Love letters and technology help restore pivotal Swiss film from ashes

A pioneering Swiss melodrama, shot in 1934 by an Estonian born in the Russian Empire who fled the Bolshevik Revolution, has won a new lease of life after meticulous restoration. Swissinfo met the restorers at a film festival in Bologna to talk about the kidnap drama Rapt – a commercial flop at the time of its release but now widely viewed as a milestone in Swiss cinema.

The courtyard of the Cine Lumière at the Cineteca di Bologna serves as a meeting place for film lovers, archivists, and critics all year round, but especially during Il Cinema Ritrovato, the legendary Italian festival of archival and restored film.

In the shade of a few trees and hammock-like overhead tarpaulins, festivalgoers gather between screenings to escape the scorching sun, imbibe gallons of water and garrulously pore over the day’s cinematic treasures.

In June, this courtyard was where Swissinfo met Caroline Fournier, head of heritage, and Julie le Gonidec, responsible for the digital lab at the Cinémathèque Suisse, and Camille Blot-Wellens, an independent researcher, to talk about their much-anticipated new restoration of a crucial film in Swiss cinema history playing at the festival: Dimitri Kirsanoff’s Rapt (1934).

Upon its release, Kirsanoff’s first and only Swiss film was acclaimed by some critics but flopped commercially, ensuring its obscurity for decades until its belated rediscovery in the 1970s and 1980s. Today it is admired for its bizarre mix of pastoral melodrama and outright surrealism, and continues to be listed among the most underrated works of the transition between silent cinema and early sound film.

Revenge for a dog

Rapt grapples directly with the contradictions of Swiss society before the war: the story centres on a man from an isolated French-speaking Catholic village in the Valais who kidnaps a woman from a German-speaking Protestant Bernese village to avenge – in one of the strangest of all plot impetuses – a slain dog.

“We didn’t want just a new, technologically perfect restoration,” Fournier tells Swissinfo the day before the screening.

“We wanted it to be a research project – really contextualising the film. That’s why we decided to work with Camille, who’s brings a lot of skill with that, in unearthing and investigating different versions, and the material history of the film.”

Among other things Blot-Wellens discovered is that Rapt is a purely Swiss production – not the French-Swiss production as it has long been described.

“So, it’s not just about making it look good; it’s about understanding what we’re restoring and why,” adds Fournier.

