Data security issue causes concern over Swiss digital ID

Amid increasing use of digitalised commercial offers and electronic government services, Switzerland’s parliament approved a special law regarding digital identity. Through the ballot box, opponents want to veto it because of data security concerns.

Unlike many other European countries, Switzerland does not provide its residents with a certified verification method for a digital identity, also referred to as eID.

The law approved by parliament is aimed at simplifying the use of online services with a single login function. It has not yet been implemented due to questions raised by opponents.

At the centre of the debate is what role the state should play in such a technical and personal issue.

A law defining the principles for an eID, a system to ensure secure access to online services and to carry out electronic transactions, has been challenged to a nationwide vote over data security concerns.

Under the law, the Swiss government’s role is limited to making available the necessary data.

The legislation approved by parliament in 2019 leaves its mainly up to private companies (as well as cantonal or municipal authorities) to issue eIDs and act as so-called identity providers (IdP).

To prevent abuses, an independent panel has been set up to certify and oversee those private companies.

A digital ID for individuals allows users to simplify business transactions over the internet and facilitate contacts with the authorities. But it is not mandatory for citizens to hold an eID and the Swiss law states that there must be alternative technical options to phone applications, USB sticks or smartcards to verify the digital ID of online users.

Opponents’ main problem with the law is the right of private ID providers to issue digital identities and the risk that such data may be used for other purposes.

Critics of the new law argue the state – and not private companies – must be the gatekeeper of eIDs to guarantee its citizens the secure use of online services, be it for commercial or government uses.

They say it is a matter of trust and credibility for the state, especially because citizens could use the service to participate in politics, such as through e-voting and other government services.

Opponents have also warned that there is a danger of data abuse if private companies are given the right of issuing eIDs, despite assurances of strict security measures.

They refer to opinion polls which found that an overwhelming majority of respondents prefer the government to oversee eID data rather than industry providers.

For their part, supporters of the law have stressed the need for legal regulations in an increasingly digitalised world. They say the “Swiss model” of industry and the state sharing responsibility has proved successful in the past.

Examples from other countries have shown that centralised national systems are not suitable, according to supporters of the eID law.

They argue that private companies are better qualified for the role of providers, because they are more innovative and flexible than the state, which in its classic role sets the rules and oversees the activities.

Campaigners have stressed that Switzerland can’t afford to delay legal guidelines anymore and rejection of the law would seriously undermine the competitiveness of Swiss companies against multinationals.

An alliance of civil society groups supported mainly by left-wing parties and trade unions has challenged the new law adopted by parliament in 2019 to a nationwide vote, due to go before voters on March 7.

About 65,000 signatures were collected within three months and submitted to the authorities in January 2020. At least 50,000 signatures are required to force a referendum on existing legislation.

The right to veto a parliamentary decision is part of Switzerland’s system of direct democracy.

The referendum committee is made up of citizens’ rights groups and democracy activists. The left-wing Social Democrats and the Greens as well as centrist Liberal Greens are backing the challenge to the eID law.

Eight of the country’s 26 cantonal authorities do not recommend approval of the law, and therefore support the referendum.

However, in line with a majority of parliament, the main parties on the political right and the centre have come out in favour of the law.

The government as well as the main business groups – the Swiss Business Federation (economiesuisse) and the Association of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises – support the law.

When it comes to establishing a certified national eID system, Switzerland has fallen behind other European countries, which predominantly offer public-private solutions.

