What future for Francoprovençal?

Although Swiss multilingualism is protected by law, native speakers of a patois spoken in pockets of western Switzerland are dying out. Sociolinguist Jonathan Kasstan looks at efforts to keep Francoprovençal alive by passing it onto adult learners.

Those following President Hollande’s final months in the Élysée will perhaps have noticed his office turning their attention to the promises made in the very early days of his campaign.

Among those made that have long been relegated to the bottom of the list is the ratification of the Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (or simply ‘the Charter’), first signed in 1999, and since left in a policy limbo. The Charter, which first appeared in 1992 under a Council of Europe initiative, deals with provisions to protect and promote the use of regional or minority languages.

However, some 16 years on, the Charter remains unratified by the Élysée, given that ratification would almost certainly require amending France’s Constitution, where Article 2 states “la langue de la République est le français”.

In spite of a recent resurgent interest in ratification, following various inquiries into the feasibility of constitutional amendment (see most recently Le Monde from August 9), no real progress has been made, nor will it in the eyes of some, as nearly two centuries of nation-state policy geared towards monolingualism has left the majority of France’s regional languages in a state of terminal declineExternal link.

Constitutional safeguard

Conversely, just over the border, in Switzerland, multilingualism is safeguarded by Article 116 of the Constitution, where federal law has long protected “la diversité des langues et des cultures dans un seul état” (diversity of languages and cultures in the state).

However, as Irish language revitalisers will know all too well, state support alone does not make for healthy speaker numbers, and regional languages that are, in theory, supported under Swiss law, are nevertheless also in decline. This is largely due to the perception that there is no real socio-economic incentive on the part of the speakers to transmit these languages down the generations in a more globalized world, where socio-economic mobility is linked directly with a handful of dominant prestige languages (predominantly English).

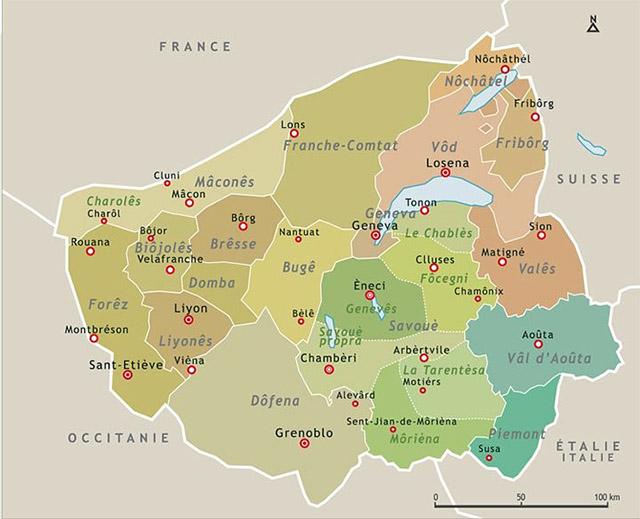

Among the most severely endangered languages found on both sides of the Franco-Swiss border is Francoprovençal: a much understudied Romance language spoken by less than 1% of the total regional population. While Francoprovençal was once a prestigious literary language, commonly heard in major conurbations such as Lyon and Geneva, today, the language is largely relegated to isolated rural pockets, where it is spoken only by the elderly.

These speakers, who refer to the language as ‘patois’ rather than ‘Francoprovençal’, are a source of real cultural treasure. As inter-generational mother-tongue transmission now only takes place in the most isolated of these rural pockets (e.g. last bastions such as Évolène in the Canton of Valais), the current generation of native speakers will be the last to command Francoprovençal as a native language. This, however, does not have to be an inevitable fate.

While clearly in a state of obsolescence, organisations orientated towards revitalisation and transmission continue to undertake important work on the ground.

The Fondation Bretz-Heritier, for example, publishes a regular journal on the language, and generously supports grass-roots initiatives that raise public awareness on the importance of linguistic and cultural diversity.

There remains, however, significant hurdles to progress. For instance, how might younger generations be encouraged to take up Francoprovençal as a second language, like English or German? How can efforts to transmit the language be streamlined, rather than relying on disparate and unintelligible orthographies? How can language movements with very different goals be encouraged to work together? The answers to questions such as these would encourage great strides in the revitalisation process. More recent efforts have now begun to tackle these larger questions.

Wider literacy

Second-language learner revitalisation movements are now springing up in the region, with ambitious goals orientated towards wider literacy and transmission rates throughout the regions where Francoprovençal is found in all its guises. These larger pan-regional efforts have long since been lacking in the conventional approaches to revitalisation of Francoprovençal.

Second-language learners such as those referred to here are characterised by linguists as ‘new speakers’: acquiring Francoprovençal in an educational context only, they are heavily motivated adult learners, who feel a deep sense of cultural attachment to the language, despite the fact that they were never raised speaking it. As a result, they tend to be very different in social and economic terms to the traditional native speakers referred to above, and there is evidence to suggest that these differences can sometimes foster sentiments of social and linguistic incompatibility (for example, see my blogExternal link).

It is noteworthy that Francoprovençal is not the first severely endangered language context to suffer this native speaker / new speaker dichotomy. In recent years, there has been an eruption in the number of endangered language studies documenting emerging new speakers.

Celtic

Breton, for example, is a Celtic language spoken in Brittany (north-western France). While studies have long shown a steady decline in native speakers, new speakers have been emerging since the 1970s in the context of bilingual and immersion Diwan schools. While early commentators on this phenomenon were quick to marginalise these speakers as ‘unauthentic’, these views have since changed. Michael Hornsby (Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań) for example has argued that new speakers of Breton might now be best placed to ‘keep the language alive until such a time that conditions will change so that it is spoken more widely than it is now’External link.

Although Francoprovençal new speaker movements are still embryonic by comparison with the Breton context, they have made significant headway in driving revitalisation at a larger pan-regional level.

The ‘Arpitan’ movement, for example, promotes a cross-Francoprovençal orthography that is designed to represent the largest possible number of disparate dialects (over 400 of them exist according to some estimations). This important device for driving revitalisation through pedagogical materials and other print media is, however, shunned by the wider native speaking community, whose interests tend only to be orientated towards the local level. This is a tremendous shame. As Nancy Dorian once argued in the context of East Sutherland Gaelic – now moribund: perhaps it would be better if these puristic attitudes towards language were better spent being channelled ‘into forms which are useful rather than harmful’External link, before it is too late. Unfortunately, it is now likely too late for East Sutherland Gaelic, but it need not be for Francoprovençal.

To return to the question posed above: what future for Francoprovençal? Any future is surely preferable to no future at all.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of swissinfo.ch

swissinfo.ch publishes op-ed articles by contributors writing on a wide range of topics – Swiss issues or those that impact Switzerland. The selection of articles presents a diversity of opinions designed to enrich the debate on the issues discussed.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.