How a strike threat reshaped Swiss democracy

“Next stop: Olten.” The biggest rail junction in Switzerland was once also home to the Olten Action Committee, which in 1918 called the first nationwide strike – with far-reaching consequences for Swiss democracy.

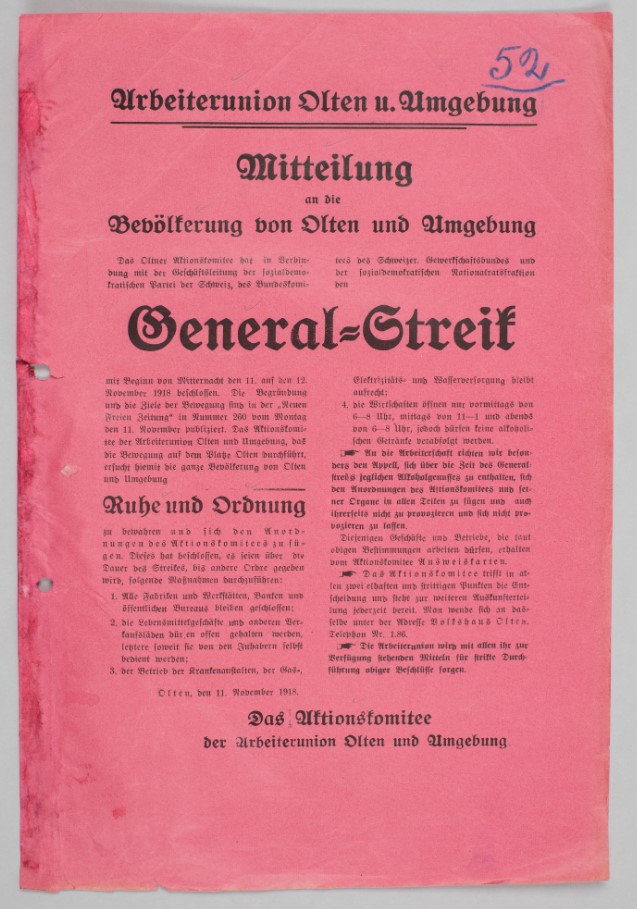

On November 11, 1918, the First World War came to an end with the fall of the German Empire. One day later, workers in Switzerland started a general strike. It was organised by the “Olten Action Committee”, which coordinated the nationwide protest from a building there called the House of the People.

Olten, some 50km west of Zurich, is Switzerland’s main rail junction, where train lines from north to south and east to west come together. For a long time the station buffet at Olten was jokingly regarded as the unofficial centre of Switzerland. So Olten was just the right place to be the centre of a national strike. From there, militant workers could send out their instructions to every part of the country.

This series in several parts is tailored for our author: Claude Longchamp’s expertise makes him the man who can bring alive the places where important things happened.

Longchamp was a founder of the research institute gfs.bern and is the most experienced political analyst in Switzerland. He is also a historian. Combining these disciplines, Longchamp has for many years given highly acclaimed historic tours of Bern and other sites.

“Longchamp performs democracy,” was one journalist’s headline on a report about a city tour.

This multimedia series, which the author is producing exclusively for SWI swissinfo.ch, doesn’t concentrate on cities – instead its focus is on important places.

He also posts regular contributions on FacebookExternal link, InstagramExternal link and TwitterExternal link.

In the French-speaking part of Switzerland the response to the strike call was muted; people were just glad the war was over. But starting in Zurich, German-speaking militants saw this as an opportunity for a real social revolution.

The strike committee made nine demands:

Calling of new elections based on proportional representation;

Votes for women;

A general obligation to work;

A 48-hour week;

A reform of the army;

Ensure availability of food supplies;

An old-age and disability insurance scheme;

State monopoly of foreign trade;

A wealth tax to reduce national debt.

The federal government reacted immediately by calling out the army. It also convened a joint session of the two chambers of parliament. Without responding to the demands, it issued an ultimatum for the strike to end. It was like a declaration of civil war.

On the morning of November 14, 1918, the Action Committee and the Social Democratic parliamentary group called off the general strike. They wanted to avoid further escalation and even bloodshed. There were dramatic scenes in the industrial town of Grenchen, however, where even after the official ending of the work stoppage, three young strikers were shot dead by soldiers.

The workers’ movement regarded its first direct extra-parliamentary action as a defeat. This had to do with how the nine demands were granted – or not.

What actually happened doesn’t take long to tell. The 48-hour week was quickly implemented, replacing the previous 59-hour week. Pension legislation took much longer; it came only in 1947. Women didn’t get the vote until 1971. And a wealth tax to bring down the national debt has never been tried in Switzerland to this day.

