2023 will continue to challenge Geneva’s international organisations

After two years marked by the Covid-19 pandemic, 2022 proved to be another tough year for Geneva’s international organisations. With no signs of peace between Russia and Ukraine, 2023 looks just as challenging.

“In 2023, we need peace, now more than ever,” read the annual New Year’s message of United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres. At an end-of-year press conference, Guterres confided that he was “not optimistic about the possibility of effective peace talks in the immediate future”. Though, he added, “I strongly hope that, in 2023, we’ll be able to reach peace in Ukraine”.

2022 saw a permanent member of the UN Security Council, Russia, invade another sovereign state, Ukraine. The world body responsible for global peace and security, in which Moscow has a veto right, could do nothing but watch. The attack soon triggered Europe’s largest refugee crisis since the Second World War. Together with the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change, the war aggravated a global food, energy and debt crisis that hit – and continues to hit – low-income countries the hardest.

In Geneva, UN aid agencies and other international NGOs struggled to respond to these massive challenges. Money was poured into Ukraine but started to dry up elsewhere. Human rights violations in certain parts of the world were successfully addressed, while others were swept under the rug. Old problems did not disappear, while new crises piled on. 2023 is set to be another difficult year for the multilateral system.

More

Inside Geneva: aid agencies reflect on 2022

War and food crisis

This year, the UN will continue to try to mitigate the impact of the war on the rest of the world. Slowing the spread of hunger will remain a top priority. With Russia the world’s largest producer of fertilisers and Ukraine a top exporter of grain, the war in Ukraine sent global food prices to record levels in March 2022. Many countries in Africa and the Middle East that rely heavily on imports could no longer afford basic commodities such as wheat.

More

How the war in Ukraine is fuelling the next global food crisis

Food prices have since fallen but remain too high, according to the UN. The drop is partly due to a deal, concluded in July 2022 under the auspices of the UN and Turkey, allowing Ukraine to export its grain through a safe corridor in the Black Sea. A side-deal to facilitate the export of Russian fertilisers was part of the package. But these remain largely unavailable and overpriced on global markets.

Making sure Russia and Ukraine agree to extend the Black Sea grain deal as its renewal date approaches in March 2023 will be a key objective for top UN officials. Ensuring Russian fertilisers are available at fair prices everywhere will be another.

More

Extended Ukrainian grain deal offers temporary relief to food crisis

Humanitarian needs and challenges

For Geneva’s aid agencies, 2022 was a year of unprecedented humanitarian needs, caused by crises of exceptional scale: wars, climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic. 2023 is now set to break that record. The UN estimates that it will need $51.5 billion (CHF47.4 billion) – $10.5 billion more than its 2022 budget at the same time last year – to assist some 230 million people across 69 countries.

Meanwhile, the funding gap – between needs and money raised – has never been wider. It is forcing aid agencies to make difficult decisions about whom to assist. The massive show of support from donors in the West for Ukraine has meant that other crises have remained largely underfunded. Shining the light on forgotten crises in places like Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan or the Horn of Africa will be a massive challenge for UN aid agencies in 2023.

More

How the war in Ukraine fuels underfunding for other crises

Located across the road from the UN in Geneva, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) also came under considerable pressure in 2022. Kyiv repeatedly criticised the organisation for not visiting Russian-held prisoners of war, despite having a mandate to do so under the Geneva Conventions. The ICRC has since been able to visit hundreds of detainees on both sides. It will hope to visit more in 2023 but will need Russian and Ukrainian officials to cooperate.

More

Families of Ukrainian war prisoners ask the Red Cross to do more

Now under the leadership of its first female president, Mirjana Spoljaric Egger, the ICRC will also strive to advocate for the respect of international humanitarian law, the rules of war, a task as difficult as ever.

Ideological battle over human rights

In 2023 the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), a set of 30 articles laying out the basic rights and freedoms of all individuals which the UN adopted in response to the horrors of the Second World War, will turn 75.

The document reflects “universal values that transcend cultures, nations and regions” and sets out the “inalienable rights to which all human beings” are entitled. But its legitimacy is today contested, chiefly by China, which argues that there are no such thing as universal values, and that the UN document is a Western concoction.