Pre-war, avantgarde cinema

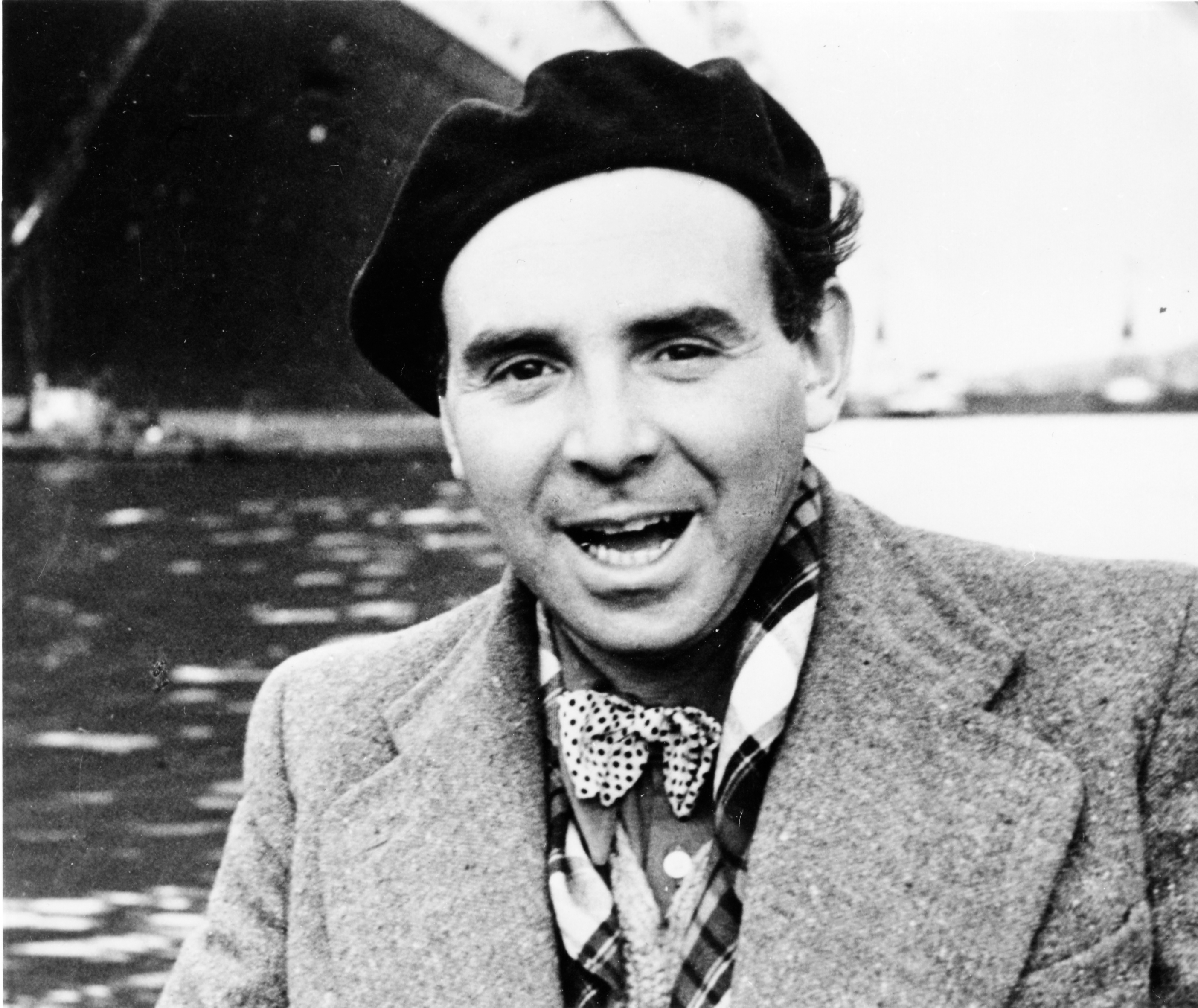

The fact that an Estonian avant-garde filmmaker like Kirsanoff, heavily identified with his work in France, directed this landmark of early sound cinema in Switzerland shows that cinema of the pre-war period was not as standardised within a rigid studio system as historical cliché would have us believe.

Born Marc David Sussmanovitch Kaplan, Kirsanoff adopted his artist’s name after moving to Paris in 1921 following his father’s murder by the Bolsheviks. He is most famous today for Ménilmontant (1926), a 37-minute avant-garde masterpiece without traditional intertitles that was the favourite movie of Pauline Kael, the influential, long-serving film critic of The New Yorker magazine.

But Rapt was also Kirsanoff’s last major work; during the Second World War he was forced to work in the fields in southern France in hiding as a Jew, and his career after that unhappy period turned to lesser commercial projects. It was also the first and only production by Mentor-Film, the pet project of the prominent Swiss playwright, novelist and journalist-turned-producer Stefan Markus.

The cast and crew were international and Swiss; “a real crossroad of the races, Switzerland,” reads the sardonic opening title card, adapted from Charles Ferdinand Ramuz’s 1922 novel The Separation of the Races.

A history of restoration

This is the third restoration of Rapt, which suggests some of its enduring significance and appeal. There was a restoration from a film print in 1978, and then from the original negative – much preferred in restorations – in 1995, which is the version seen most often at screenings and on home video since then.

“It’s quite common to repeat restorations because of technological change, and sometimes new materials appear, which happened [in the 1995 restoration],” Blot-Wellens says. “But this time, the fact that Caroline insisted so much on the need for intense research, on contacting other archives to see what they had, to really have a better idea of all aspects of the film – that made a big difference.”