New electoral law redistributes power

Proportional representation was also introduced quickly – not by the government or even parliament, but by the people themselves. In the middle of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, the nation’s (male) voters accepted a people’s initiative to change the manner of electing representatives. The initiative passed with a 67% majority; a majority of cantons was also secured.

All of a sudden, power relations changed in Switzerland. The general strike was a catalyst here. The federal government, which had been using the excuse that the new electoral system was difficult to implement, had to yield. In August 1919 the nation’s voters decided on a dissolution of parliament and new elections. This was the first time this happened in Switzerland and has never happened since. The majority this time was 72%.

In these first nationwide elections under proportional representation in 1919, the Free Democratic Party lost 43 of its 103 seats in the House of Representatives. It was the worst defeat in the party’s history. This party of the well-to-do, which until then saw itself as the natural governing party, had to make room for new political formations. The smaller independent Liberal Party lost out too.

The big winner was the conservative Farmers’ Party (which later became the Swiss People’s Party). This party had emerged in 1917 in Zurich and Bern as a breakaway faction from the Free Democrats. It advanced from three to 30 seats. The left-wing Social Democratic Party, representing the workers’ movement, doubled its strength from 22 to 41 seats. That meant it now shared second place with the stable Conservative People’s Party (later the Christian Democrats, now the Centre party).

This development was not entirely fortuitous: 19th-century Switzerland was a patchwork of regions divided along language and religious lines, and these regions were well served by the first-past-the-post system. But when industrialisation came, there were new societal groupings that wanted a political voice. The workers’ movement was first, then farmers and small business. Proportional representation made room for them, and to this day it is regarded as a more just system.

Gradual overhaul of the federal cabinet

Historians agree that 1918 and 1919 were the biggest time of change in the political history of Switzerland. The dominance of the Free Democrats in the federal cabinet in particular needed to end.

That change happened bit by bit. The first step was in 1919, when the party had to give up two of its six seats, to a Conservative and a Liberal. This was only a stop-gap solution, though.

The next change came in 1928, when the seven cabinet seats went to four Free Democrats, two Conservatives, and one Farmers’ Party member. The third happened during the Second World War. To avoid a hardening of fronts like at the end of the First World War, the Social Democrats entered government in 1943 for the first time.

Though left-wingers and conservatives had got together to put an end to the Free Democrats domination in national politics, Social Democrats acquired their permanent membership in the federal cabinet only in 1959. This was the beginning of the Swiss “magic formula” for making consensus-type governments, with two each from the Free Democrats, the Conservatives and the Social Democrats, and one from the Farmers’ Party. It stayed that way until 2003. That was to be the longest stable phase in this system of government.

Competition to consensus

Political scientists regard this as representing the transition from the adversarial party-political democracy pioneered in the English-speaking countries to the Swiss idea of consensus democracy (see box).

The ideal of competitive democracy, usually with two parties that take turns at being government and opposition. Switzerland was like that in 1848, not least because elections to the two chambers of parliament were on a “first-past-the-post” or simple majority basis. But the needed alternation of parties in government somehow never happened.

The ideal of consensus democracy finds its application mainly in culturally divided societies. It is based on proportional representation, a multi-party system, and a power-sharing executive. Switzerland has been that way since 1959.

In all that period of its history, Switzerland was changing from the first to the second model, mainly due to the evolution of people’s rights.

Before 1919, free competition between political parties to form a majority government never really worked. For 60 years the Free Democrats won every election to both chambers of parliament, sometimes thanks to a certain amount of gerrymandering. A real change in power relations only came in 1875 as a result of the nationwide referendum votes.

With the emergence of a consensus democracy, the number of popular referendums increased. This had a great deal to do with parliament’s increasing use of legislation to fill gaps in the state’s provision of social benefits and infrastructure.

At the same time the oppositional mood of the voters waned. Whereas at the outset most of the referendums were successful, today three-quarters of them go the way parliament and government have recommended. What has remained constant is the amount of people’s initiatives – but only about 15% of all initiatives are accepted by the voters.

Decline of working class

A big change since those days has been the decline of the Swiss industrial working class – it has only a marginal existence now. Foreigners with no political rights have replaced it to a great extent on the Swiss political map. What was left of the Swiss working class is today integrated into the service economy and has largely become depoliticised.

Symbolic of all this change is the House of the People in the old town of Olten. It has disappeared and been replaced by a rather anonymous-looking building. Its name? “Hotel Europa.”

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.