COP 15, a summit to halt the mass extinction of species

The biological diversity crisis affecting every corner of the globe can no longer be ignored. The United Nations Conference on Biodiversity (COP 15) opens this week in Montreal, Canada, and aims to reach a historic agreement to avert a mass extinction of fauna and flora.

“I live in Edinburgh but grew up in the countryside. During my childhood I enjoyed drawing an abundance of wild flowers. There were always wild meadows near our house, they don’t exist now.”

“I currently live near the beach in Lombok, Indonesia. I hardly come across any fish during my daily swims.”

“Fireflies: I used to see them in Lugano’s Mount Bre in the evening.”

As shown by the various contributions to our debate by SWI swissinfo.ch readers, biodiversity – that is, the variety and variability of plant and animal life on Earth – is in decline worldwide.

More

The above testimonies are mere drops in an ocean of evidence laid out in countless studies. WWF’s Living Planet Report 2022External link noted an average 69% decrease in monitored wildlife populations between 1970 and 2018.

Meanwhile, the latest reportExternal link by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), published in 2019, concluded that 25% of fauna and flora are threatened, suggesting that around 1 million specials already face extinction.

The situation is so dramatic that part of the scientific community is warning of the sixth mass extinction in the history of our planet.

The next major effort to halt this process will be undertaken at the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity. It is being held in the Canadian city of Montreal from December 7 to 19.

The hope is that, at the end of the summit, a historic agreement will be signed to stem biodiversity decline by 2030 and to restore it by 2050 (see box).

The Framework comprises 21 targets proposed for 2030, en route to “living in harmony with nature” by 2050. Key targets are to:

- Ensure that at least 30% globally of land and sea areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas.

- Prevent or reduce the rate of introduction and establishment of invasive alien species by 50%, and control or eradicate such species to eliminate or reduce their impacts.

- Reduce nutrients (fertilisers) lost to the environment by at least half, pesticides by at least two-thirds, and eliminate discharge of plastic waste.

- Use ecosystem-based approaches to contribute to mitigation of and adaptation to climate change, contributing at least 10 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) per year to mitigation; and ensure that all mitigation and adaptation efforts avoid negative impacts on biodiversity.

- Redirect, repurpose, reform or eliminate incentives harmful for biodiversity in a just and equitable way, reducing them by at least $500 billion per year (CHF500 billion).

- Increase financial resources from all sources to at least $200 billion per year, including new, additional and effective financial resources, increasing by at least $10 billion per year international financial flows to developing countries.

How COP 15 came about

The Convention on Biological Diversity was signed, together with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), at the UN Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1992. It has since been ratified by 197 States, including Switzerland.

The Conferences of the Parties arising from the UNFCCC spawned the 2015 Paris Agreement, a landmark treaty to substantially reduce greenhouse gases. Meanwhile, the Convention on Biological Diversity led to the Aichi targets – named after the part of Japan where the COP 10 on biodiversity was held in 2010.

So far, the results have been disappointing. Although there is greater public awareness of the importance of biodiversity and the percentage of protected areas has increased, none of the 20 targets set for 2020 have been fully achieved, laments Cornelia Krug, University of Zurich scientist and director of bioDiscoveryExternal link, who will be attending COP 15 as an observer.

More

The Swiss Alps are beautiful, but are they biodiverse?

Not just about climate change

When talking about the negative impact of human activity on nature, people think primarily of climate change and CO2 emissions. Global warming is, however, just one factor that is harming biodiversity and, although increasingly significant, it is not even the main one.

