‘Forgotten’ Swiss resistance fighters could be rehabilitated

More than 460 Swiss citizens fought in the French Resistance during the Second World War, but many were sent to prison upon their return for having done military service abroad. Rehabilitation could come in the form of a parliamentary initiative.

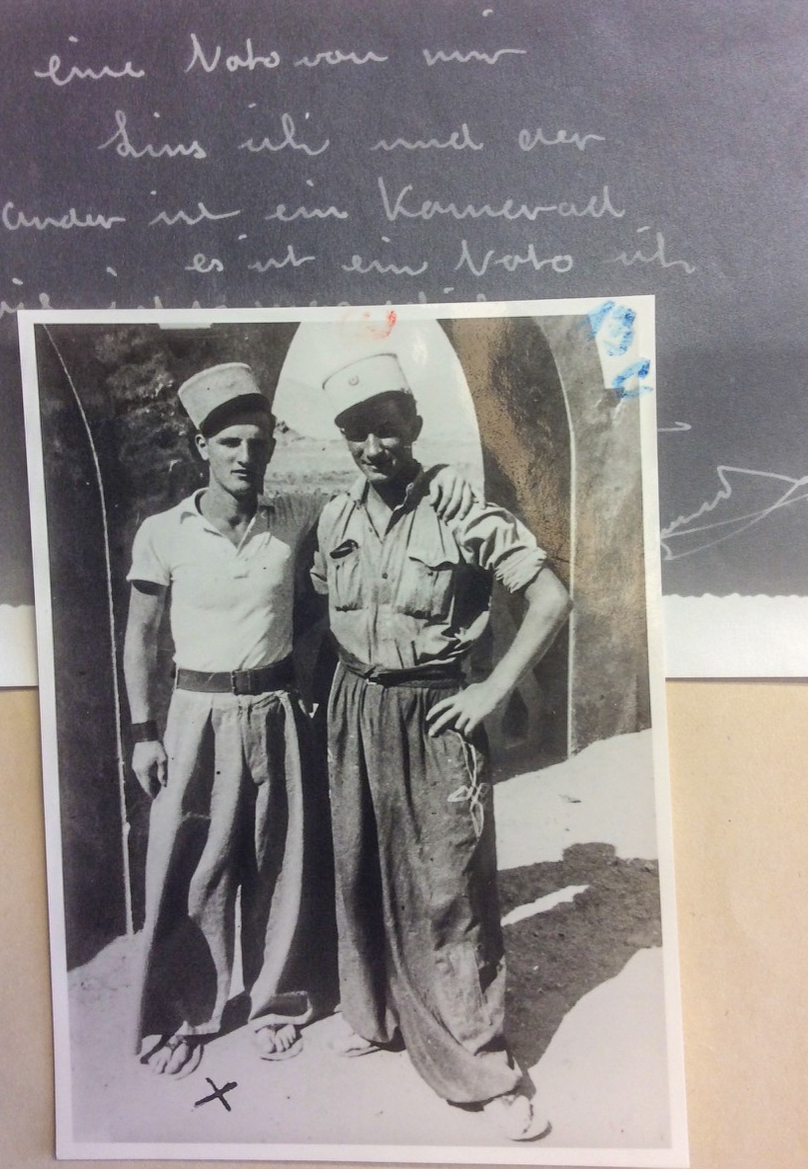

Paul Aschwanden, born in Schwyz in 1922, was the youngest of five children. His parents separated when he was two, and his mother placed him in an orphanage. After finishing school, Paul had trouble settling into a job. trying his hand as a painting apprentice, before working as a day labourer, factory hand, and a delivery man.

In 1940, shortly before the German offensive on the Western Front, he crossed the French-Swiss border in Basel and joined the French Foreign Legion in Mulhouse. He was just 18.

