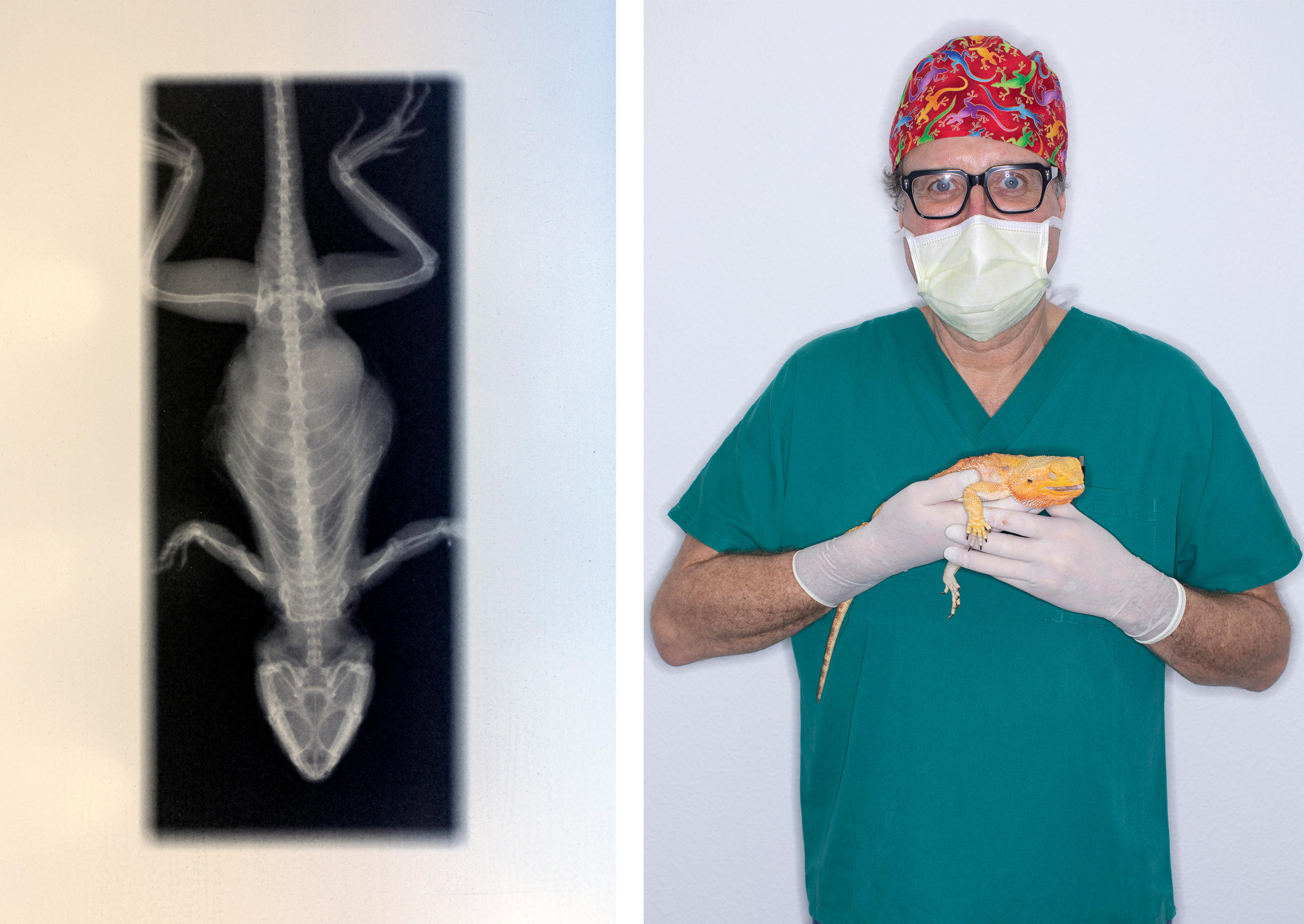

Meet Switzerland’s reptile whisperer

Paul Schneller is the first veterinarian in Switzerland to open a practice to treat exotic animals. A visit to his practice offers a glimpse at what it’s like to care for lizards and snakes.

The patient lies flat on its back on the operating table. The anesthesia has taken effect and Schneller is ready to make the first cut. But before he places the blade onto the scaly skin, he pauses.

“I don’t want to take any risks,” he whispers. “Maybe it would be better to let it go on living like this.”

