The Swiss man who exposed exploitation of emigrants in 19th-century Brazil

Some 170 years ago, a Swiss citizen led a revolt in Brazil which exposed the exploitation of European immigrants to Latin America in the 19th century. The story sheds light on dilemmas still central to today’s debates on migration, forced labour and state responsibility.

Thomas Davatz left Switzerland for Brazil 170 years ago, in search of opportunity. Brazil, one of the world’s largest coffee producers, was coming under pressure from the United Kingdom, which had called into question a business model based on labour enslaved in Africa, approving laws such as the Aberdeen Act, which authorised the British Navy to capture Brazilian slave ships. In 1850, the transatlantic slave trade to Brazil was banned following this pressure.

It was in this context that the first initiatives emerged, led by Brazil, to attract Europeans to replace the dwindling plantation labour force. Brazilian landowners believed that bringing European immigrants to Brazil would lend the country an image of civilisation, while also whitening a population that had been profoundly shaped by enslaved Africans.

In the Alps, Davatz was a teacher at a rural school and was regarded as a highly respected figure in Prättigau, canton Graubünden, where he lived and worked. He had received an intense religious education shaped by the Inner Mission, a 19th-century Protestant movement widespread in Switzerland and other regions of Reformed Europe.

As an influential figure, Davatz led the arrival of one of the groups of emigrants contracted by a Brazilian company that acted as an intermediary between Brazilian landowners and Swiss workers.

“The idea was that, in order to civilise the Brazilian nation, it was necessary to bring Europeans here. There was both a whitening thesis and a civilising one, based on a misguided interpretation of Charles Darwin’s evolutionism, which was very influential in the 19th century,” says Victor Missiato, political analyst and history professor at Mackenzie Presbyterian University.

The Brazilian state therefore promoted immigration through official policies such as land grants, the hiring of recruiters in Europe and the dissemination of propaganda to attract workers. In 1848, the first German-speaking families arrived from various German states, including Switzerland. The group to which Davatz belonged reached Brazil in July 1855.

“These European peasants were, in a sense, resistant to industrialisation. They were people who bet on a rural solution to European crises, unlike many others who migrated to cities. They came with the expectation of becoming landowners, however small. That expectation was frustrated by the Brazilian project led by large landowners,” says Alberto Luis Schneider, who holds a PhD in history from the University of Campinas in Brazil.

In other cases, Europeans – and Swiss – in Brazil were not exploited but exploiting:

More

In the footsteps of Swiss settlers in Brazil and their slaves

From Prättigau to Limeira

“In August 1854 my thoughts turned to Brazil,” Davatz wrote in his memoir, Die Behandlung der Kolonisten in der Provinz St. Paulo in Brasilien (The Treatment of Colonists in the Province of São Paulo in Brazil).

“There my fine hopes would become reality, as numerous descriptions suggested through lectures, letters, printed materials and explanations of every kind. In this joyful expectation, I decided, as a member of the Poor Relief Commission, to submit a proposal to my municipality suggesting that it provide the necessary resources to citizens who wished to embark for Brazil without having the means to pay for the journey,” he wrote.

