Swiss efforts in Cyprus thwarted by reality

Sixty years ago, Cyprus gained independence from Britain. The Swiss played a significant role in the process and continued to be an example for the small island state during the following decades. However, the results remain mixed.

On August 16, 1960 Cyprus became an independent state. This followed over five years of an armed campaign by EOKA, the guerrilla National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters, against the British colonial forces.

Switzerland was one of the first countries to recognise the Republic of Cyprus. The Swiss authorities, together with the British, Greek and Turkish governments, had accompanied the British crown colony on its way to independence. The small Alpine nation, as the only neutral party in the complex conflict, had offered its good offices in a credible manner.

From February 6-11, 1959 the prime ministers of Greece and Turkey met at the Grand Hotel Dolder in Zurich and reached an agreement to end the civil war in Cyprus. This paved the way towards the island becoming an independent state. On February 19, following a conference in London, an agreement was signed to finalise the settlement of the Cyprus dispute, known as the Zurich and London Agreements.

Swiss professor

However, this was not the end of Switzerland’s efforts to support Cyprus. The biggest test was still to come. Since the end of the 19th century, the Greek Cypriots had supported the idea of “Enosis” – union with Greece – while Turkish Cypriots wanted “Taksim”, the partition of the island between Greece and Turkey. The hope was that the two opposing groups would be satisfied by a balanced constitution. One month after the Zurich meeting, a commission started to draft a constitution text under the leadership of a Swiss professor.

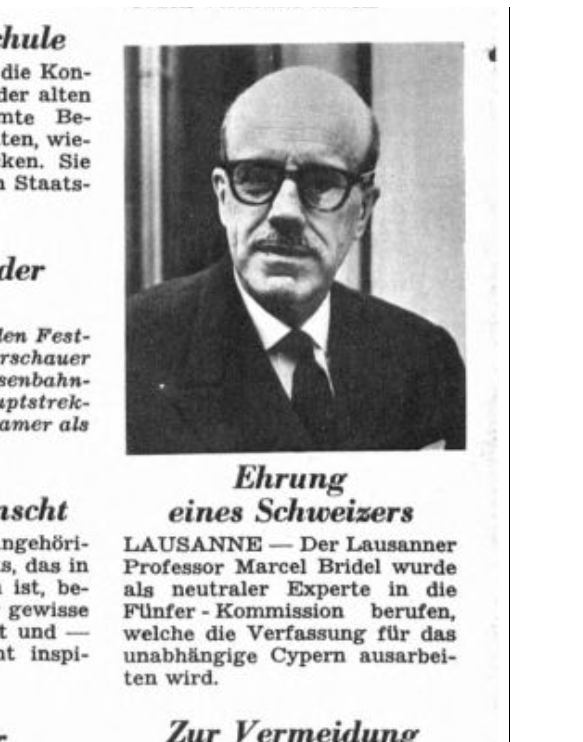

Marcel Bridel, who held a chair in constitutional law and comparative institutional theory at the University of Lausanne, was brought in to add some Swissness to the process. Cyprus’ future political system was to have a federal structure, just like that in Switzerland. As a neutral legal advisor, the professor from the French-speaking part of the country played an active role in the complex negotiations. The aim was to establish a generally acceptable set of rules for the political compromise between the colonial power of Great Britain, Greece, Turkey and the Cypriots.

The founding treaty included a progressive constitution based on the European Convention on Human Rights, which was adopted a decade earlier. Considering that the two ethnic groups had fought a bloody civil war, a comprehensive Charter of Fundamental Rights was drafted. Bridel pushed for it to cover not only political and civil rights but also social rights. This made Cyprus‘ future constitution even more progressive than those of most European countries. It also gave Turkish Cypriots, who were in the minority, extensive rights of co-determination. This move held considerable potential for conflict, which only became apparent later.

The Swiss were satisfied with their role as a mediator. On April 23, 1959, the German-language newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung wrote: “By choosing a Swiss lawyer, the governments in Athens and Ankara have shown their respect for our institutions and their belief that the future Cypriot state can learn from them.”

Switzerland was well known for its influence in the region. For example, in 1926 a civil code identical to Switzerland’s entered into force in Turkey. The Turkish Cypriot leader Fazıl Küçük, who was at the Zurich negotiations, had also studied medicine in Lausanne and knew the country well.

Not a good sound

On paper, the compromise between the two ethnic groups looked promising, but realistically it had little chance of survival. The rift between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots was too deep and the constant pressure from abroad led to complicated political entanglements. The first president of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios, repeatedly stressed that the constitution had been forced upon the Cypriots.

In 1961, a diplomatic dispatch revealed that some people inside the Swiss foreign ministry were unhappy with the constitutional draft. “Even though it is true that Professor Bridel is an excellent expert in constitutional law, there are currently so many hurdles, national resentments and dashed hopes associated with the implementation of the constitution of Cyprus that it may take another generation to do justice to Bridel’s work,” it stated. For the islanders, “Zurich” “doesn’t have a good ring to it right now”.

The 1960 constitution proved unworkable and was only in force for three years. When the Greek Cypriots called for a constitutional reform in 1963, all the bottled-up tensions between the two sides exploded and led to another civil war. Formally, the constitution drafted under Bridel’s leadership has never been amended. However, in practice it was changed so that it only applies to the Greek Cypriots. And since the Turkish invasion in 1974, both communities have remained physically separated.

Failed attempts

Switzerland was to serve as a role model for Cyprus years later, just before it joined the European Union. A plan proposed by the former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan foresaw a confederation consisting of two largely independent states, just like the Swiss cantons. Once again, Switzerland participated in drafting the plan and hosted the negotiations at the luxury Bürgenstock resort near Lucerne. In 2004, the so-called Annan Plan was put to the people in a referendum, and even though it was supported by 65% of Turkish Cypriots, 76% of Greek Cypriots rejected the plan.

Switzerland offered its good offices diplomatic services again in 2017 when a new attempt was made to reunite the island. The two parties met at Mont-Pèlerin, Geneva and Crans-Montana, but once again the negotiations were unsuccessful.

After sixty years of independence, the Republic of Cyprus is still not at rest. It is not Professor Bridel’s fault that the process got off on the wrong foot. The conflict was too complex, too many parties with different opinions were involved, and in the end, Bridel’s role was too low key. The plans to export the Swiss magic formula to the Mediterranean were eventually drowned in the stormy reality of the divided island.

On August 14 Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis met with his Turkish counterpart Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu in Bern to discuss bilateral relations including the issue of Cyprus.

During the meeting Switzerland reiterated its offer to provide its good offices to help find a solution to the Cyprus issue, which it had previously presented in 2019.

“It is in Switzerland’s interest to continue on the path of open and constructive dialogue with Turkey,” said Cassis.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!