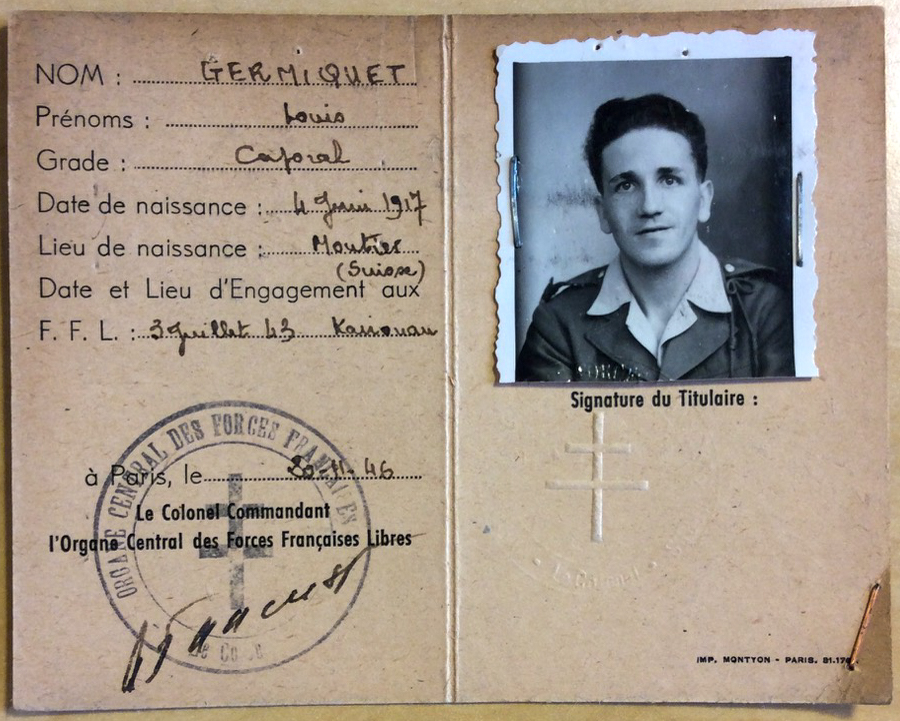

After six months basic training in Algeria, he had to decide whether to go and fight British troops in the Middle East or to build roads in the Sahara. Paul chose the second of these. In March 1943, however, after the American landings in Morocco and Algeria, he and other ex-legionnaires switched to the Allied side and joined the Free French forces of General De Gaulle.

Paul took part in the Italian campaign, and in August 1944 he landed in Provence. He won the Croix de Guerre French military decoration and was made an non-commissioned officer. But when he returned to Switzerland in September 1945, he was given a four-month suspended prison sentence.

Like Aschwanden, most Swiss citizens who fought in the French Resistance were former legionnaires recruited into de Gaulle’s Free French forces. Others were working in occupied France before getting involved with armed groups opposing the Nazis; half of them were dual citizens. In some cases, people left Switzerland to join the resistance group in France, the Forces françaises de l’Intérieur. Or they joined the Free French forces, which meant moving to London or places in Africa and the Middle East.

On returning to Switzerland, 200 of them were given jail terms, sometimes suspended. Others were dishonorably discharged from the army or lost their citizen’s rights. As a result, some stayed in France to avoid these penalties. Some, tried and sentenced in absentia in Switzerland, were actually killed in the fighting.

Who were the Swiss resistance fighters?

“They were not a homogeneous group,” says Swiss historian Peter Huber, author of a book In the Resistance. Swiss volunteers on the side of France. Published in 2020, it recounts the lives of Swiss fighters in the French Resistance, their military experiences, and what happened to them when they returned to Switzerland.

In most of the cases, the Swiss volunteers belonged to the working or lower middle classes. They were young, often from broken homes, and had found it hard to hold down a job. Many had criminal records for offences such as petty theft and vagrancy. But unlike the volunteers who went to fight in the Spanish Civil War, they rarely had any experience of political militancy.

Motivations varied: some, but not the majority, had anti-fascist leanings. Others, notably the Franco-Swiss dual citizens, acted out of patriotism. There were those fleeing difficulties in civilian life. And among the legionnaires, the decision to go over to the Resistance was sometimes a mere matter of survival. “In almost all their stories, though, you find a sense of disgust at the humiliation of France and Hitler’s megalomania,” says Huber.

Working towards rehabilitation

In 2006 there was a parliamentaryExternal link initiative proposing the rehabilitation of Swiss anti-fascist volunteers in Spain and Swiss fighters in the French Resistance. Three years after that, the Swiss parliament rehabilitated all who fought on the Republican side in Spain, but did not include those who had been in the French Resistance. This was due to a lack of information and historical research at the time, in particular on the motivations of the volunteers.

The publication of Peter Huber’s study in 2020 provided a scholarly basis for revisiting the issue. Two parallel parliamentaryExternal link initiatives, proposed by Geneva Ensemble à Gauche parliamentarian Stéfanie Prezioso and the Green Party’s Lisa Mazzone, have since called for formal rehabilitation, without compensation, of Swiss volunteers in the French Resistance. As in the case of Republican fighters in the Spanish Civil War, “the sentences passed at the time do not match current views of justice”, as the wording of the initiative put it.

