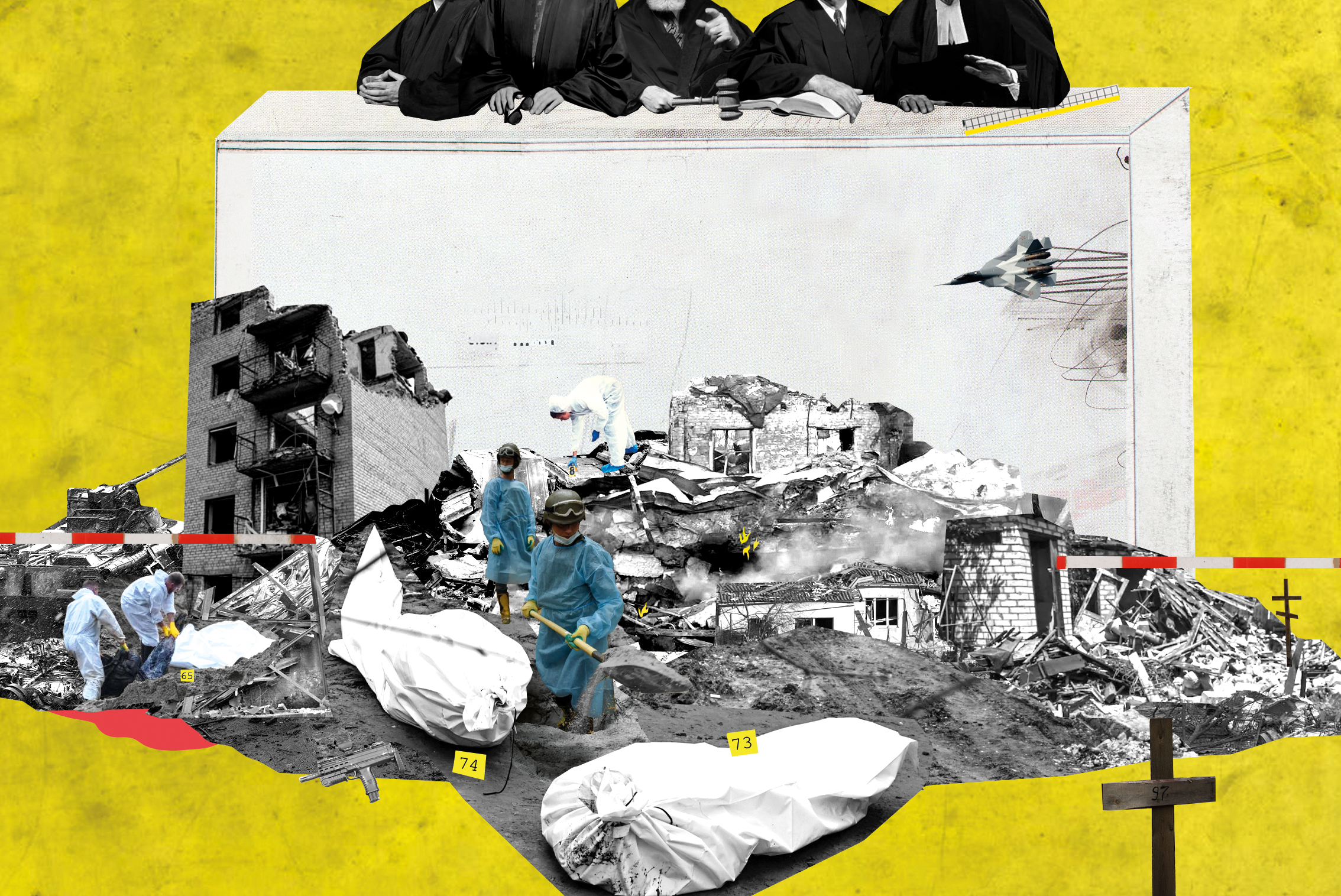

When is a ‘genocide’ really genocide?

Is genocide being committed in Gaza? While more and more experts in international law say it is, the issue continues to divide opinion, particularly among states. But who has the authority to decide on this issue? Using what criteria? And what are the consequences? Swissinfo asks two Geneva experts.

The United Nations has declared a famine in Gaza City, Israel has stepped up its military intervention on the ground, and only inadequate quantities of humanitarian aid is reaching the Palestinian enclave ravaged by two years of bombing. More and more specialists in international law are now talking in terms of genocide in Gaza.

This is also the case for a commission of inquiry mandated by the Human Rights Council, other independent UN experts, and international and Israeli NGOs. Nation states are still divided on the issue, with Western nations mostly shying away from use of the term genocide before a ruling by international judicial bodies. Israel denies any accusation of genocide.

What is genocide?

The term genocide was coined by a Polish jurist in 1944. The legal definition of the term is now enshrined in the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. This international treaty, adopted by the UN General Assembly, came about in the wake of the atrocities of the Second World War and the Nuremberg trials, where Nazi leaders responsible for the Holocaust were tried for crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes against peace (The crime of genocide did not yet exist in international law at the time of the trial).

This UN convention has two important features. The first identifies genocidal acts committed against a group (national, ethnic, racial or religious). There are five of these criminal acts specified:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

The other important feature is a genocidal intention. In other words, these acts – just one of which is enough to constitute genocide – must be accompanied by an intention to destroy the group, in whole or in part.

“The act is usually easy to prove, but the genocidal intent is not,” explains Paola Gaeta, professor of international law at the Geneva Graduate Institute.

