All aboard for Turkey’s elections

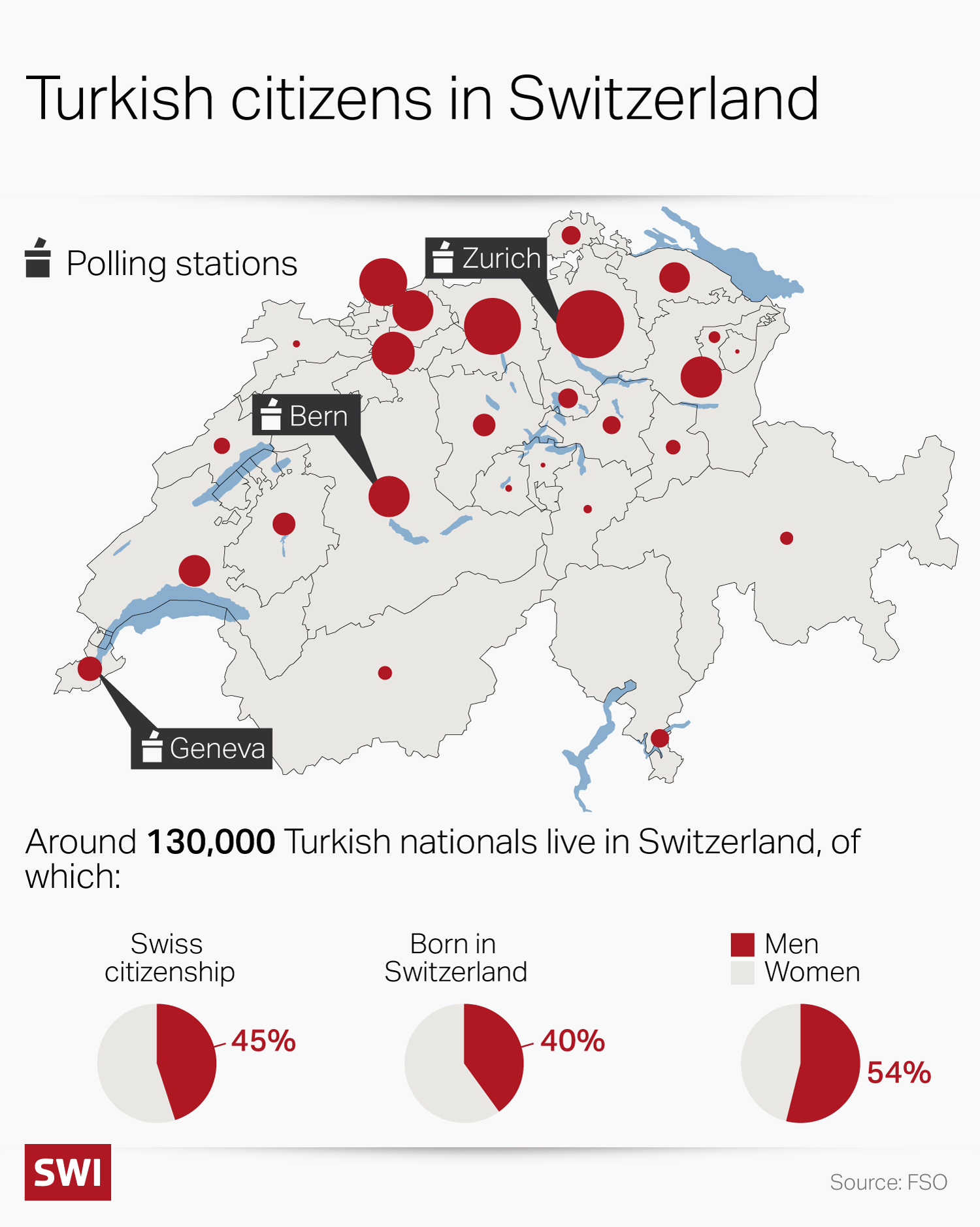

The Turkish republic will be a hundred years old this year. It is facing a fateful election. Over 100,000 of the 64 million voters live in Switzerland. SWI swissinfo.ch gauges the mood of the Turkish diaspora.

The scene could hardly be more Swiss. It’s Sunday morning in the community of Münchenstein near Basel. Over 100 people have gathered for brunch at a local inn. There is the sound of laughter. Children play outside in the sun. A bus with the destination-sign “special” is parked out on the car-park.

The event has been organised by Elif Yıldırım. She used to be the editor of a local Turkish newspaper. Yet this Turkish-Swiss dual citizen is not allowed to vote in the upcoming Turkish parliamentary and presidential elections on May 14. “I lost my vote due to a court case involving me as a journalist,” she told SWI swissinfo.ch.

So she does what she can for her Turkish homeland in Switzerland. The Sunday brunch in the inn has been organised to bring aid to the victims of the devastating February earthquake that crushed thousands of buildings and killed 50,000 people in Turkey.

Yıldırım no longer works as a journalist, but as a social worker attached to a school and as a nurse with her own business. She also actively supports Swiss politicians with Turkish roots. These are gradually taking a greater role in Swiss political life. One of them is Green Party parliamentarian Sibel Arslan. Others are the Social Democrat Mustafa Atici and Liberal Green Bülent Pekerman, who is currently president of the cantonal parliament in Basel City.

Yet neither the effects of the earthquake nor the influence of Turkish-born politicians in Switzerland dominate the conversation over brunch. “I am here because of the elections in May,” says 16-year-old secondary student Lorin Toptas. “The future of our country is at stake.”