The striped bearded dragon, a lizard native to Australia, has a tumour near its heart. After doing another palpation of the affected area, the veterinarian decides to go for it.

“Many pet owners come to me and ask me not to let their pets die,” he says. “So each time, I do my best.”

Prison time with an iguana

Snakes, lizards, turtles, chameleons, exotic birds and rodents: for nearly 20 years Schneller has been treating animals that would pose a challenge to most ordinary veterinarians, out of his practice just outside the city of Basel.

“There are only advantages to working with these animals. Unlike dogs and cats, they don’t bark or scratch,” he chuckles.

Sure, a lizard may be harmless, but what about snakes?

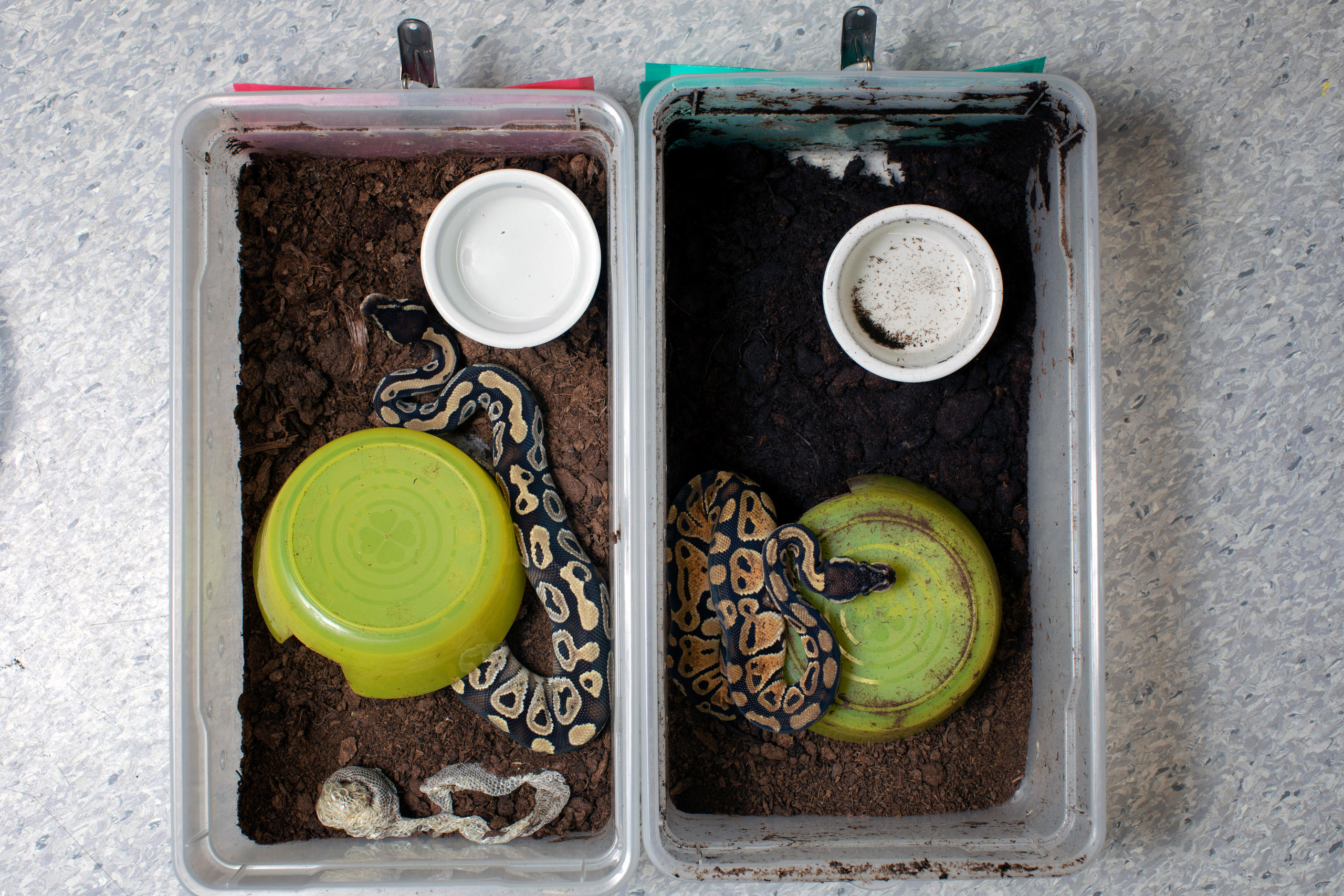

“I’ve been bitten by boas and pythons,” the vet admits. “I’m not so careful with non-venomous snakes.” But when treating a cobra or a viper, he says he is “focused like a runner before a race”.

