How Switzerland tried to wipe out Yenish culture

For decades, Pro Juventute, a Swiss charitable foundation dedicated to supporting children and young people, systematically tore nomadic Yenish families apart. It separated children from their parents under its “Charity for the Children of the Road” project. How are these children coping today? Here is a look back at a dark chapter in Swiss history.

A pile of files sits on the dining table in Uschi Waser’s flat in Holderbank in canton Aargau. They are just a few of the many that Waser has accumulated over the course of her life. Waser is a member of the Yenish community, a nomadic people present in western Europe.

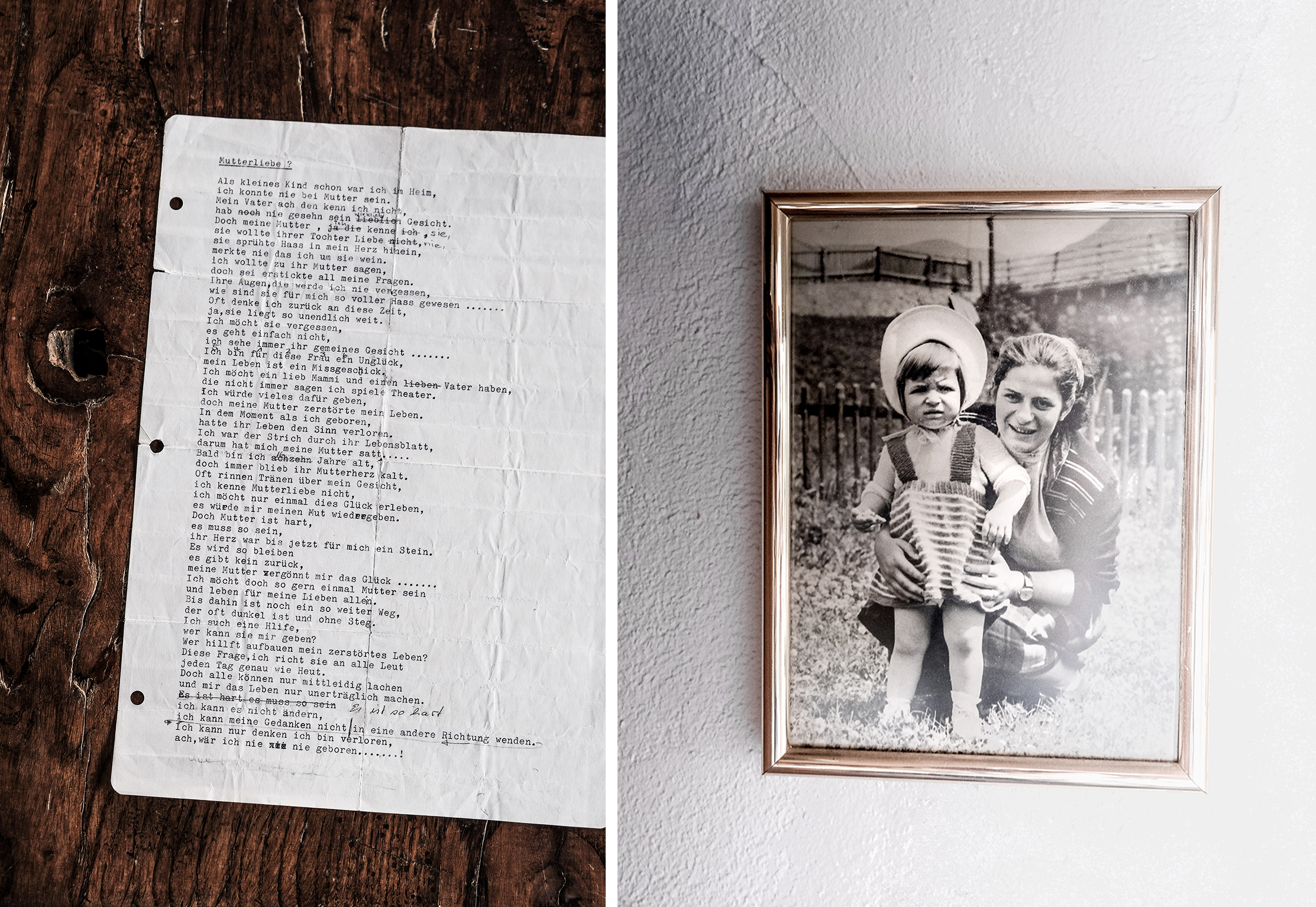

But her past has turned her into an archivist. Carefully, she takes a yellowing sheet from one of the folders and places it on the table. The paper looks as though it was once folded up very small, and it is slightly torn at the edges. “Motherly love?” is typed at the top in narrow letters.

