By the year 2060, it could be the typical national weather forecast on a summer’s day. This is based on new climate scenarios for Switzerland devised by MeteoSwiss, the federal department of meteorology and climatology, and the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ), published in mid-November. “Switzerland will be a hotter and a drier place,” summarised Peter Binder, the head of MeteoSwiss.

To get an idea of the kind of climate likely in Switzerland in the second half of the current century, it is enough to look at what happened this year, says Christoph Schär, a climatologist at the Zurich-based institution. “The 2018 heatwave was a warning for the future. The extremes we are seeing at the present time could become the norm by 2060.”

From Alpine glaciers to life in the major cities, swissinfo.ch takes a look at the likely effects of global warming – assuming that appeals for a drastic reduction of emissions continue fall on deaf ears.

Since 1850 the 1,500 or so Swiss glaciers have lost 60% of their volume. In the hot summer of 2018 alone, the loss amounted to 2.5%. Because of rising temperatures and less snow in the springtime, smaller glaciers are doomed, says Matthias Huss, a glaciologist at ETH. According to the federal environment ministry, only the ones in the highest parts of the Bernese Alps and Valais will survive, such as the Aletsch glacier.

The shrinking mass of the ice, as well as having an adverse effect on the landscape and on the stability of mountainsides, will also have repercussions on the water supply system. Based on current knowledge from climate scenarios of 2011, Olivier Overney, who heads the Hydrology division of the federal environment ministry, says that “climate change will mean important changes to water resources at the local level.” The new climate scenarios need to be combined with the hydrological models to yield more precise data, he adds.

The retreat of the glaciers will make a major difference to Europe’s great rivers which rise in the Swiss Alps. According to predictions, the volume of the Rhone could be down 40% in the coming years.

In future there will still be winters with heavy snow. They will just happen less frequently. People who want to ski at the high-altitude ski resorts like Zermatt or St Moritz will have to expect 30-60% less snow cover than today. Ski resorts at around 1,500 metres will lose about 100 days of snow.

In Adelboden, at 1,350 metres, there will be less snow days than there are now in the capital city of Berne (542 metres), say forecasters from the Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research and the Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne.

For some time now, tourist resorts have been offering summer and autumn aimed at reducing their dependence on winter tourism, says Bruno Galliker, a spokesman for the industry association of ski-lift operators. In Switzerland, however, he is at pains to point out, winter sports are not on the way out. “In the coming decades it will still be possible to ski in Switzerland, especially using man-made snow. Switzerland has a competitive advantage over neighbouring countries, because the skiing areas are at higher altitudes.”

More

Skiing on preserved snow

According to Galliker, climate change could even have a silver lining for Alpine tourism. “Fascinating new landscapes will appear. The rising heat down in the valleys will drive people to go up the mountains to cool off in more pleasant temperatures”, he claims.

Global warming will cause existing vegetation zones to shift upwards by 500-700 metres, researchers believe. In the Alps, deciduous trees like oaks and maples will take the place of conifers. The spruce, the most important tree for the Swiss forest industry, is likely to disappear from the Swiss Plateau due to exposure to harmful organisms like the bark beetle.

According to the experts, it will be crucial to foster diversity of trees, because a natural forest with a high degree of biodiversity is better able to resist hot summers and rainy winters. Here you can see how foresters are getting ready for the forest of the future.

Marco Conedera, a forest engineer with the Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape ResearchExternal link, warns that “rising temperatures, and less snow lower down, will add to the risk of forest fires”. In particular, it could mean that fires started by lightning strikes could become more frequent and more dangerous. These are hard to get under control because they affect mountain conifers in out-of-the way areas. “Another tendency we see happening already is high-risk fire season lasting into autumn and winter too”, explains Conedera.

Biodiversity in Switzerland is in poor shape at the moment, with 36% of all animal, plant and mushroom species on the endangered list, points out Urs Tester of the Pro Natura organisation. With global warming, the situation is only going to get worse. “Species from southern Europe are already making headway In Switzerland. But the number of native species about to be lost is huge. Natural habitats are deteriorating and the species are not finding any viable alternative. The hardest hit are the species that live beside waterways and lakes, in humid zones and the Alps, like the rock ptarmigan.”

Less rain in the summer months is not the only bad news for farmers. Increasing temperatures will mean quicker evaporation. As a result, the ground will get dryer and more irrigation will be needed. And not just that. Harmful pests are on the increase, and species and diseases from tropical and subtropical zones could get a foothold in Switzerland, points out Pierluigi Calanca of Agroscope, the federal institute for research into agriculture.

Farmers will just have to expect a lot more extreme weather like drought and flooding, which “will mean smaller harvests”, notes Sandra Helfenstein, spokesperson for the Swiss Farmers’ Union.

Global warming will have a favourable effect on some farming activities, however. “In future, it should be possible to grow rice on the north side of the Alps,” Helfenstein believes.

Switzerland produces 60% of its electricity with hydro power. Shrinking glaciers will have little impact on hydro-electric production, according to a recent study by the Swiss National Science Foundation. But long periods of drought might have a major impact: this summer, the power station at Schaffhausen, near the Rhine Falls, experienced a 50% drop in production.

Climate change will have a limited negative effect on hydro-electric production, says Felix Nipkow, who heads the “electricity and renewable energies” department of the Swiss Energy Foundation. “It is still possible that new lakes will form after glaciers shrink, to provide new opportunities to exploit hydro power,” he believes.

In 2060 winters will be milder, and heating needs will be less. This reduction will be more than made up for, however, by soaring power consumption during the summer for air-conditioners. The main challenge for Switzerland is giving up nuclear power bit by bit; at the moment it provides some 30% of our electricity.

To make up for the loss of atomic power, Switzerland intends to promote renewable energy, bring down levels of consumption, and improve energy efficiency. “Switzerland will have to focus on solar power, which is now the cheapest technology for production of electricity. It has the potential to produce double the power produced by nuclear plants today”, says Nipkow.

Because the ground is closed up and heat is being produced by traffic, industries and buildings, temperatures in the city are a few degrees higher than in the hinterland; in the case of Zurich, differences of over 4°C have been measured. Warmer summers are likely to turn cities into veritable hothouses.

To tackle this problem, cities will need more green and open spaces, exercise control over the colour and the thermic properties of buildings and improve air circulation – for example by setting limits for building height and density. The federal government is sponsoring projects on adapting to climate change, including one in Sion, canton Valais – the Swiss city that has warmed up the most.

More

The climatic metamorphosis of a city

Heatwaves are a major threat for Switzerland, says the federal health ministry. Most vulnerable are the elderly and infirm. During the long hot summer of 2003, prolonged temperatures of over 30°C caused about 1,000 premature deaths in Switzerland, and 70,000 in Europe.

Higher temperatures also favour the spread of infectious diseases previously confined to the tropics. In Switzerland there is concern about the spread of the Asiatic tiger mosquito, which could become a carrier of dengue fever or chikungunya. Hot summers also favour the spread of ticks, which are liable to be carrying meningitis and Lyme disease. The map below shows the current high-risk areas.

This may all seem like a doomsday scenario. But whereas global emissions are still rising, it is still possible to reverse the trend and avoid the worst eventualities, say the UN’s climate experts.

Reto Knutti, a climate researcher at ETHZ, emphasises that a concerted effort would pay off. “With a coherent plan to protect our climate, the effects of climate change in Switzerland could be halved by the middle of the present century,” he believes.

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee, swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.