Some of the most common ailments he sees are parasites and lung infections. Schneller, who also performs sterilisations and caesarian sections, says he sees an even more common problem.

“It’s people!” he declares. “Often the animal gets sick because it’s being kept in unsuitable conditions.” In his experience, an exotic animal doesn’t need more attention than a dog, but it does require more knowledge from its owner.

“The terrarium should reflect the same living conditions as the natural habitat when it comes to size, the light and humidity level,” Schneller explains. “The owner ought to know whether a lizard comes from a desert or a tropical forest.”

A reptile may not be able to wag its tail, but it can still form a strikingly strong bond with a person.

“It can sometimes be more intense than [a bond with] a dog,” he says. “Once I had a client who owned a green iguana and took really good care of it. But then he went to prison for several months. The lonely animal stopped eating. It probably would have died. But luckily we were able to get an exception so that the iguana could join its owner in prison.”

Knowing when a lizard is ill

Paul Schneller was right about the bearded dragon on his operating table. The tumour is sitting very close to its heart muscle. The smallest error during the operation could cost the reptile its life.

“Can someone help me with the gas?” he asks his assistants. The animal has started moving and needs another dose of anaesthetic.

Time and again Schneller has to improvise. There is neither medication nor instruments made specifically for these animals. To intubate the reptile, he now uses a part from a catheter devised for human use. Those who specialise in the treatment of exotic animals must make do with what’s available.

“After graduation, I worked in a horse clinic,” he says. “The atmosphere was very bad, almost elitist. That’s when it all hit me. I decided to take a different path.” After a 13-year stint working in the pharmaceutical industry that included opening his own drug research company, Schneller returned to his former passion for animals.

“I didn’t want to work with dogs and cats. At the time exotic animals were ‘in’ and when I came across a specialist shop, it occurred to me that I didn’t know anything about their health. It was above all an intellectual curiosity.”

Today Schneller is the go-to person for treating exotic animals, not just for the Basel region or Switzerland, but in neighbouring countries as well.

Flying foxes in the attic

“Finally!” he exclaims with relief. He places the roughly two-centimetre-long tumour, which he has removed from the bearded dragon’s chest, onto a piece of gauze. The intervention seems to have been a success. Yet, despite the application of a blockage, the wound won’t stop bleeding.

“If I don’t stop the bleeding, it will die on our hands. If this were a person, I would do a transfusion.”

For Schneller, it’s out of the question to leave an animal to its fate, even if it sometimes leads to minor tiffs with colleagues.

“The cantonal veterinarian called me once and told me I had to put down flying foxes that someone had illegally brought in from Australia. Of course I couldn’t kill the animals, simply because they were unlucky enough to have been caught by an idiot. After a heated discussion on the phone the veterinarian told me that if I could sterilise them and find them appropriate housing, he would make an exception.”

The human ego

The one-hour operation is over and the bearded dragon is returned to a plastic box. The bleeding has stopped and the wound is closed with four stitches.

“But that was a close one,” Schneller whispers to the animal.

For all his success and passion for his work, there is one painful reality that has accompanied him throughout his career: keeping a pet in a terrarium or cage is selfish.

“This is good only for the person, not for the animal,” he says. “That’s why I encourage all fans of exotic animals to at the very least keep their pets under the best possible conditions.”

He has tried to pass on this message in a book he wrote for pet ownersExternal link. In it he explains the biology and pathogenic properties of all known reptilian parasites. The book is considered a seminal work.

“This was one of my greatest endeavours – to make pet owners more competent [in caring for their animals],” he says.

Exotic animals in Switzerland

In Switzerland, residents are allowed to keep wild animals that don’t fall under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered SpeciesExternal link (CITES). Certain species, such as chameleons, poisonous snakes or giant snakes (with the exception of boas and pythons), are subject to a permit and owners must in addition obtain a certificate of competence (Art. 89 of the animal protection ordinance). Some cantons may also require pet owners to attend special classes and accept home visits by the cantonal veterinarian. A person who is no longer able or willing to take care of an exotic pet cannot for obvious reasons set it free in the wild but must instead contact specialised centres run by associations of exotic animal lovers.

Adapted from German by Geraldine Wong Sak Hoi

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.