The effects of 1.5°C global warming in Switzerland and beyond

The goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels will not be achieved. We outline the possible consequences of crossing this threshold for life on Earth and in Switzerland, a country already heavily affected by rising temperatures.

“We will not be able to contain global warming below 1.5°C in the next few years,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres said on October 22 at the World Meteorological Organisation’s congress.

In the series “10 Years of the Paris Agreement”, we highlight what has been done in terms of emissions, renewable energy, climate policies and climate research in Switzerland and around the world since 2015.

The comments by Guterres confirmed what much of the scientific community had already known – that the most ambitious goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement will not be reached.

Climate researchers in Switzerland predict that global temperatures will rise by 2.5°C by the end of the century:

More

Climate experts in Switzerland: 1.5°C target is out of reach

Why is the 1.5°C threshold considered to be critical, and what might be the impact of a greater increase in Earth’s temperature for ecosystems and human activities? Here are the answers to some of the fundamental questions on climate change.

Where does the 1.5°C limit come from?

In 2015, almost every country in the world including Switzerland signed the Paris Climate Agreement, the first universal and legally binding treaty to reduce emissions. States set a goal to limit average global warming “well below 2°C” compared to pre-industrial levels (which are based on the 1850-1900 average), aiming for a maximum increase of 1.5°C.

The two-degree bar stems from a series of scientific studiesExternal link, some dating back to the 1970s, which found that greater global warming would result in an unprecedented situation for human civilisation. The consequences would not only harm the Earth’s flora and fauna but would be catastrophic for humans. Countries officially adopted the two-degree limit at the Cancun Climate Change Conference in 2010, believing it to be ambitious but within reach.

But in the years that followed, countries most vulnerable to climate change, particularly small island states, called for a review of this target, arguing that unsustainable disruptions would be possible even before the two-degree threshold was reached. In 2015, based on the latest available scientific evidence, the safe limit was lowered to 1.5°C.

The agreement, adopted on December 12, 2015, at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris, is the first international and legally binding climate agreement. It commits all countries to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The goal of the agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, aiming for a maximum increase of 1.5°C. To achieve this, net-zero emissions (climate neutrality) must be reached by 2050.

The agreement was signed by 196 countries. Switzerland ratified it in 2017.

Why is 1.5°C considered a critical threshold?

A special reportExternal link by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published in 2018 stressed the importance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C to preserve the integrity of the climate system and reduce the risks associated with rising temperatures.

Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, has said that the 1.5°C target is not comparable to targets in other policy negotiations, on which compromises can be made. A rise of 1.5°C is not an arbitrary or political number but a planetary boundary, he told The GuardianExternal link newspaper.

This does not mean that exceeding the threshold by even a tenth of a degree will cause the end of the world. But limiting warming as much as possible can reduce the likelihood of irreversible changes to the climate and thus the planet.

A warming of 1.5°C is preferable to one of 1.6°C, and every tenth of a degree that is avoided reduces the risk of approaching a point of no return, such as the melting of West Antarctic ice, says Sonia Seneviratne, an expert on extreme climatic events who is a professor at the Swiss federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

What would be the consequences of a 1.5°C warming?

Extreme weather events such as heatwaves, droughts and heavy precipitation will become more frequent. For example, the frequency of extreme heat waves, i.e., those that occurred once every fifty years in the late 1800s, increases by nearly nine times under a 1.5°C scenario.

These exceptional events and natural disasters will cause an increasing number of casualties around the worldExternal link and result in a loss of biodiversity. They will also reduce crop yields and drive more people to migrate to more fertile lands sheltered from rising sea levels.