Indeed, at stake in Turkey’s elections is whether autocratic President Recep Tayyip Erdogan can hold onto power in this NATO-member nation straddling Europe and Asia, or whether there will be a change of government. Erdogan has spent two decades in power, first as prime minister and then as president.

Like Yldirim, Toptas has no right to vote on account of her young age but she cares deeply about what happens in Turkey. “I have relatives in Turkey and friends and acquaintances in Switzerland who get to vote for the first time this time around,” she says.

To show her support, Toptas boards a bus making that “special” trip from Münchenstein to Zurich. There will be frequent stops along the way to collect people who want to go to the Zurich polling station. It is one of the three polling stations in Switzerland which are open for nine days to accommodate the 100,000 Turkish voters living here.

In Turkey, 60 million voters are eligible to weigh in on the fate of their country on May 14. If none of the six candidates running for president gets more than 50% of the vote, there will be a run-off on May 28. In that case polling stations in Switzerland will open again for another five days (May 20- 24). Globally, there are a potential 3.5 million voters in the Turkish diaspora. They can vote phsyically at one of the 177 polling stations set up in 74 countries. And they can also choose freely where they want to vote, thanks to an electronic electoral register.

The large Turkish diaspora in Europe had considerable weight in the last elections. In 2014, Erdogan had given them the right to vote without returning to Turkey to do so. In recent elections and referendum votes in Turkey – the constitutional referendum of 2017 and the parliamentary and presidential elections of 2018 – there were notable variations in the political tendencies of Turks living abroad. In Germany, almost two-thirds favoured the right-wing conservative message of president Erdogan, while in Switzerland almost two-thirds sided with the anti-Erdogan opposition.

Özgur Özvatan is a researcher on migration who heads the department of integration research at the Berlin Institute für Migration Research of the Humboldt University. For him, these varied trends have to do with people’s province of origin in Turkey.

“In Germany, many of the Turkish voters come from the traditional and usually right-wing conservative provinces in the interior of the country. The election trends in Switzerland lead one to suppose that the Turkish emigration there has been mainly Kurdish or else from the western coastal region, which traditionally favours the Kemalist and social democratic CHP [Republican People’s Party],” Özvatan told SWI swissinfo.ch.

The first voter to turn up at the polling station at the exhibition grounds in Zurich before it opens is Baris Ilhan. He travelled from Buchs in canton Aargau with his family this morning. Why? “Last elections we had to wait a long time in a queue, but this time we are first in line.” Unlike most of the people taking the chartered bus from Basel, Ilhan intends to vote for Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), again.

“In a country like Turkey you can’t have a democracy like here in Switzerland,” Ilhan believes. “It takes a strongman like Erdogan, not a weakling like Kilicdaroglu.”

As in 2017 and 2018, Ilhan represents a minority view in Zurich and Bern. In Geneva, though – the third polling station in Switzerland – at the last elections, majorities seemed to favour the course set by Erdogan. That came as a surprise, since many of the Turks in the Geneva region come from provinces where people traditionally favour secularist and Kurdish parties. There is a reason for this, however.

“In this polling station we get many voters from across the border in France,” explains Ipek Zeytinoglu Özkan, the Consul-General of Turkey in Geneva. Along with her colleague, Vice-Consul Metin Genc, she oversees voting at the Geneva exhibition grounds, which is only a short distance from the airport and the French border. Many of these voters from France turn out to be conservative Sunni Muslims, who have been particularly courted by president Erdogan and the AKP in this election too.

The holding of serious well-organised elections where the result can be accepted by the losing side is “one of the few permanent achievements of democracy in Turkey,” according to Swiss historian Hans-Lukas Kieser, who currently teaches at the University of Newcastle in Australia.

This has been the case even where repression and unequal resources have made the election unfair. At the end of the Ottoman Empire, which for centuries included large parts of the Eastern Mediterranean, north-east Africa and the Middle East, there had been “repeated encouraging attempts and proposals for a liberal Turkish state with a constitution”, as Kieser notes. But nationalistic and authoritarian forces overwhelmed them again and again.

The Treaty of Lausanne and the new Turkey

In a recently-published book* historian Hans-Lukas Kieser shows how the Lausanne peace conference a century ago gave birth to a Turkish state which mostly denied the rights, history and culture of non-Turkish populations in the country. The conference held on the shores of Lake Geneva lasted eight months. It showed how considerable the relations between Switzerland and Turkey already were at that time. This aspect is apparent from a new exhibition in the Historical Museum of Lausanne** curated in part by anthropologist Gaby Fierz.

With the end of the First World War, refugees as well as government delegations found their way in special trains from Turkey to the shores of Lake Geneva. “Swiss capital and know-how played an essential role in building up the railway infrastructure between Europe and the Middle East,” Gaby Fierz told SWI swissinfo.ch. After the Lausanne accords were signed on July 24, 1923, the new Turkish republic – officially proclaimed on October 29, 1923 – adopted Swiss civil and commercial law. Nestlé opened its first chocolate factory in Turkey in Istanbul, where the Swiss multinational had had a branch since 1878.

*Kieser, Hans-Lukas. 2023. When Democracy Died: The Middle East’s Enduring Peace of Lausanne. Cambridge University Press.

**Frontières, Le Traité de Lausanne 1923-2023. Musée Historique Lausanne. Open April 27 to October 8 2023. Parts of this exhibition will be shown from August 14 on at the Polit-Forum in the Käfigturm in Bern.

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.