In Geneva, the new High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, will hope to re-establish the currently fading global consensus on human rights. China is pushing for a greater emphasis on collective rather than individual rights. But Türk argues both go hand in hand. Speaking to journalists in December 2022, he said that “written and adopted by representatives from all regions of the world, the UDHR makes it clear human rights are universal and indivisible; and human rights are the foundation for peace and development”.

More

UN rights chief in China: walking a tightrope between engagement and risk

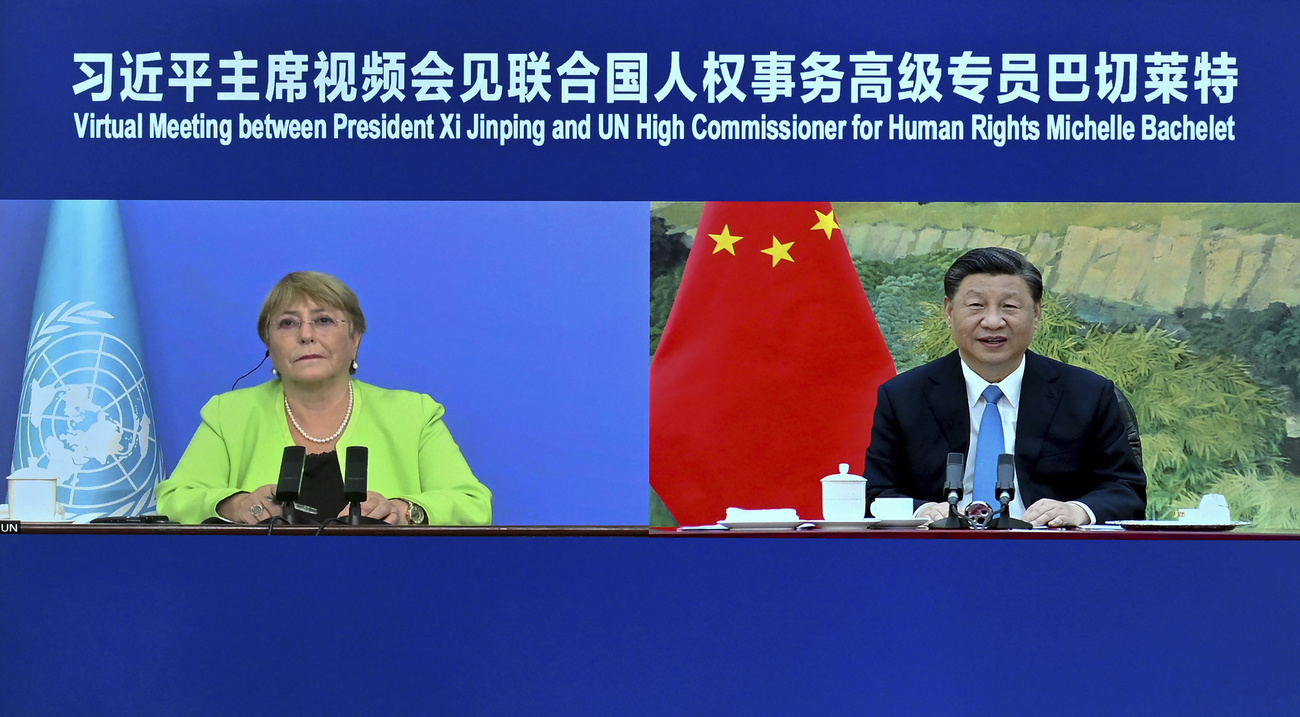

How the UN human rights chief follows up on a report his office produced on Beijing’s alleged abuses against the Uyghur Muslim minority in China’s Xinjiang region represents a major test for him. The report was published minutes before Türk’s predecessor, Michelle Bachelet, left office. It points to potential crimes against humanity committed by China, but Beijing has dismissed the report’s content as lies promoted by hostile Western forces.

At the Human Rights Council’s latest session in October, a proposal to hold a debate on the report was voted down, highlighting China’s growing influence on the 47 members of the Geneva-based UN body. Türk may choose to engage behind the scenes with the Chinese authorities on ways to implement the report’s recommendations. But he may also choose to address the report publicly, either at a future Council session or through issued statements.

More

Human Rights Council vote on China reflects shift in power

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.