Curious about drones? Here are the basics

It seems like drones are everywhere these days – in the news, in stores, and in the air above us. From technology and uses to risks and regulations, here’s a crash course (no pun intended) on this rapidly advancing technology.

Switzerland is at the forefront of drone innovation. Over the last five years, it has given rise to a “Drone Valley” of some 80 start-ups in the sector, many of which have spun off from leading research groups at the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology in Zurich and Lausanne. The country has also integrated aspects of drone use and safety into its aviation and data privacy laws.

“Switzerland plays a leading role in drone technology today,” said Swiss Transport Minister Doris Leuthard at the World Economic Forum Drone Innovator’s NetworkExternal link, held on June 26 in Zurich.

More

Why the Swiss are drone pioneers

“Innovative companies and universities driving the success, along with pragmatic government regulation that takes the needs of research and development into account: This unique mix has created an environment that is equally attractive for start-ups, companies and research.”

But as a relatively new technology, the increasing presence of drones in Swiss research, media and airspace is raising more and more questions about their potential applications, and potential risks.

Questions like…

What is a drone, exactly?

The first thing to know about drones is that the word ‘drone’ is not very precise, since it can describe a range of aerial, terrestrial, and even aquaticExternal link robots. But it’s most commonly used to refer to what are more accurately called unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs. When UAVs are talked about together with corresponding elements of ground control, they may be called unmanned aircraft systems (UAS).

What sets drones apart from other small aircraft like remote-controlled airplanes is that their technology incorporates elements of autonomy, or the ability to carry out certain functions like navigation, obstacle avoidance, and stabilisation without direct human input.

What’s the difference between the drones I see in my neighbourhood and those I see on the news?

The development and use of UAVs has military roots, dating back to the First World WarExternal link. The United States’ more recent use of military drones like the Predator and ReaperExternal link to gather intelligence and carry out missile strikes as part of the War on Terror mean that for some, drones are synonymous with warfare. But today the civilian drone market is booming, with more and more devices being developed for applications in sports, art, research, commerce, and humanitarian aid.

According to Faine Greenwood, a UAV researcher with the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative’s Signal Program, it’s important to make the distinction between today’s civilian drones and their military predecessors.

“People often imagine a direct evolutionary line between the Predator UAV and consumer drones, and that’s not true. There was a common origin of military tech, but it was a long time ago, and a lot of the consumer drones you see today are basically flying cell phones,” She told swissinfo.ch at a recent expert’s meeting on humanitarian drones hosted by swissnex Boston.

How do drones work?

Today, an internet search for consumer drones turns up an array of devices with different shapes, sizes, specifications and price tags – from ‘micro’ drones for the backyard costing under CHF100, to professional and high-end models that go for tens, or even hundreds, of thousands.

Despite the diversity of models available, most consumer drones have some key elements in common:

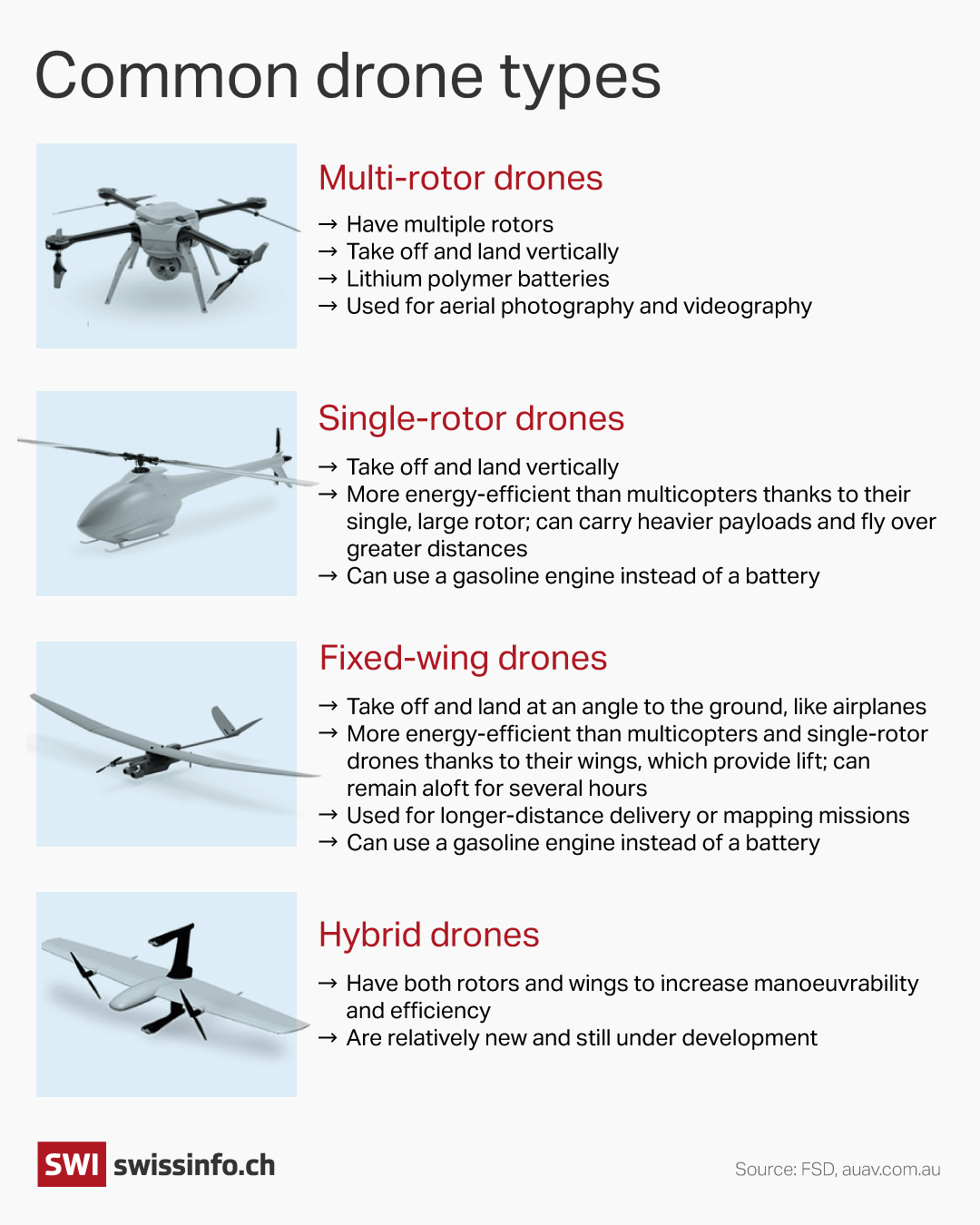

- Power: Most multi-rotor drones (see graphic) are powered by rechargeable lithium polymer (LiPo) batteries. Hovering using multiple rotors can be very energy-intensive, and with current technology, LiPo batteries can keep one of these drones aloft for a maximum of about 25 minutes. The aerodynamics of fixed-wing and single-rotor drones make them more energy-efficient than multi-rotors, and they can also run on engines powered by more energy-dense gasoline, making them a better option for longer-distance flights.

- Navigation: Many consumer drones come with a remote radio controller and are designed to be used with a smartphone and mobile app, to provide a first-person-view (FPV) display of the drone’s journey. Some even integrate virtual reality (VR) headsets to allow users to see the drone’s-eye-view. On-board sensors allow the drone to keep track of and maintain its position and speed, and many devices also have GPS to track their location. An average consumer drone must stay within a range of about 3.5-5 kilometres (2-3 miles) of the remote controller. However, that’s still far enough to exceed a user’s visual line of sight (VLOS), which some regulations require be maintained.

- Payload: This refers to a drone’s cargo, whether it’s a camera or a parcel. The weight and nature of the payload a drone can carry depends on the type of drone, the distance to be travelled, and climate and weather conditions. Drones are especially useful for delivering small, light, but crucial or time-sensitive payloads such as medical supplies to remote or inaccessible areas in so-called “last-mile” missions.