Robert Kolb, professor of international law at the University of Geneva, points out that it must be proved that the accused not only wanted to kill members of the group but also that the killing involved an overall intention to eradicate the group in whole or in part.

“As distinct from war crimes and crimes against humanity, genocide has a very restrictive definition,” he says. “From a legal point of view, it’s not really worse than other crimes between nations. But public opinion sees these offences as a kind of hierarchy – and genocide as the crime that tops them all.”

>> >> Crimes against humanity, war crimes: to understand the difference between them and how they apply in the context of the war in Ukraine, read our article:

More

Explainer: International crimes and the Ukraine war

Who can commit genocide?

This question might seem trivial, but it is in fact essential. For example, can a state – as legally defined – commit genocide? “Strictly speaking, no,” says Kolb. “It’s not the state that commits genocide, but individuals. The state may be guilty of violating the convention against genocide.”

The convention requires the state to prevent the crime or punish it if it occurs. “One interpretation of the situation might be that the state is also required not to commit the crime itself. Still, we always speak just in terms of a violation of the convention.”

Who can label a case of genocide as “genocide”?

“That’s the wrong question,” Gaeta says. However, when it comes to Gaza, it’s the question everybody is asking. And when a journalist on French national television asked President Emmanuel Macron to take a position, he replied: “It’s not for a political leader to use that term – it’s for historians in due course.”

“Historians can certainly identify a case of genocide,” Gaeta says. “But politicians, NGOs, UN experts, lawyers and the courts can too – with different standards of proof, different timeframes, and sometimes different definitions.”

“The question of ‘who decides’ is not really the right one to ask, for the international community is by its nature anarchic,” she says. “There’s no centralised authority. From the point of view of international law, every state is free to come to its own conclusions. Countries don’t have to wait for a decision of the International Court of Justice to determine whether a case of genocide is going on.”

In the case of Rwanda, for example, many countries denounced the massacres there as genocide long before the international courts made their official determination. In recent years the US has condemned genocide in the Darfur region of Sudan and also in the province of Xinjiang in China, without international judicial bodies making a determination on them. Regarding Gaza, several countries such as Qatar, Brazil and Namibia have already pinpointed what they see as a case of genocide.

While the public tends to identify genocide with wholescale ethnic massacres, there is nothing in the convention’s definition of genocide to the effect that a people is actually eradicated; the intention to eradicate it is the key requirement.

So what role do international courts have?

International courts may also make a finding of genocide. Two courts have two different roles here.

- The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the highest court of the United Nations. It rules on disputes between states.

- The International Criminal Court (ICC) is the court recognised by 124 states to try individuals accused of the most serious crimes, including genocide.

- Also to be mentioned here are the special tribunals convened for certain situations, for example after mass killings in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

If one country thinks that another is in breach of the convention on genocide, it can bring an action before the International Court of Justice. South Africa and the Gambia did just this. South Africa accused Israel of genocide in Gaza and the Gambia charged Myanmar with genocide against the Rohingya minority. No judgement has yet been handed down.

The International Criminal Court, which hears cases against individuals and not states, can try people charged with this crime. It has, to date, never found anyone guilty of genocide. In late 2024 it issued an arrest warrant for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for crimes against humanity and war crimes. He denies the allegation. In 2023 it took the same action in the case of Russian president Vladimir Putin. He rejects the court’s jurisdiction altogether.

To date, only three cases of genocide have been determined by the international courts. The first was genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda. The perpetrators charged were found guilty by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. The genocide at Srebrenica in Bosnia was committed by Serbs who were found guilty by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Finally, the genocide against the Cham and Vietnamese minorities in Cambodia was the doing of the Khmer Rouge leadership. These officials were tried by the “Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia”, which was a combined effort of international courts and Cambodian jurists. The International Court of Justice also made a finding of genocide concerning the events at Srebrenica but did not convict Serbia itself on the charge.

History books tell of many more cases than this, such as the cases that eventually led up to the drafting of the convention. Perhaps the most notorious of these was the genocide of Armenians in the Turkish empire during the First World War. These cases are still outstanding political issues. The Armenian genocide, recognised by many states and some international institutions, is still denied by Turkey.

Can national courts try genocide?

Yes. Courts in a country affected may try people for this crime if the conditions for a trial are satisfied. So can third countries appealing to the principle of “universal jurisdiction”. This allows countries to try international crimes that occurred outside their national territory. In 2023 the Swiss courts convicted a former Liberian warlord for crimes against humanity.

What happens when a state or international tribunal determines a case of genocide?

Under the 1948 convention, states are obliged to prevent and punish the crime of genocide. “A state that finds genocide is going on has obligations to fulfil,” Kolb explains. “One obligation would be not to support or assist the crime; that is, it must not aid or abet the commission of genocide.”

The agreement explicitly forbids support of a genocidal intention. In the case of arms sales, for example, this would involve intending, knowing or having clear evidence that the arms supplied will be used to commit genocide, Kolb says. States may take counter-measures, that is, impose sanctions on a country they believe to be violating the convention.

What then would be the outcome if the ICJ determined that there is a case of genocide in Gaza? “Under international law, the basic legal consequences are all the same, whether a state is violating a trade agreement or the convention on genocide. It must desist from the illegal actions, not repeat them, and pay reparations,” Gaeta explains.

For the guilty party, genocide is a heavy burden to bear. For the victims, it’s a trauma on which the group builds its identity. “A narrative emerges that places states on the right or wrong side of history,” she concludes.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/livm. Adapted from French by Terence MacNamee/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.