“I wrote this poem when I was fifteen,” says Waser, who is now 71. “It’s hard to imagine. You can’t get much lonelier than that.”

At the age of 15, Waser had already experienced 25 different homes, clinics and foster families. She was taken away from her mother when she was barely 18 months old. After that, she never spent more than a few months at a time with her.

The initiative for her removal came from the “Charity for the Children of the Road” (Hilfswerk für die Kinder der Landstrasse), which was founded in 1926 at the initiative of Dr Alfred Siegfried of Pro Juventute. The aim of this “charitable” programme was to take Yenish children from their families to “settle them” and combat the “evil of vagrancy”.

Vagrancy was perceived not only as a cause of child “neglect”, but also as a danger to society. Between 1926 and 1973, when this so-called “charity” was dissolved, 586 Yenish children were torn from their families due to its interventions. Waser was one of them.

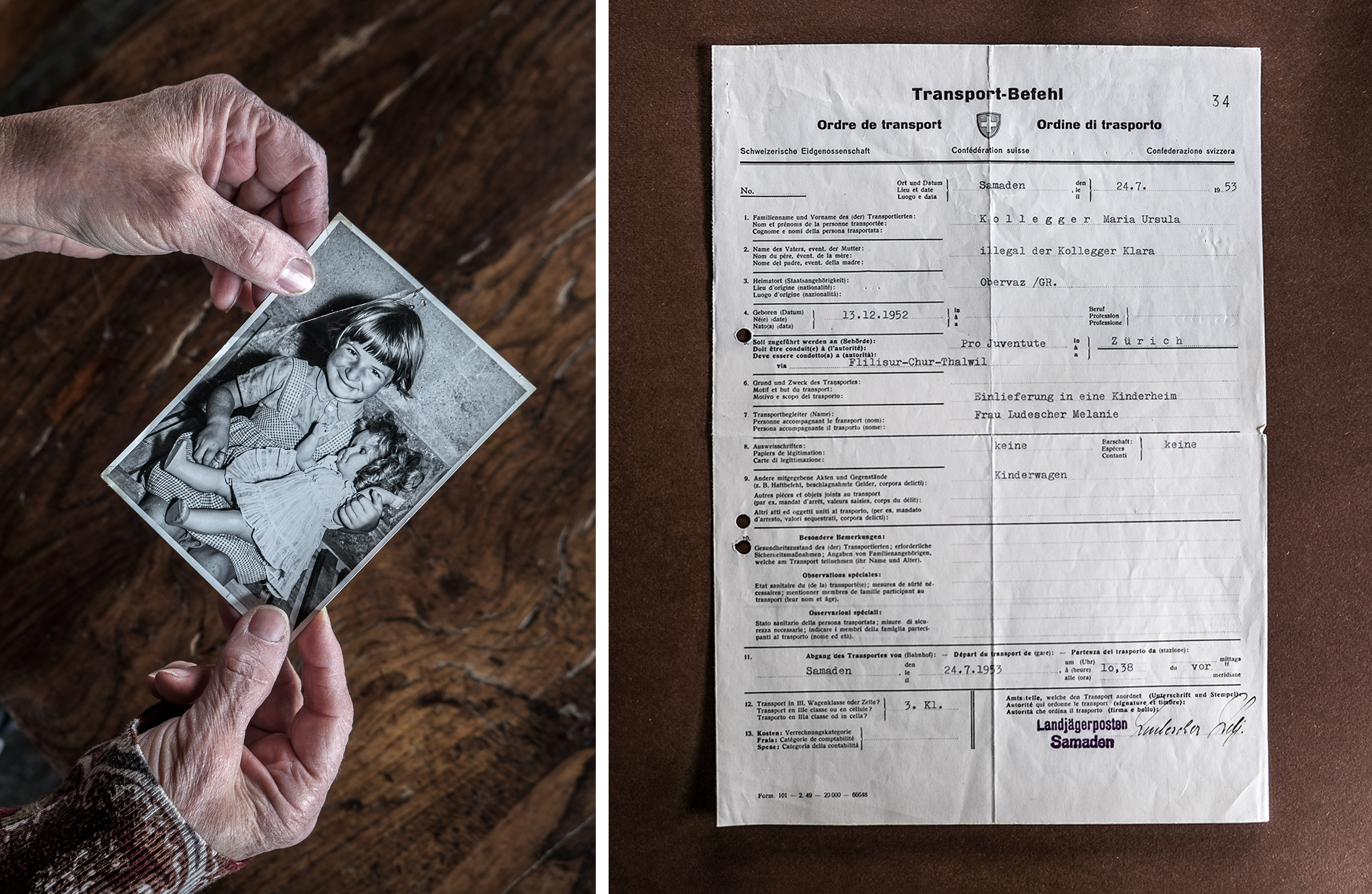

“My mother was an easy victim for Pro Juventute,” she says. Waser’s mother had herself been taken away from her parents by the charity as a child. As a single mother of four children, she was overwhelmed, and she beat them. “But she was also literally hunted down and driven into a corner by Pro Juventute,” Waser says. So in 1952, as soon as Waser was born, Siegfried did everything he could to gain custody of the girl. He wanted “at all cost” to prevent “a new line of vagrants” from emerging.

Waser was no better cared for in the homes to which he sent her than she was in her own, however. Punishments and beatings were routine. “I will never forget lying on a table as a child, being held down by two sisters while the third beat me with a carpet beater.”

For years, her mother tried to win back custody of her children. With no success. Waser was shunted from one home to the next. It was a fate she shared with many other “children of the road”. The result was upheaval and loneliness; even friendships were difficult. If two girls got along well together, they were separated as quickly as possible.

She did not find a loving home. The Erziehungsheim zum Guten Hirten (Good Shepherd Reformatory), where she spent several years, offered only “repression, unkindness, loneliness,” Waser says. “I would never have belonged there.” Every evening she prayed fervently “dear God, give me a father and a mother.”

