Claudia Andujar – from war trauma to defending Amazon communities

The Swiss photographer, who turns 94 on June 12, has built an exemplary career in defence of Brazil's indigenous peoples. The Inhotim museum in Brazil is celebrating her life and work with an exhibition dedicated to indigenous Latin American artists who carry her torch.

When she arrived in Brazil in 1955, Claudia Andujar spoke Hungarian, French, German and English, but no Portuguese. Half a century later, in her book The Vulnerability of Being, which synthetises 50 years of her work, Andujar stated that her biography could only be told “through images” – and that photography was the language she had adopted “to communicate with the world”.

Today, at the age of 94, Andujar is an internationally recognised artist. She is also one of the most important voices in defence of the rights of the Yanomami peoples, one of the largest remaining indigenous groups in South America, residing along the border between Venezuela and Brazil.

In 2015, the Inhotim Museum, located in the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil, dedicated a an entire building to her called the Claudia Andujar Gallery. The space was then entirely conceived by the artist: “the work, the selection, the narrative, the assembly, everything came from her”, recalls Rodrigo Moura, then curator of the pavilion and now artistic director of the Museum of Latin American Art in Buenos Aires (Malba).

This original pavilion was the result of five years of research into the artist’s collection, aimed at presenting the scope of Andujar’s work with the Yanomami peoples, which goes much beyond photography, having acquired a larger political dimension.

Andujar divided the space into three large areas to present the 430 photos of the permanent exhibition: Land and Nature; The Human Being, which includes rituals, hunting, bodily expressions; and a third section called The Conflict.

This last section covers the impact of the contact between the “civilised” white man and the so-called “savages” as perceived by the “invaders”, namely loggers, smugglers and gold diggers. The illegal gold digging in the Yanomami lands is crudely exposed in her images, the first ones to raise an alert to the environmental and social degradation caused by the illegal trampling of the Yanomami territory.

Maxita Yano: multiple perspectives

This year, to celebrate its tenth anniversary, the Claudia Andujar Gallery has been revamped with a show of 90 photographic and audiovisual works by 22 indigenous artists from South America.

The space has been renamed Maxita Yano, which means “earth house” in the Yanomami language. The goal, according to curator Beatriz Lemos, is to bring complexity to the debate on visual representation of indigenous peoples, without forgetting that Andujar “is a forerunner, a great reference for many indigenous artists”.

Brazilian artist Denilson Baniwa, who has one of his works commissioned for the exhibition, also emphasises the importance of Andujar as a “fundamental ally” with a work that is “essential for more indigenous artists to be seen and respected inside and outside institutional spaces”.

For Bolivian artist Elvira Espejo, who also has works included in the pavilion and is the former director of the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz, Bolivia, the inclusion of indigenous artists is important because it presents two different perspectives. “The indigenous peoples are viewed from within and from outside, offering a larger diversity of readings”.

A painful youth

Andujar’s commitment to causes related to displacement, trauma and death is closely intertwined with her own biography, the stages of which come to light in the two documentaries dedicated to her, Gyuri (2022), by Brazilian director Mariana Lacerda, and The Lady of the Arrows (2024), by Swiss director Heidi Specogna.

In Specogna’s feature documentary, Andujar tells how her mother, Germaine Guye, who moved to Transylvania to teach French, insisted that her daughter be born in Switzerland, her country of origin, rather than in Oradea (now Romanian territory and at the time called Nagy Varad in Hungarian), where she was living with her husband. Thus “Claudine Haas” was born in Neuchâtel in 1931. After the parents’ divorce in 1938, she was separated from her mother and her childhood was spent close to her father’s Jewish family.

The Second World War uprooted her childhood. Claudine went back to live with her mother, who was not Jewish, and was sent to a Catholic boarding school, whilst her father’s family was sent to a ghetto after the German occupation of Transylvania. Staying with her mother at that time meant saving her own life, she says in her book.

The two women fled Hungary to Vienna through an Eastern Europe in turmoil, and after months on the road reached Switzerland in December 1944. Andujar still remembers “the cleanliness and the abundance of chocolates”, as told in The Vulnerability of Being.

>> Trailer of the documentary The Lady of the Arrows, by the Swiss film maker Heidi Specogna:

Forgetting Claudine

Her turbulent childhood and the fact that almost all of her family was killed by Germany’s Nazi regime “is something that doesn’t leave me to this day,” says Andujar in Specogna’s documentary. The years she grew up away from her mother established a distance that was difficult to bridge. “Claudia missed her paternal family, whom she had to leave behind, without knowing their fate,” the filmmaker told SWI swissinfo.ch.

Years later, mother and daughter would learn that the father and his entire family had been killed in Dachau concentration camp in Germany. The extermination of close relatives would haunt the artist into adulthood.

When she was 15, her uncle, the only survivor of her father’s family, invited her to stay with him in the United States. She then took the decision to leave everything behind to transform herself into a new person: “I wanted to forget Claudine for a while,” the artist confesses in The Lady of the Arrows. And so, Claudia was “born”.

At the age of 18, she married Julio Andujar, the son of refugees from the Spanish Civil War, from whom she would adopt the surname she still bears today.

The relationship was short-lived, but the fear of “being discovered as Jewish” made her keep the name. “I harboured this atavistic fear for a long time and avoided talking about my ancestry,” says the artist in an interview published in The Vulnerability of Being.

