Chinese philosophy expert in Switzerland despairs over plagiarism case

Swiss professor Iso Kern devoted much of his career to studying Chinese philosophy. Then his favourite student did something unexpected: he published Kern's work as a pirated copy.

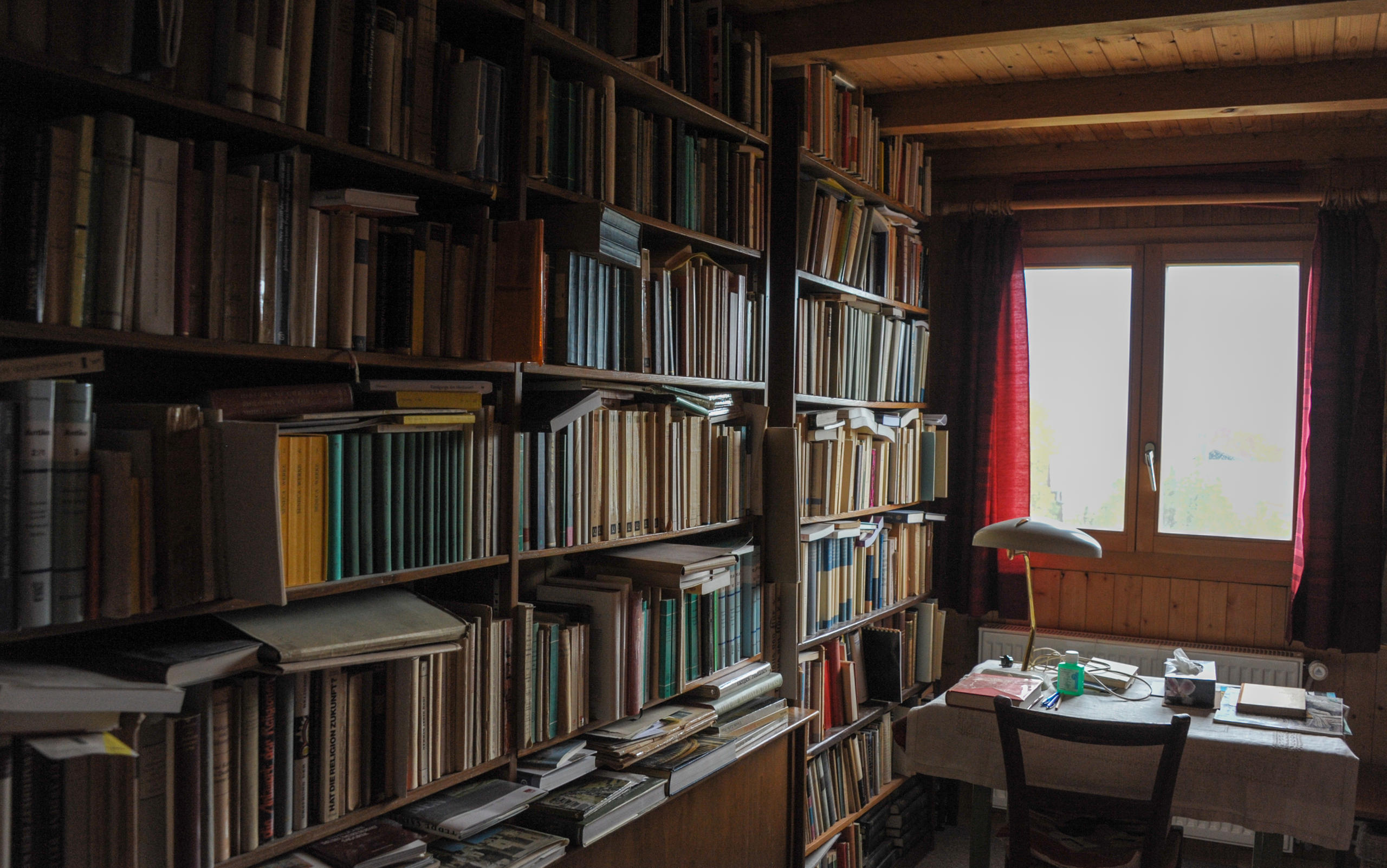

Far away from the noise of the city lies a small converted farmhouse, filled to the rafters with books. Iso Kern lives here, in the village of Krattigen on Lake Thun in the Bernese Oberland. Aged 85, he still writes for six to seven hours a day.

An old radio, a fixed-line telephone and his email address are his links to the outside world. In this wooden house, said his wife, Kern has completely immersed himself in the world of philosophy.

He has called this place home since he retired 20 years ago. He thought it would be peaceful and quiet. But something happened that turned his life upside down.

Kern is known in China as Geng Ning. He is a luminary of philosophy there, having spent decades studying the Chinese philosopher Wang Yangming. In doing so, he built a bridge between eastern and western philosophy. This bridge is his life’s work – large, robust, and radiant.

In July 2022, a camera team from Hong Kong came to Krattigen. They were filming a documentary series called The Hanologist. Kern plays the main role in this film.