“I prayed so much, enough for a lifetime,” she says.

The stigma of being in a care home

The “charity” drew on the eugenic and racist concepts of “vagrant research”. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Chur psychiatrist Josef Jörger was one of the first to compile lists of names and family trees of Yenish families to prove the genetic “degeneration” of “vagrant families”. This so-called Sippenarchiv (clan archive) was later used for psychiatric reports. Jörger also supported a policy of settling travellers and destroying their way of life, because he hoped this would improve the gene pool of these families. This view was taken up by the “Children of the Road” project.

In foster families, the children were to be raised to become “settled citizens”. However, most children grew up in care homes or institutions because too few foster families could be found. A childhood in care remained a stigma for those affected throughout their lives. “I always glossed over my biography,” Waser says. “I was afraid that I wouldn’t find work as a child from a care home.”

Life for anyone who was classified as “difficult to educate” by their guardian was particularly hard, because they had to go to a forced labour or work education institution, such as the Etablissements de Bellechasse in Sugiez, canton Fribourg. This prison, which rises above a bleak plain of endless vast fields, accommodated more than 100 “children of the road” who had never committed a criminal offence. This incarceration was justified as welfare. For the most part, the children in social care were housed separately from the juvenile offenders.

However, the agricultural work they had to do and the living conditions were almost the same as for the juvenile offenders. And society did not distinguish between the different reasons someone had been in Bellechasse. The general view was that “no one ends up in prison without a valid reason”.

The end of the ‘charity’ and the beginning of the search

As early as the 1940s, Yenish people turned to the media to complain about the charity’s practices. But they were given no credence until the 1970s, when a wide-ranging debate on care homes broke out. In 1972, the first articles appeared in the Beobachter newspaper. In 1973, 50 years ago, the Charity for the Children of the Road was dissolved under public pressure.