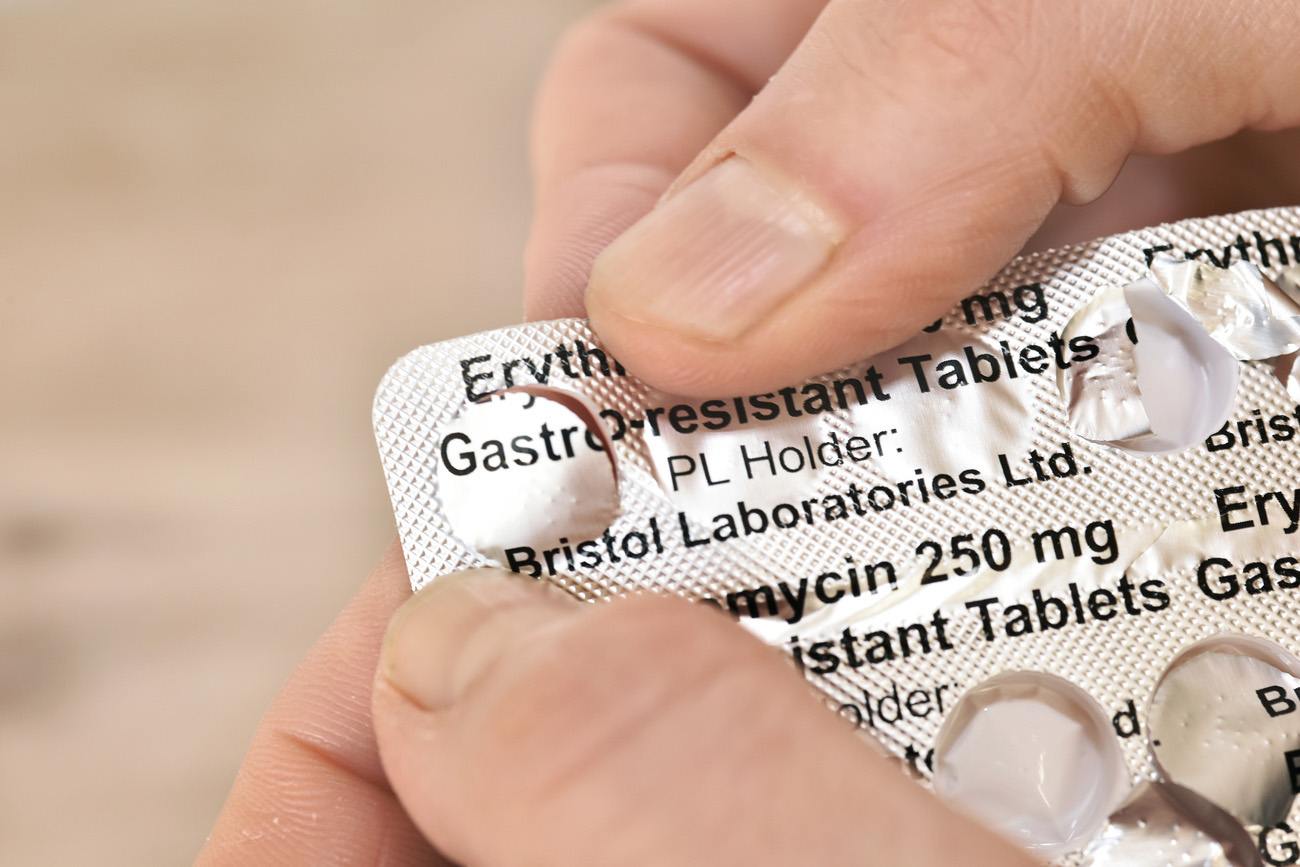

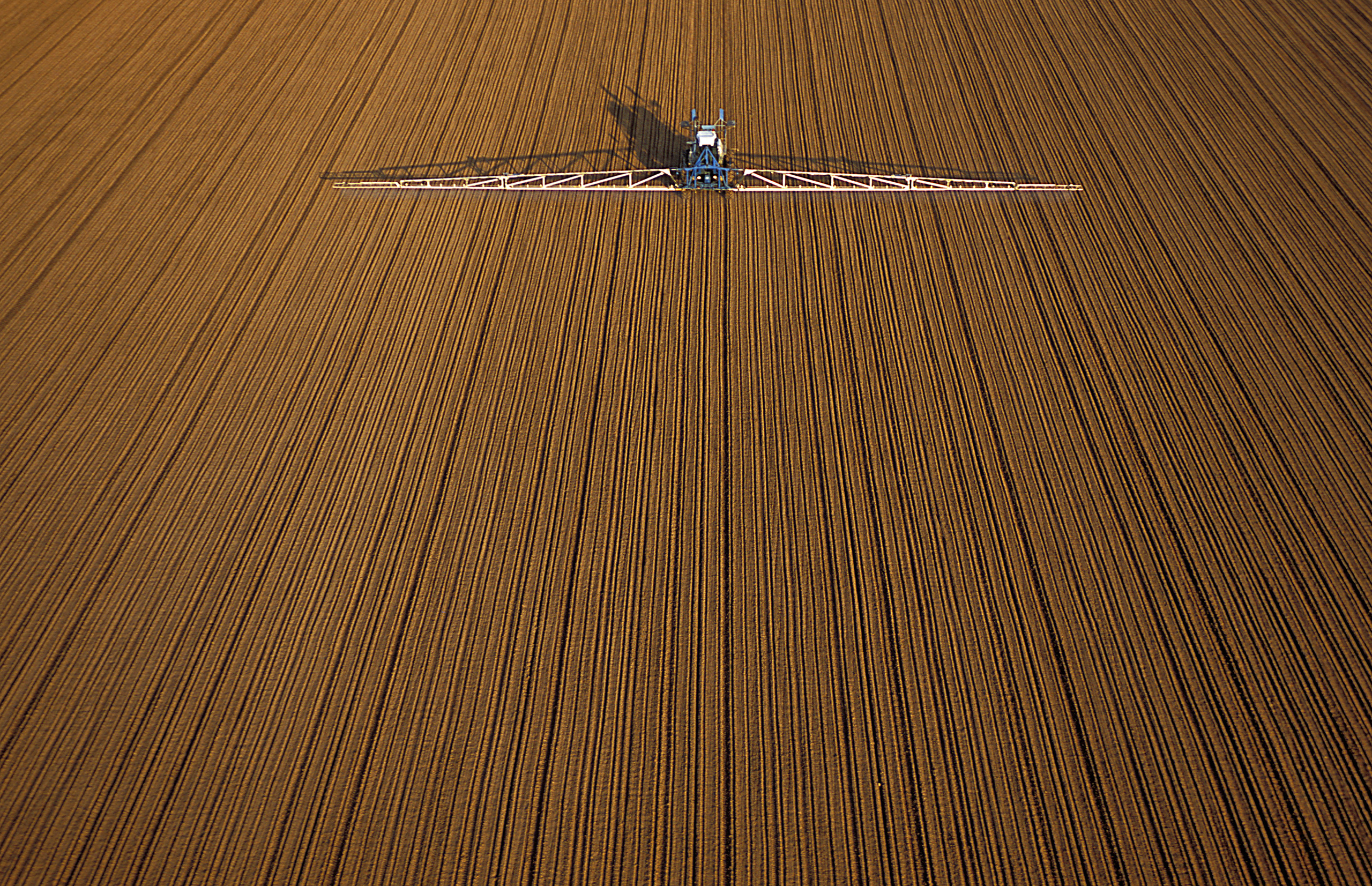

“Land-use change, for instance for agriculture, is one of the main drivers of extinction,” Krug explains. “Another is pollution. Not just plastic in the oceans, but also the overuse of pesticides and fertilisers.”

Krug and her colleagues are convinced that global warming and the loss of biodiversity are two issues that must be tackled in parallel and simultaneously. Otherwise, the world will face a situation where initiatives taken to limit greenhouse gas emissions come at the cost of wildlife diversity. Take large-scale reforestation for bionergy productionExternal link, for instance. A monoculture of poplars guarantees good CO2 absorption but is very poor in biodiversity. Moreover, as IPBES warns, if these crops replace land used for subsistence farming, the food security of local communities is also put at risk.