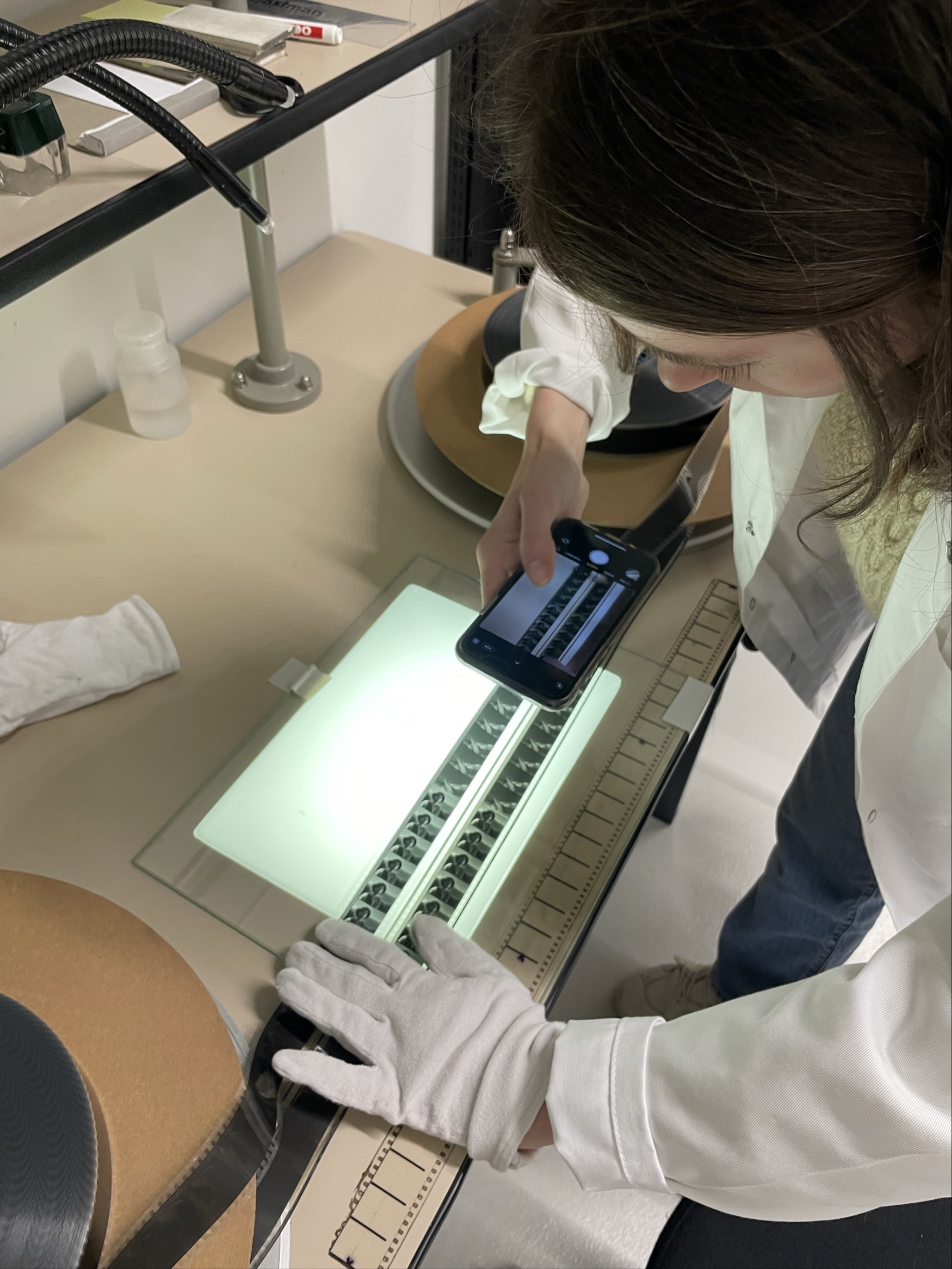

The restoration process was not straightforward. The French negative was incomplete, with decomposing reels and missing fragments. A German print featured different takes – original, but not identical, as was a common practice at the time, especially in Switzerland, where films were released simultaneously in French- and German-speaking markets.

The digital process of restoration involved careful decisions about what to keep and what to remove: “On one hand, we decided to remove as much of the dust and marks on the print as we could,” le Gonidec says. “But we also strived to keep all the specificities of the original material in there, as that’s also part of the character of the film.”

The alternative universe of the screen

On the day of the screening, the film is a thing of shimmering beauty, a rapturous restoration of a beguiling not-quite-classic that brims with outright surrealist images.

One wonders, watching the film, whether there’s an alternate universe where Kirsanoff might have had a career like Luis Buñuel, who rebounded from dire personal straits after the Second World War and was reborn first as a commercial director in Mexico, then as an arthouse darling in France and Spain.

Perhaps what most stands out in Rapt is the strikingly experimental soundtrack, with warbling, alien sounds accompanying some of the most ecstatic scenes in the film, such as the raging of a fire that consumes a house in the climactic sequence.

“The soundtrack itself was marked with ink [in the original negative], and from that we understood that when they were working on the material in the lab [in 1934], there was a fire and part of the original sound material was lost,” says le Gonidec. “They had to recreate the sound artificially, which Kirsanoff took to the extreme. So it was a very, very complex work to restore that in this restoration.”

“That’s why it’s really important to properly store the original material,” added Blot-Wellens. “It’s an aspect that is not so much commented upon. Without good storage, there is no restoration.”

She adds that they wouldn’t have had the same freedom to work so attentively without the original negative, “and the research – for example, using love letters between the two stars, helped us understand more of how, when, and in what manner the shoot happened,” she says.

“We wouldn’t have had the same freedom to work so attentively without the original negative, and the research – for example, using love letters between the two stars, helped us understand more of how, when, and in what manner the shoot happened,” le Gonidec reveals.

Kirsanoff’s film, like so many of those that were screened either in new digital restorations in Bologna, is alive today thanks to these efforts.

Alive in the sense that it still exists, that it can be shown in pristine condition in a 35mm print in front of an audience in 2025, now in Bologna and in the future in cinemas in Switzerland. And alive in the sense that it keeps evolving, that new research can influence and even shape our perception of it, and eventually push it into the arms of new audiences eager to discover it.

There is, in this sense, no cinema of the past, only an ever-evolving present. After all, this is only a restoration of the French-language version of Rapt; as the Cinémathèque team stress. Another restoration project will concentrate on the German version, which was shot simultaneously with most of the same cast. The work goes on.

Edited by Catherine Hickley/ac

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.