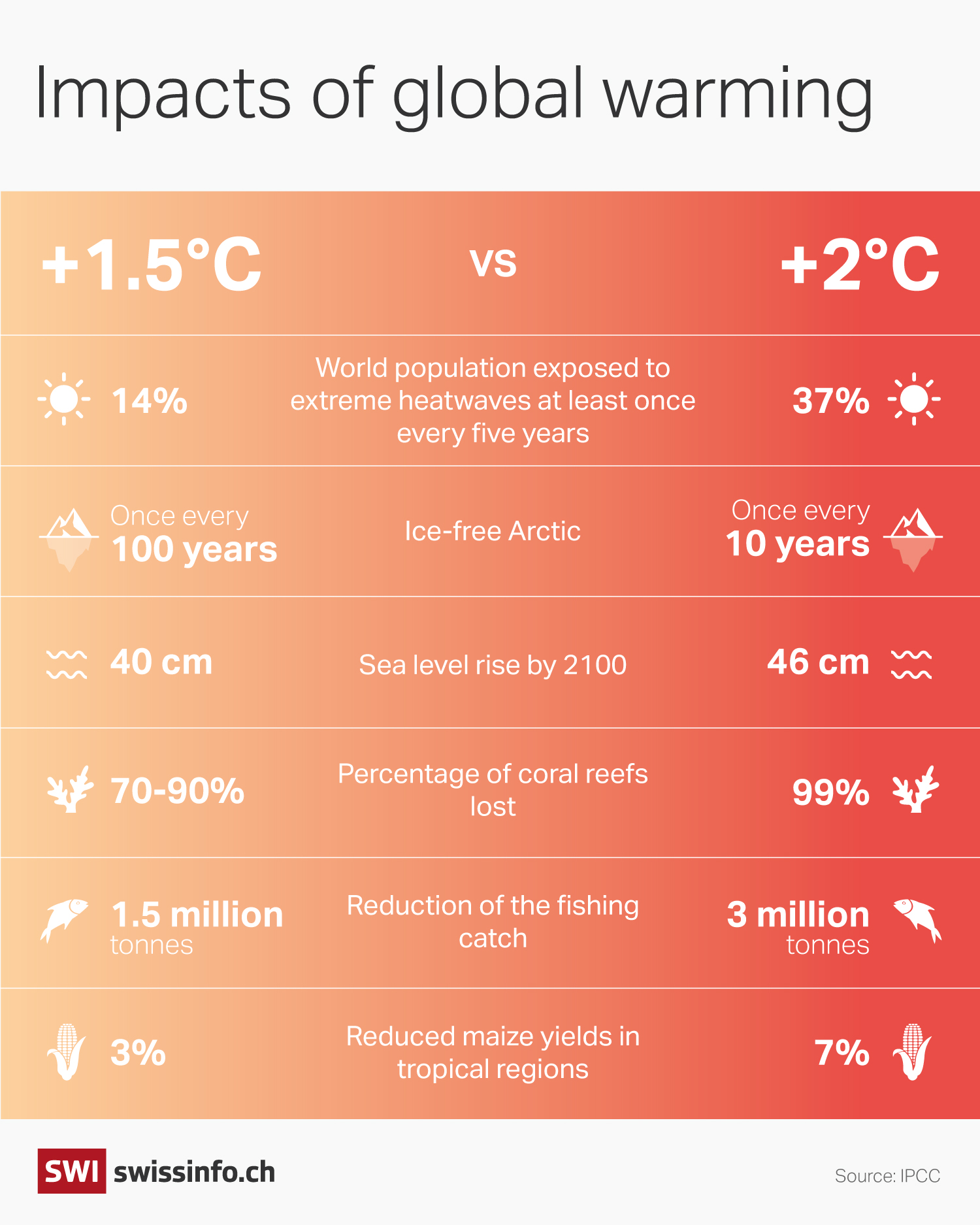

The graphic below illustrates the population and ecosystem impacts of global warming of 1.5°C and 2°C, respectively.

How would it impact Switzerland?

Switzerland is already heavily affected by climate change, with long hot and dry periods in summer, inexorably melting glaciers and snow-poor winters. In recent years, the country has “anticipated extreme phenomena that could worsen and become more widespread in the near future,” according to Erich Fischer, a researcher at the Institute of Atmospheric and Climate Sciences at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich and co-author of the IPCC reports.

Switzerland has a continental climate and cannot benefit from the cooling effect of the oceans. It is also located in mid-latitudes. In general, regions located toward the poles experience more warming effects than those at the equator. Snow and ice also play a role: when they melt, the exposed surface reflects less sunlight and absorbs more heat, contributing to rising temperatures.

Read more about how Switzerland is heating up particularly fast compared to other countries:

More

Why Switzerland is among the ten fastest-warming countries in the world

In Switzerland, the 1.5°C threshold was crossed at the turn of the new millennium, and average warming for the period 2015-2024 was 2.8°C, almost double the global average, according to the Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology.

A global warming of 1.5°C would roughly correspond to three degrees of warming in Switzerland. Under this scenario, the melting of Alpine glaciers will accelerate and there will be less snow at lower altitudes. In general, it will rain less in summer – when agriculture needs water most – and more in winter, Samuel Jaccard, a climatologist at the University of Lausanne explains.

Jaccard points out that we have all experienced extreme weather events, whether a heat wave or a devastating storm, such as the one that hit the Swiss city of La Chaux-de-Fonds in July 2023.

“With the multiplication of these extreme events, we’re starting to see measurable and tangible impacts that affect everyday life,” he says. Jaccard refers, for example, to the uptick in mortality during heatwaves or the increase in prices of some foods due to drought.

But it’s not too late to avoid the worst-case scenario. In its latest synthesis report, the IPCC points to multiple “feasible and effective” options to reduce emissions and ensure a liveable future on Earth.

The video below explains how climate change is altering the Swiss landscape, economy and its people:

Edited by Sabrina Weiss/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.