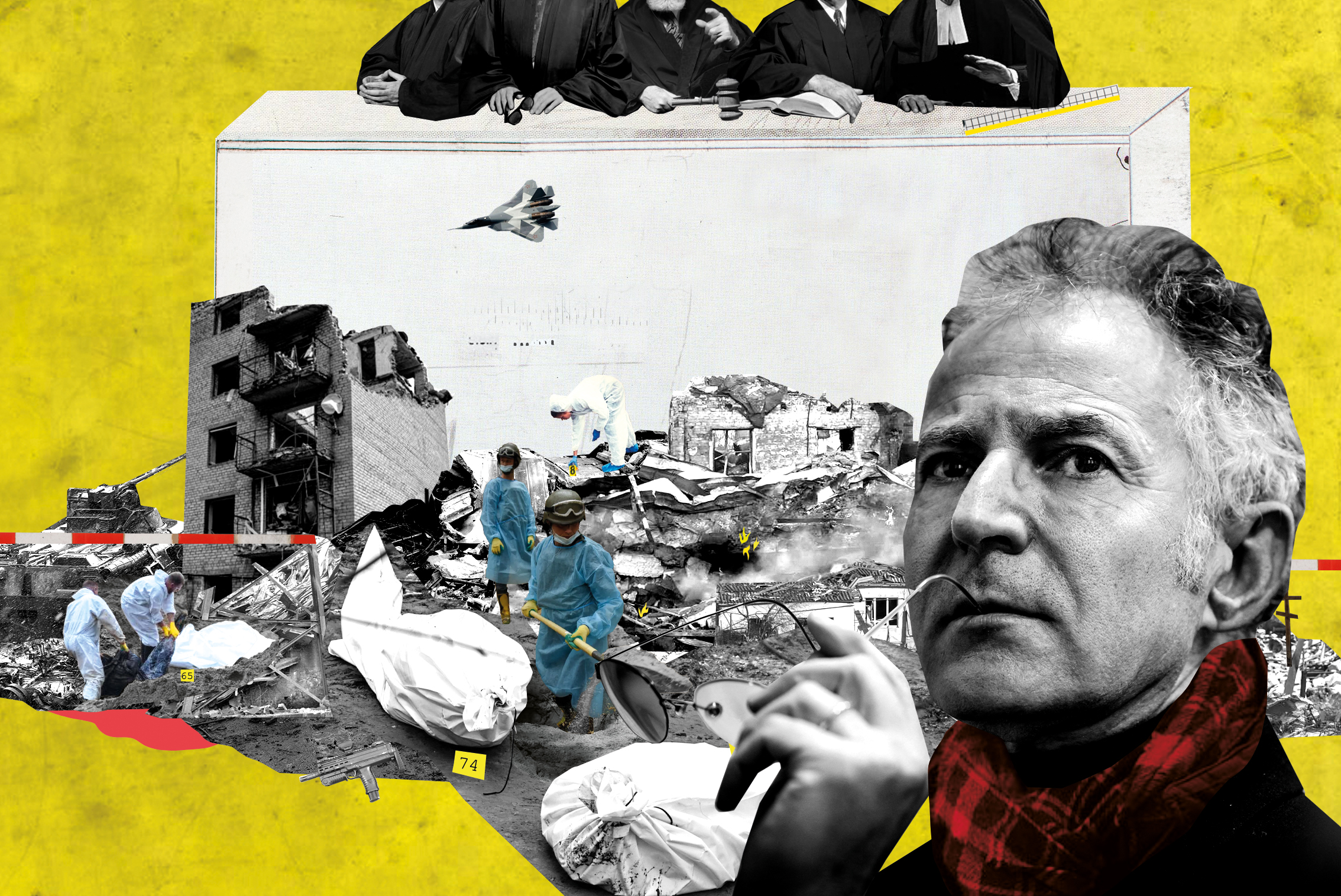

François Zimeray: ‘Can real justice exist without peace?’

Ukraine will have to wait for justice. But is it possible to hope for peace without justice? How can a truce be brokered with an enemy responsible for terror and murder? François Zimeray, lawyer and former French diplomat, considers these questions.

Zimeray practises law in Geneva and Paris and is also a lawyer for the International Criminal Court (ICC). He was formerly the French Ambassador for Human Rights and served as a member of the European Parliament. He has worked on cases involving child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the genocide committed by the Khmer Rouge. In 2015, after the Charlie Hebdo shootings in Paris, Zimeray survived a terrorist attack in Copenhagen, where he was the French ambassador.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Switzerland and other countries have condemned the atrocities committed by the Russian armed forces in Ukraine. The EU has emphasised that the Russian authorities are responsible for these crimes. What should be done now that Ukraine is calling for justice?