What are the hurdles to reaching an agreement?

The organisation of COP 15 has been fraught. Initially scheduled for October 2020 in Kunming, China, it was postponed several times before being moved to Canada.

China will still chair the summit, although it does not seem to give it much weight. Indeed, Beijing has not invited any heads of state (only ministers and NGOs). The Chinese leader Xi Jinping himself will not attend, just as he did not take part in the COP 27 climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh.

Compounding Chinese passivity are the problems of energy and food shortages stemming from the war in Ukraine, which increasingly top the list of priorities for many countries.

All this is even before dealing with the substance of the matter, namely the different points in the draft agreement that are most likely to spark opposition by countries.

Krug highlights three main possible stumbling blocks, all related to funding. The first is where to find the financial resources to implement any agreement. Already at COP 27, the economically developed countries were clearly reluctant to put their hands in their pockets.

The second potential hurdle concerns the equitable sharing of benefits – in other words, ensuring that a fair portion of the profits derived from the use of a country’s biological resources are returned to the country itself and do not go, for example, only to the multinational company exploiting the resources.

Last but not least, there is the burning issue of public subsidies. Many of these, even in Switzerland, support agricultural (and other) activities that harm biodiversity. The reduction in such subsidies envisaged in the draft agreement is likely to trigger considerable political resistance.

Despite all these difficulties, however, there is a glimmer of hope, according to the scientist Krug. One clear message coming out of COP 27 is that protecting and restoring nature are crucial to achieving climate goals. Moreover, the decision taken in Sharm el-Sheikh to set up a fund to pay developing countries for loss and damage caused by climate change is also an important step for the protection of biodiversity, which is generally greater in developing countries.

What are Switzerland’s priorities for COP 15?

Switzerland is setting its sights high. It is a member of the High Ambition CoalitionExternal link, which supports the goal of protecting at least 30% of the planet’s land and ocean area by 2030.

In Montreal, Switzerland will fight for an agreement containing high targets with time limits and the introduction of indicators for measuring progress, explains Eva Spehn, science officer at the Swiss Academy of Sciences (SCNAT)External link and a member of the Swiss delegation. “More and better financial means must be provided by countries that are able to do so, and private funding sources should in turn be aligned with the targets,” she says.

How well does Switzerland protect its biodiversity?

Despite its ambitions, Switzerland’s own performance in protecting biodiversity is far from impressive.

The Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention), meeting in Strasbourg, took Switzerland to task recently for its inaction with regard to protected areas. The country was found to rank bottom of the class in Europe for action in this field.

Switzerland has some 56,000 recorded plant, animal and fungal species, according to a summary of the monitoring of the red listsExternal link of endangered species to be published in 2023 by the Federal Office for the Environment and by InfospeciesExternal link. Experts estimate anoter 29,000 species live in the country. The 2022 edition of the journal HotspotExternal link, published by SCNAT, gives a preview of the findings. Around 35% of the 10,844 observed species are endangered in Switzerland, Spehn noted.

In a written response to SWI swissinfo.ch, the scientist explains that measures have already been taken to prevent biodiversity loss, but more action is needed to reverse the trend. For this, the pressure brought to bear by the factors causing it must be reduced. These include agriculture, building, infrastructure development and habitat fragmentation. From 1985 to 2009, some 15% of Swiss territory was transformed.

Then there is the thorny issue of subsidies. In 2020, SCNAT and the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research identified 162 subsidies that are harmful to biodiversityExternal link, in areas spanning agriculture, energy, transport and tourism. The subsidies are worth CHF40 billion ($43 billion), that is 30 to 40 times the amount available for measures to promote biodiversity.

Translated from Italian by Julia Bassam/ds; edited by Veronica DeVore

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.