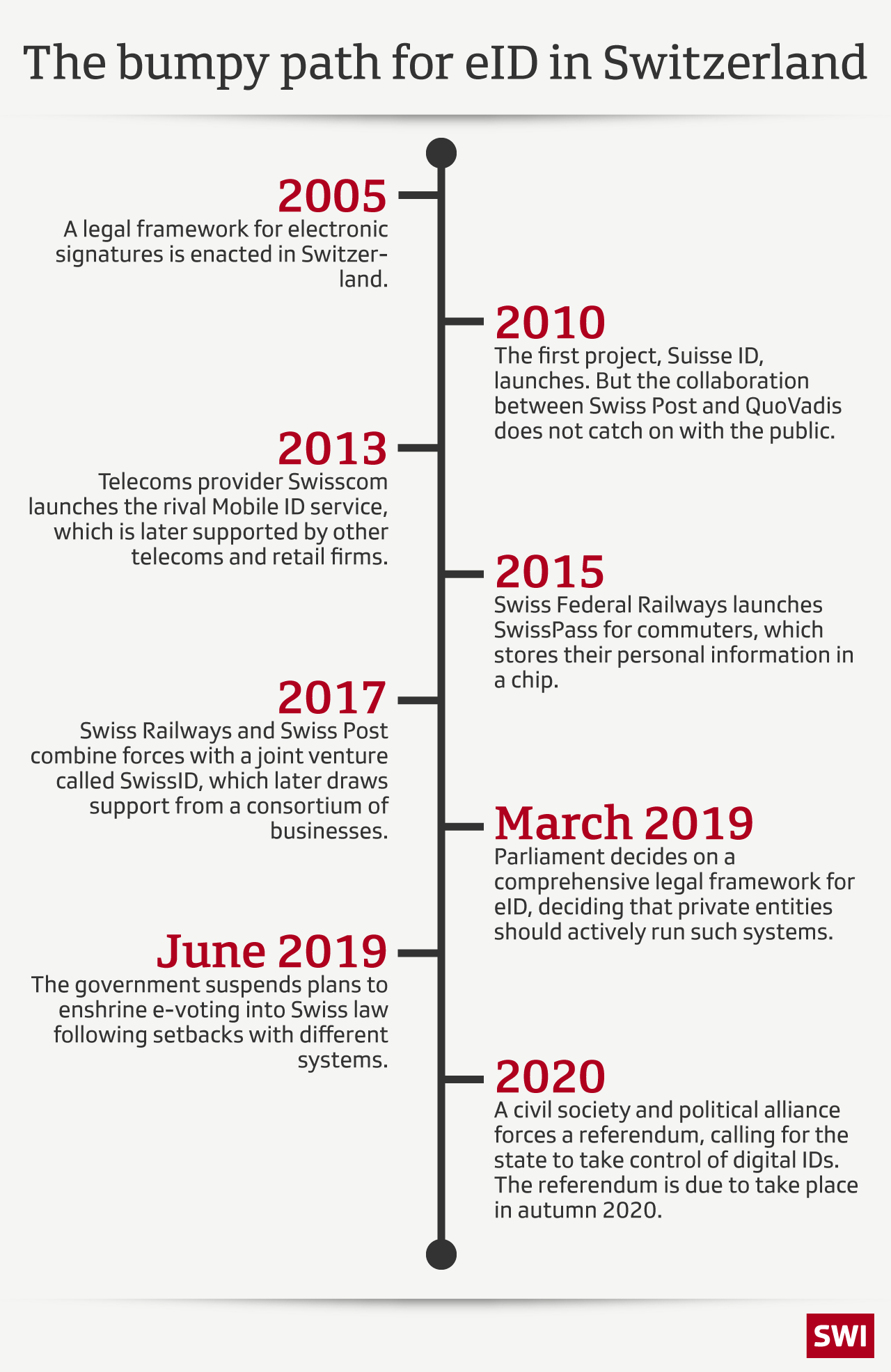

A previous attempt to set up a public-private e-identity solution, known as SuisseID, failed more than ten years ago. An improved project was launched in 2017.

Europe is a pioneer in this field, says Robert KrimmerExternal link, expert on e-governance at the University of Tartu in Estonia.

Elsewhere in the world, notably in the United States, private providers prevail over a government-run eID offering.

In 2016, the European Union adopted regulationsExternal link over the use and recognition of national e-IDs.

Estonia is at the forefront of digitalisation in this area. Some see Estonia’s approach as a possible model, but the Swiss government argues the situation in the Baltic state is too different to apply it to Switzerland.

Adrienne FichterExternal link, a Swiss political scientist and digitalisation expert, in 2019 compiled a list of European countries which rely on predominantly public eID providers (8), exclusively private providers (two) and countries with both public and private providers (13).

The digital ID is a cornerstone for additional applications, including e-signature or e-voting. But the creation of an eID doesn’t necessarily and automatically lead to such implementations,experts say.

An eID does not give someone the right to do something (like travelling or driving a car) but is purely an unambiguous means of identification comparable to a computer login user credential.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=a45b19f3)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.