+ Read more about drone delivery in Switzerland

+ Read more about drones in humanitarian situations

- Autonomy: One of the most controversial aspects of drone technology is the potential for autonomy. Full autonomy in drones can generally be defined as an ability to navigate, execute tasks, and make decisions without any human input. Currently, most consumer drones integrate some elements of autonomous operation, but still require human control at various stages. Autonomous functions may include following a pre-programmed flight path, avoiding mid-air obstacles, homing in and orbiting an object specified on a map, self-stabilising, and returning to a set ‘home base’ location. Fully autonomous drones and their potential are the subject of much research and development in Switzerland: Davide Scaramuzza’s groupExternal link at the University of Zurich, for example, is developing autonomous aerial robots that do not require GPS or a remote controller, and navigate using a system of cameras and sensors to create maps of their location and trajectory.

Where can I fly a drone in Switzerland?

Civilian drone use has exploded in the past decade, and technological development is also accelerating. It’s hard for regulatory authorities to keep up, and those laws and guidelines that have been established vary from country to countryExternal link.

Regulatory concerns about drones tend to fall under two main headings: safety and privacy. Flying drones beyond a user’s VLOS and coordinating drone air traffic with that of full-sized aircraft is one major safety challenge. Another is the risk of damage to people or property, and of potentially dangerous drone payloads. As for privacy, the fact that most drones are equipped with cameras raises questions about what images and other data can be gathered, used and/or published without violating the privacy of others.

The Swiss Federal Office of Civil AviationExternal link has produced a decision-making guideExternal link with links to relevant permitsExternal link for those interested in flying drones in Switzerland, as well as a list of frequently asked questionsExternal link and answers.

The Office stipulates that special permissionExternal link is required for those wishing to fly drones…

- Weighing more than 30 kilograms (66 pounds)

- Closer than 5 kilometres to airfields and heliports

- More than 150 metres above the ground in control zonesExternal link

- Close to where emergency services are working

- Over, or less than 100 metres from, groups of people [more than 24 persons]

- Without direct eye contact with the drone

The Office also publishes the following interactive Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS) map of areas in Switzerland where air space is controlled or restricted for drones:

As for data privacy, Switzerland’s Federal Data Protection and Information Commissioner statesExternal link (in French, Italian and German) that videos taken by private consumer drones fall under the regulatory category of video surveillance. A private person recording a drone video that includes “identifiable persons” must respect the Federal Act on Data ProtectionExternal link, and specifically have a “justification” for processing the video data in the form of consent from the subject, or an “overriding private, public, or legal interest”.

Meanwhile, humans aren’t the only ones affected by drones. On July 4, the Swiss Environment Ministry, Federal Office of Aviation, and several environmental organisations published a brochureExternal link (in German and French) with recommendations for flying drones without harming or disrupting wildlife and wildlife habitat in Switzerland. Drones, the brochure states, may be perceived by birds and other wildlife as a threat that can “increase stress and provoke a flight or defence response”, and even impact their survival or reproductive success.

On June 26, the World Economic Forum held the inaugural forum for its new Drone Innovators NetworkExternal link at the Swiss Federal Technology Institute ETHZ. The network was inspired by the need for international airspace regulations to be adapted and harmonised to accommodate the potential of drone use in many areas, from cargo delivery to conservation, as well as minimise risk.

A highlight of the event was the first nationwide demonstration of an Unmanned Traffic Management System. The system is the first in Europe to allow users to track all registered drones in flight at any one time. According to a WEF press releaseExternal link, the system, which can also alert users when their drone is about to enter a no-fly zone, “is the equivalent of putting digital “stop signs” in the sky” and “lowers the barrier to entry for new pilots and improves overall safety”.

The demonstration was conducted by the Swiss Federal office of Civil Aviation, in cooperation with drone manufacturers Matternet, Parrot, and senseFly as well as air-navigation service providers AirMap and Skyguide.

Aerial Futures: the Drone FrontierExternal link is an ongoing event series created and curated by swissnex Boston, aimed at exploring the changes to policy and society that accompany the growing adoption and implementation of professional drone technology. swissinfo.ch publishes stories on the events and topics corresponding to the Aerial Futures series, in collaboration with swissnex Boston. You can follow the series on social media using the #DroneFrontier External linkhashtag.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.