At home in Brazil

In 1955, at the age of 24, Claudia Andujar travelled to Brazil to visit her mother, who had moved there. As soon as she arrived in São Paulo, she felt “at home” and was initially “charmed by the kindness of the people”. She abandoned painting, to which she had devoted herself in New York, to become increasingly involved with photography.

In 1958, she made her first contact with indigenous peoples. In 1971, together with her then-partner, the American photographer George Love (1937-1995), Andujar went on a trip to the Amazon on behalf of Realidade, a Brazilian version of Life magazine that devoted an important part of its layout to photographs.

While Love took aerial images of the region, Andujar photographed on the ground, exposing the dire living conditions of indigenous communities. This was the first time the topic was highlighted so prominently Brazil’s media.

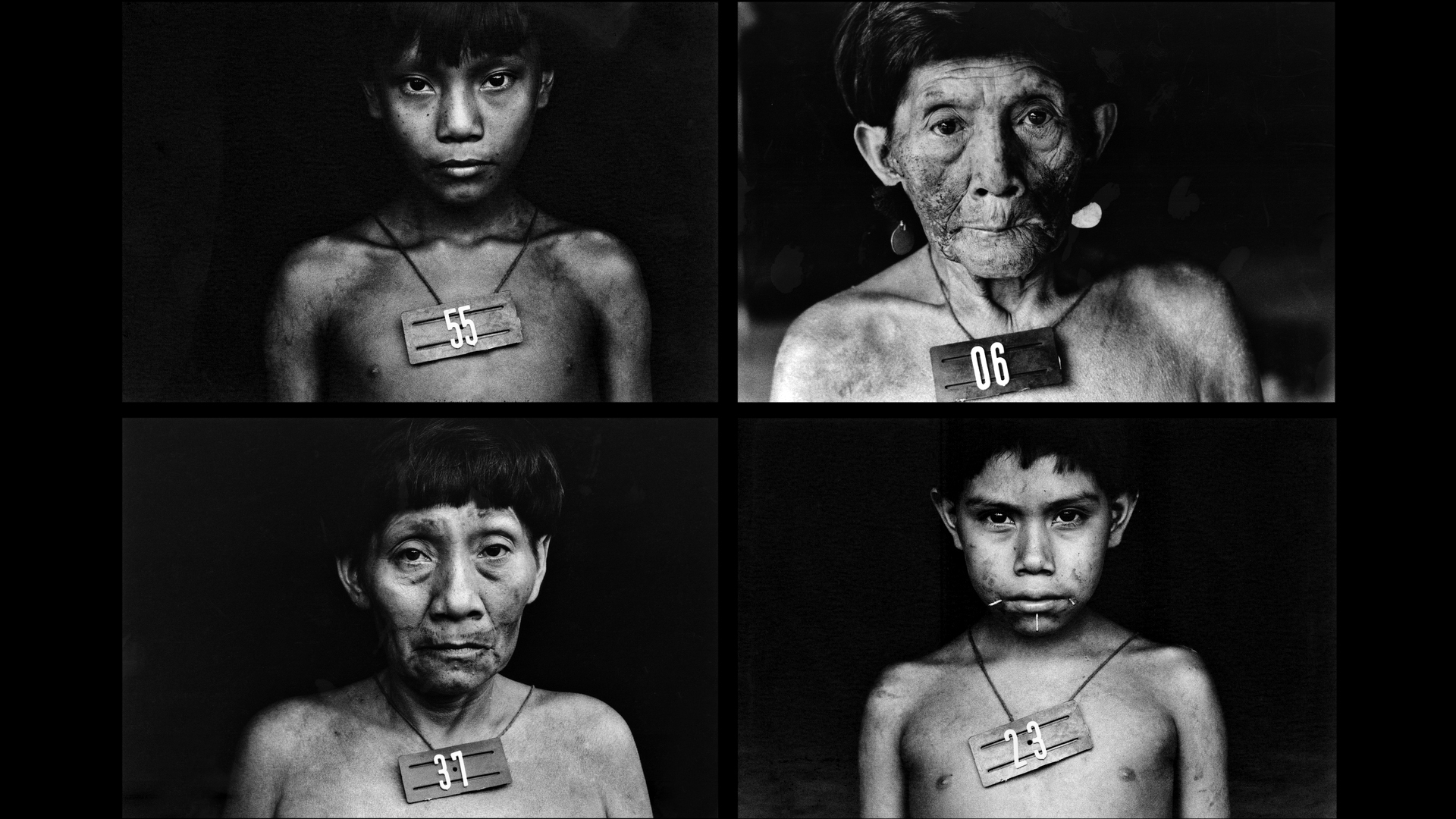

The Holocaust and the pain caused by loss in her own family would also serve as a reference point for one of the artist’s most poignant later works. Marcados (Marked), a series of photographs taken between 1981 and 1983, was the result of a trip made to survey the health of the Yanomami, with the aim of demarcating their territory.

Together with medical teams, Andujar registered each individual with a number which was hung around their necks. These would later be used for medical purposes and for their vaccination records. The series on show consists of 82 portraits accompanied by a report written by Andujar, describing the living conditions of the Yanomami.

The allusion to concentration camps, where numbers were used to discriminate peoples and later meant near certain death, was intentional. “In my family, the numbers tattooed on their skins were a sign of death. These ones were meant to save lives” reflects the artist in the documentary The Lady of the Arrows.

Edited by Virginie Mangin & Eduardo Simantob/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.