“It was only then that the people of Krattigen found out that such a renowned professor lived in their village,” said Liu Yi, the director and producer of the film.

Liu’s intention is to tell Kern’s full life story. She and her team also travelled to the University of Leuven in Belgium. Kern worked there as a young philosopher.

Exercise in humility

This story revolves around one of Kern’s papers of that era. It is a story of humility and diligence; of friendship, betrayal and a rift so painfully wide that no bridge can overcome it.

At the centre of the story is the three-volume German edition of the so-called Husserl Collection. Edmund Husserl was a German philosopher. Born in 1859, he is considered the founder of phenomenology. Loosely speaking, Husserl saw philosophy as the primary discipline from which everything else springs. In all science, according to Husserl, a given phenomenon should be the starting point for all knowledge.

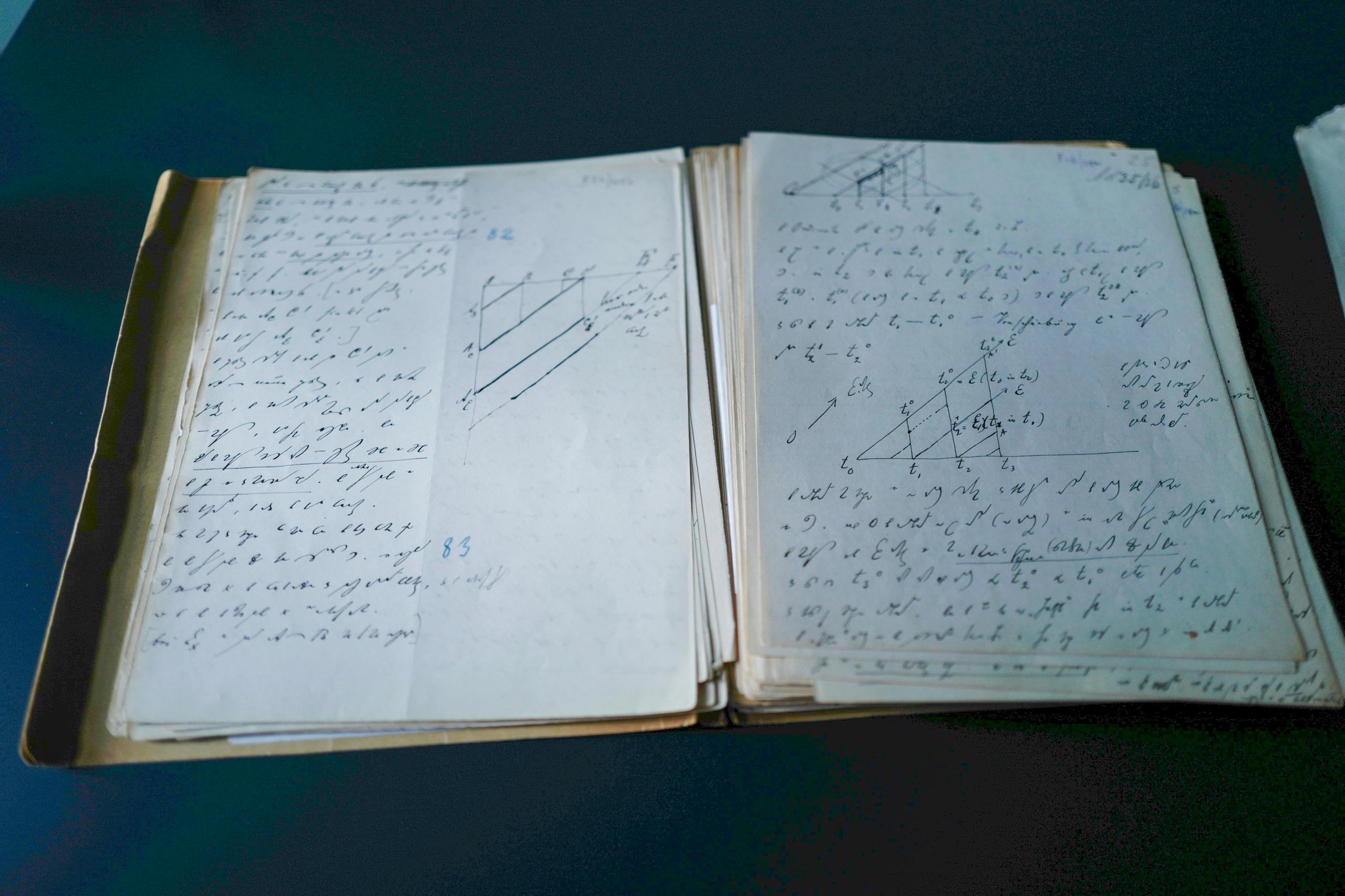

This is not easy fare. For Kern, it was an enormous body of work. As a young man, he researched and published the shorthand notes Husserl had left – 40,000 pages, gathered under the title Zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität (On the Phenomenology of Intersubjectivity).