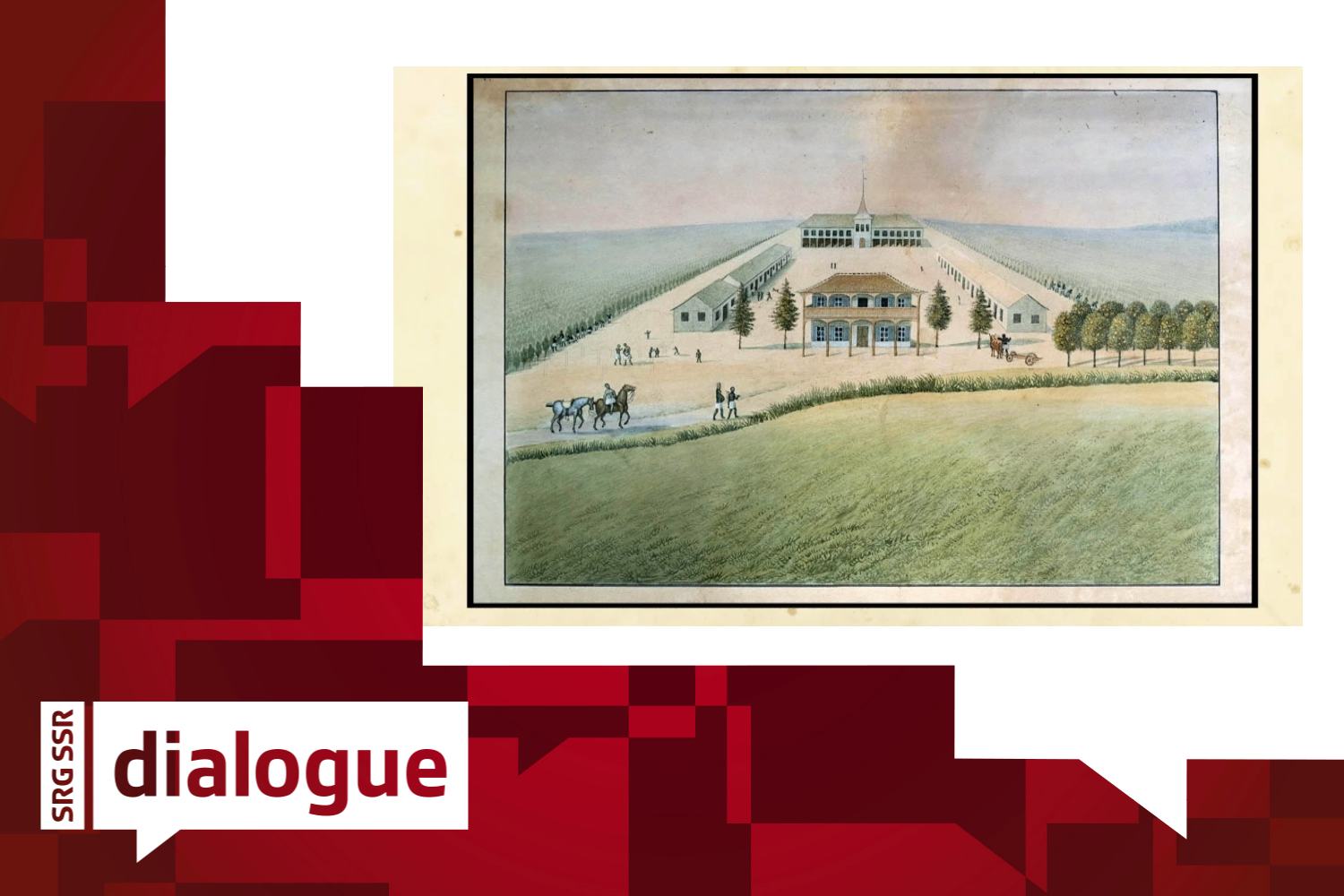

This leadership position also brought Davatz personal benefits. When he arrived in Brazil, he worked on the Ibicaba plantation in the town of Limeira, in the interior of São Paulo state, and took on an administrative role. According to Ilka Stern Cohen, co-author of the book Brazil Through the Eyes of Thomas Davatz, Davatz also had an official mission to send Switzerland a report on living and working conditions in the colony. This was intended to guide Swiss authorities on their emigration policy, which promoted emigration as a form of social welfare policy, aiming to improve the living conditions of its citizens at a time when the country was still largely rural and poor.

The revolt

After a year and a half on the plantation, where he worked as a teacher for the colonists’ children, Davatz demanded negotiations over the various problems he had identified among the colonists under the so-called partnership system. This model, adopted in 19th-century Brazil mainly on coffee plantations as a gradual alternative to slavery, granted emigrants a plot of land to cultivate and required them to share production with the landowner. It was presented as free and cooperative labour.