Huber’s research reveals a diverse picture of Swiss volunteers’ motivations, with noble instincts often being accompanied by a kind of opportunism. So what justification is there for rehabilitation? “The Swiss fighters in the French Resistance, whatever their original motivation, contributed to the defeat of Nazism and the preservation of Switzerland,” Huber insists.

“At a time when we are seeing the rebirth of fascist-inspired views and a tacit desire to place Nazis and Resistance fighters on the same level, it is important to point out who was fighting on the right side,” adds Prezioso. “This is not a about honouring heroes, but rehabilitation is a way of reaffirming the democratic values that were being defended in the fight against Fascism, which are being called into question today.”

On October 29, the Legal Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives decided with a comfortable majority to support the parliamentary initiative. The Swiss French Resistance volunteers should therefore be on the way to receiving the same acknowledgement as the Spanish Civil War volunteers and those who helped refugees flee from Nazi persecution.

More

Swiss acknowledge wartime “heroes”

The unknown Resistance

Apart from the issue of rehabilitation, Peter Huber’s book deserves credit for drawing at least passing attention to the involvement of tens of thousands of non-French foreigners – among them 30,000 soldiers from French colonies in sub-Saharan Africa – in the liberation of France.

“After 1945 in France, this contribution was conveniently forgotten due to a ‘nationalisation’ of the Resistance in terms of ethnic identity,” the historian points out. “In Switzerland, on the other hand, the issue of volunteers in the French Resistance didn’t get any attention amid the whole mythology about General Guisan and the readiness of the Swiss army to defend the country.”

Huber’s book highlights other issues as well, such as the involvement of women in the French Resistance. “Women, not being required to do military service, could not be charged under the military penal code. Their names are therefore not found in military justice files, but consular service files,” he explains. “I think there must have been more Swiss volunteer women than the ones I found in my research.”

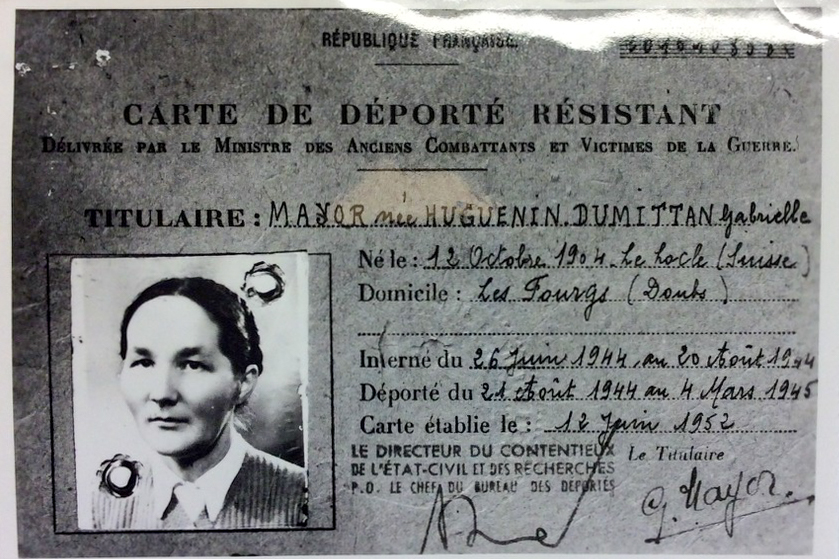

Born and raised in Le Locle, in canton Neuchâtel, Gabrielle Mayor married a dairyman with whom she settled in Dôle, on the French side of the Jura massif, in 1928. Two years after the occupation of France by German troops, the couple became involved with anti-fascist groups. Their farmhouse became the command post of a Resistance network: it had two radio transmitters, used by British intelligence agents.

In June 1944, following an Allied weapons drop, the network was uncovered. Mayor was arrested. Her brother immediately informed the Swiss consulate in Besançon. In September, she was deported to Germany, ending up in Ravensbrück concentration camp. It was only three months after her arrest that the Swiss embassy in Berlin asked the German authorities about her place of detention and the charges against her.

Mayor was liberated on February 4, 1945, and returned to Switzerland. She suffered serious health problems following her detention and for years she lived in considerable financial need. In 1959 she received her first financial grant for Swiss victims of Nazi Germany. However, the amount was initially lower than that requested, because Gabrielle Mayor, having been a “militant member of the Resistance”, was judged to be responsible for what had happened to her.

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!