It was an exercise in humility. “Husserl’s philosophy is very difficult to understand,” said Kern. “It took me two years.” But first he had to find and compile Husserl’s texts, then translate the spidery shorthand script into modern German. It took two more years just to be able to read Husserl’s shorthand. “It was 10 years before it could be published in 1973,” Kern said.

In Krattigen, Liu asked if the collection also existed in Chinese.

“No,” said Kern.

But Liu found the Chinese version on the internet.

It was published in 2018. The name of the editor was Ni Liangkang. Ni is a professor of philosophy in China. And he was one of Kern’s students.

Liu informed Kern about her discovery. She told him his work was circulating in China as a pirated copy. “He reacted like he was paralysed,” said Liu.

Kern got in touch with Ni. The elderly Swiss professor had recently had a visit from his former student. In 2019, Ni stayed with Kern in Krattigen, a year after he had published Kern’s work in Chinese.

Kern asked Ni on the phone: “Why didn’t you tell me?” Ni said it was all a misunderstanding.

“I couldn’t have any contact with him after that,” said Kern.

Laws were broken

“Ni Liangkang was in charge of translating Kern’s work in China,” said Liu. “Given his friendship with Kern, this is definitely odd. It would be normal for him to be the first to tell him.”

Kern hired a lawyer, who quickly discovered that laws had been broken – not just European laws, but Chinese ones too.

Translating and publishing foreign-language work requires advance permission, He Lei, a copyright expert from Beijing, told SWI swissinfo.ch: “If a book infringes copyright laws, the author, the publisher and even the printer are jointly responsible for the damage and are jointly and severally liable.”

Kern’s lawyer has demanded that the illegally published books be destroyed. And he has demanded a public apology from the plagiarist, Ni Liangkang.

But it’s not that simple – not for Ni. The risk of a loss of face looms large. His plagiarism is part of a major project by the National Social Science Fund of China. This foundation is financed directly by the central government. Its academic standards are high.

What is the foundation’s position on the accusation of plagiarism? SWI swissinfo.ch contacted the institution with a list of questions but received no reply.

In October 2022, a letter from the Chinese publisher arrived in Switzerland. The company said there had been a “big mistake due to the fact that the editorial department mistakenly assumed that the copyright had already expired.”

“We sincerely apologise to Mr. Iso Kern,” the letter says.

What is more, Kern’s book has since been withdrawn. The publisher agreed to pay Kern’s legal fees and compensation, and offered to name Kern as the editor in every new edition.

Reached by phone, Ni said: “This is a matter for the publishers – it has nothing to do with me.”

“I don’t think I will apologise to Iso Kern,” he added. “I think Iso Kern should apologise to me.”

Ni had maintained a teacher-student relationship with Kern for more than 40 years. The two stayed in close contact over the years, both academically and privately. Ni was one of Kern’s favourite students. “I would now like to ask Ni Liangkang to apologise. And to apologise publicly,” Kern said.

But that won’t happen.

Appeal to the Chinese president

This is where Xi Jinping comes in. The Chinese president is a great admirer of Wang Yangming’s philosophy – and Kern is the man who first made the great Wang accessible to the Chinese.

Xi has publicly declared his love for Wang. This has prompted Wang mania in China, as China Economy Online points out: “Only 10 years ago, Wang Yangming was not known to many.” But now he is a popular cultural icon in contemporary Chinese culture.

Wang (1472-1529), a universal thinker of the middle Ming dynasty, had a profound influence on the breadth of Chinese philosophy. His doctrine of the unity of thought and action is his best-known work. But his work can also be understood as an attempt to propose an individual’s personal morality as the primary route to social prosperity. This fits into Xi’s authoritarian system.

All kinds of events, including cultural tours and lectures, have sprung up around Wang Yangming; books about Wang are given prominence in bookshops.

Kern did pioneering work in communicating Wang’s ideas. Kern’s book, Das Wichtigste im Leben (The Most Important Thing in Life), uses the phenomenology of Western philosophy to interpret the teleology – the idea of purposefulness – of the Chinese thinker. Kern examines this thinking from a new perspective and analyses it in a new context.

That is the bridge he built.

Kern wrote to Xi Jinping: “I love China as I love my own fatherland, Switzerland. The fact that these unlawful acts were done by one of my Chinese students makes me very sad.”

Xi Jinping’s response is still pending.

Adapted from German by Catherine Hickley/gw. Edited by Balz Rigendinger.

Kern graduated from the University of Leuven in Belgium in 1961. From 1962 to 1971, he worked at the Husserl Archive in Leuven, editing and compiling texts on the phenomenology of inter-subjectivity from the shorthand notes left by Husserl. During this period, he also studied spoken Chinese.

In 1979 he gave up a full professorship to devote himself entirely to Chinese philosophy and went to China. By 1984 he had worked in Taiwan, New York, Nanjing and Beijing. From 1985 he taught Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism at the University of Bern, where he became an emeritus professor in 1995.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=cb688ed5)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.