In practice, however, colonists were kept in a state of constant indebtedness. They were forced to purchase goods and services from the landowner himself, with accounts controlled unilaterally. The resulting debts restricted Swiss workers’ mobility and autonomy, turning the system into a form of labour that was formally free but marked by coercion and exploitation, comparable to slavery.

“Brazilian landowners came from a strong slaveholding tradition. They did not have a culture of dealing with free workers, and that certainly played a major role in the problems that emerged,” says Schneider.

According to Béatrice Ziegler, historian and professor at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland (FHNW), Davatz began to systematically monitor records of colonists’ expenses and income and to audit their account books. His work as a teacher and his literacy made him a natural leader among the Swiss colonists.

“In these analyses, he identified inflated food prices, fraud in the weighing of delivered coffee and irregularities in the prices paid for production, among other practices. Based on this evidence, he concluded that the colonists who were replacing enslaved people were being systematically deceived,” she says.

Although records do not point to widespread violence on either side, the confrontation was significant. Plantation owners who had until then relied on enslaved labour refused to accept any demands from free colonists. Fearing that the emigrants’ leader might be arrested or subjected to violence, as was common with enslaved people, in 1856 the colonists, led by Davatz, went to the plantation headquarters and threatened staff.

Read about Swiss-Latin American links during the Second World War below:

More

How Switzerland protected Latin American interests in Nazi Europe

Concern that the revolt might inspire enslaved Africans led plantation owners and local politicians to demand harsh measures against Davatz, who was accused of being a foreign agent and of damaging diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Swiss settlers lived alongside enslaved Africans on coffee plantations, sharing daily workspaces but occupying a legally distinct and hierarchically superior position within a system still structured around slavery, according to Victor Missiato.

Enslaved labour continued to be widely used, and although the transatlantic slave trade was officially banned in 1850, slavery itself remained fully legal in Brazil until its abolition in 1888, with illegal trafficking and an active internal slave trade persisting in the meantime.

That same year, Davatz left the plantation under the protection of other Swiss colonists and travelled to Santos, the main port of departure from Brazil at the time. From there, he returned to Europe by sea, with informal support from compatriots and under surveillance by the Brazilian authorities, but without having been arrested or officially deported.

Back in Switzerland, and into history

Back in Switzerland, in an effort to curb Swiss emigration Davatz published a detailed account denouncing the system of exploitation to which European immigrants were subjected on Brazilian coffee plantations. It was this written testimony, rather than any judicial punishment in Brazil, that turned his experience into a case of international resonance.

“Thomas Davatz’s account was not merely another picturesque description of Brazil one expected from a foreigner. It addressed sensitive issues such as oppression, abuses of power and the reactions of the oppressed, topics that were certainly uncomfortable and largely unknown to the national reading public,” says Cohen, co-author of the book Brazil Through the Eyes of Thomas Davatz.

The impact was immediate. “The effects began in Graubünden. The government was awaiting Davatz’s report because it intended to allow many more people to emigrate. When the report arrived, it not only had to abandon that idea but also feared protests from emigrants’ families, the press and political circles. Moreover, many municipalities, despite being very poor, had advanced funds for emigration and feared that colonists would never repay them,” Béatrice Ziegler explains.

Other German-speaking regions were also influenced by Davatz’s account. Shortly after the uprising, and alongside reports from other emigrants such as Theodor Heusser and Jean-Jacques Tschudi, an intense campaign emerged in Prussia, which discouraged German-speaking emigrants from moving to Brazil. Emigration to Brazil was officially banned in Prussia in 1859.

According to Ziegler, in Switzerland, although emigration remained a cantonal responsibility, emigration agencies in some cantons soon came under stricter control. In 1888, a national law entered into force that more clearly regulated the emigration process, reinforcing the idea that the state bore direct responsibility for protecting its citizens abroad.

In Brazil, the legacies of that period remain visible. In 2024, the Ministry of Labour and Employment reported the rescue of 2004 workers from conditions analogous to slavery, highlighting the persistence of exploitative labour relations.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.