An era of political awareness and identity-building for the Yenish people followed. Numerous associations were founded. But above all it was a time of searching. Two or three generations of Yenish families had been torn apart and destroyed by the charity. People began searching for parents, siblings and lost children. Venanz Nobel, a Yenish man from Basel, remembers this time well.

“Back then, people turned up at stands every day and asked if anyone knew their family,” he says. “Every year, two or three people still contact me.”

His father, Sepp Nobel, was taken away from his parents as a child and had grown up with a foster family. In his father’s files, they later found a handwritten note from Siegfried. He wrote that he was conducting an experiment by taking this boy out of the travelling milieu and giving him to a settled alcoholic. Significantly, the Nobel family were considered “travellers” despite their permanent residence – because of their Yenish origins. That happened to many settled Yenish families at the time.

Sepp Nobel had a stroke of luck in this unfortunate situation. The “settled alcoholic” died, and his foster mother raised him lovingly. She also told him straight out that he was descended from “gypsies.” He wanted to know more. “Every year, my father travelled to Zurich to Pro Juventute and asked them to tell him who his parents and siblings were,” Venanz Nobel says. But they refused to provide information, and at some point his father gave up the search.

‘Deceitful, opaque and convenient’

It was only when Venanz Nobel became interested in his Yenish origins himself and began to investigate that he found what he was looking for. His grandfather had been dead for a long time; his grandmother had died recently. “At the funeral we met 50 new relatives, all at once,” he recalls. A short time later, Nobel bought a caravan and moved from one place to the next for 20 years. His father visited him, made his own friends, and at some point, also made peace with his Yenish identity, which he had previously seen mainly as a stigma.

Siegfried succeeded in preventing many marriages and determining the course his “wards’” lives took. The care files about the “children of the road” were harshly defamatory. At the age of 14, Uschi Waser experienced first-hand what effects this could have. She filed a complaint against her stepfather, who had sexually abused and raped her for years. The court acquitted him, however, based on statements and file entries about Waser that portrayed her as untrustworthy. “Basically, I didn’t stand a chance from the start,” she says.

During the trial, Waser tried to take her own life. “I remember it as if it were today,” she says. “I wondered who would put a flower on my grave. And I reached the conclusion that no one would.” Not her mother, who had sided with her husband in the trial. Nor the nuns who called her “naturally mendacious,” nor the guardian who only showed up after she had slit her wrists. The suicide attempt was taken as an admission she was lying and Waser was sent to therapy – not as a victim, but because she was deemed “pathological”.

She still finds it hard to talk about that time. When she saw her files in 1989, at the age of 37, she finally understood just how unlucky she had been. “I could never have imagined how cruel, how inhuman it was,” she says.

The Pro Juventute guardianship files were a bone of contention between the people they concerned, the cantons and the government for years, until they were finally handed over to the Federal Archives in 1986. The victims could see the files for the first time. For many, it was a difficult part of their search for family and identity. Nobel, for example, talks about his father’s feelings. “Even if you know the difference between facts and files, four federal files full of derogatory statements about you and your family don’t leave anyone indifferent,” he shares.

Without these files, Waser would be a different person today. But she would also never have gone public with her story. “I had to, otherwise I would have suffocated on it, killed myself or ended up an alcoholic,” she says. Now she is one of the few people affected who has told her story. Many others can’t, or don’t want to anymore.

As president of the Naschet Jenische Foundation (the name means “Rise Up, Yenish people!”), Waser is strongly committed to publicly confronting the past, has worked on a wide variety of projects, and has given countless interviews. But even she has never spoken to her daughters in detail about her past. Instead, she has developed her own strategies to come to terms with it. She has gained the upper hand over the files that for so long determined her life and controlled every step she takes. And she always keeps a door open for herself. “I always need an escape route, a ‘via d’uscita,’” she says. Her “via d’uscita” can mean a car of her own so that she can drive away at any time, or even just having enough cash on her to stay in a hotel.

What remains is her mistrust of authorities and the fear of having to go back into care. “I signed up for Exit, the assisted suicide organisation,” Waser says. “Now I just have to hope I don’t miss the right moment to jump.”

This is a shortened version of an article published in the magazine SurpriseExternal link.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.