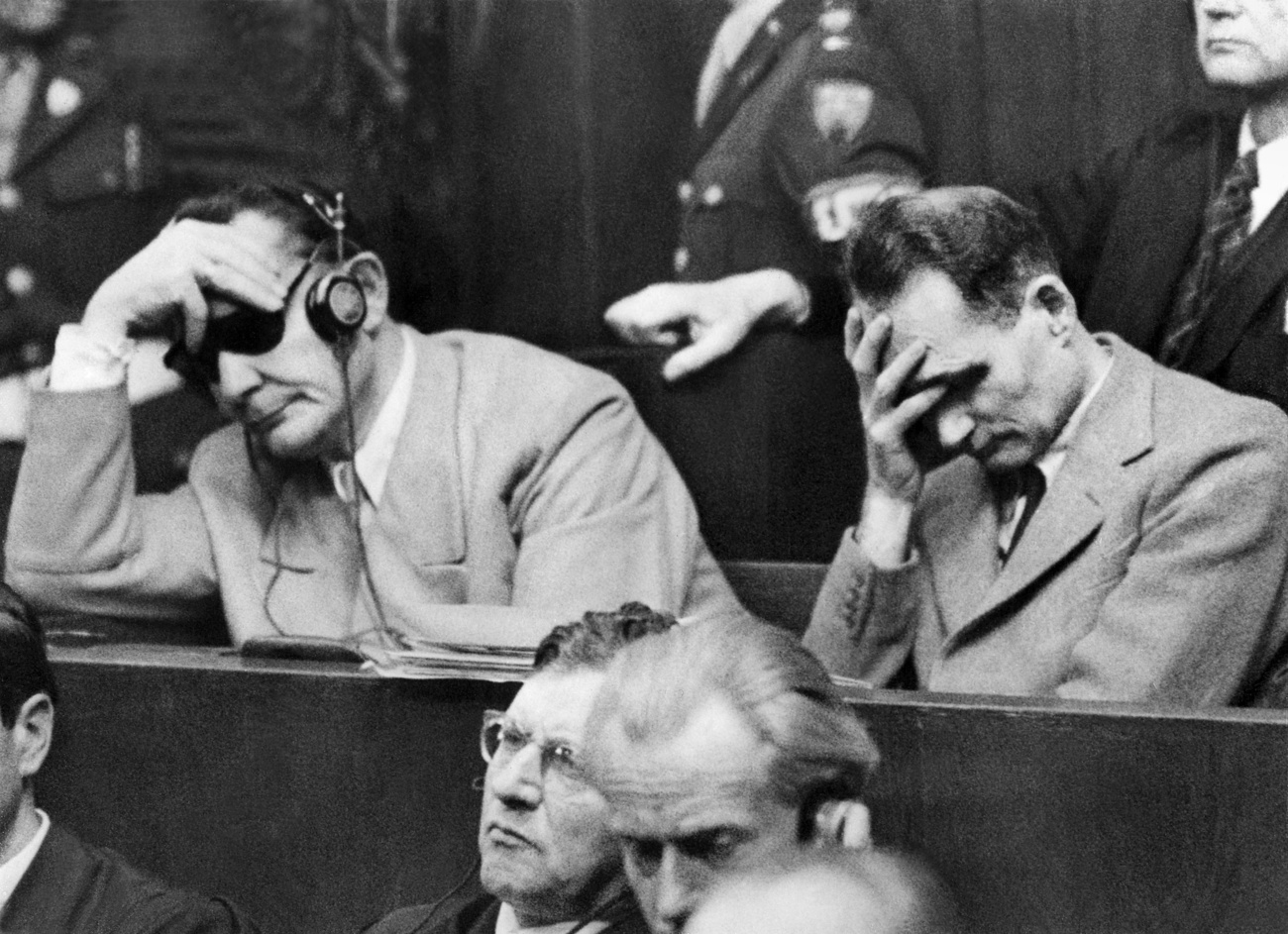

François Zimeray: History teaches us that there’s a time of conflict, then a time of peace-making, and finally a time for justice. As we witness the atrocities [in Ukraine], as blood is still flowing, we all feel a need for justice – it’s hard to accept our own powerlessness to stop the crimes. But we have to face the facts: now is not the time for justice. The moment for the law will certainly come, but when? And in which court? The ICC has the most universal jurisdiction. But countries whose authorities risk being pursued by the ICC have not adopted its Rome Statute, which created the Court. Russia is not party to the Rome Statute – nor, by the way, is the United States – so it’s hard to imagine that Moscow would now willingly accept a special tribunal, a new Nuremberg Trials. In other words, Russia is no more likely to recognise the legitimacy of a “21st-century Nuremberg” than that of the ICC. Which raises the question: is there a way, despite this, to bring these crimes to justice?

In the history of humanity, the Nuremberg Trials represent immense progress, but the legitimacy of a court must be recognised by everyone – victims and accused. Since Nuremberg, international justice has made significant advances in guaranteeing a fair trial and, importantly, curbing the impression that victors impose the verdicts.

SWI: Didn’t people question the legitimacy of the Nuremberg Trials at the time?

F.Z.: Yes, of course the question came up. And it did again much later, notably in France during the trial of Klaus Barbie [head of the Gestapo in Lyon, convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life in prison in 1987]. Contesting the legitimacy of judges can be a line of defence, but it lacks honour or effectiveness. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Nazi defendants had little choice. Today, the legitimacy of a special tribunal would be bitterly debated. There’s also the issue of Russia’s veto power in the UN Security Council, where it would be supported by China. Any UN initiative would face that obstacle.

SWI: How can these crimes be judged without the legal process being contested?

F.Z.: The idea of justice in the near future is obviously appealing, but is it likely or realistic? What seems certain to me is that Ukraine has legitimate grounds to try these crimes, and international law allows it. Since the victims are primarily Ukrainian, the country’s courts indisputably have jurisdiction. Ideally, Ukrainian courts would act with the assistance of the UN and maybe the technical support of the ICC.

SWI: But beyond that, who has legitimacy to try war criminals and under what conditions might a trial be accepted?

F.Z.: Ideally, if a case can’t be referred to the ICC, an ad hoc tribunal would be established, as has been proposed. It would have clear benefits legally but also for history. But again, would it really be feasible without international consensus? Ultimately, I think Ukrainian courts are best placed to try the crimes: they have the information and the names, they know the language, they have a good grasp of the facts, the victims are local – it all happened on their soil – and, above all, they have perfectly integrated the requirements of a fair trial. Their legitimacy is indisputable. If Ukraine issues an international arrest warrant, the person in question will no longer be able to travel beyond Russia’s borders.

There’s another option that might seem unimaginable but could become a reality: the Russian justice system. At some point, the people who committed these crimes will have to answer not only to Ukrainian courts but also to Russian ones, which have jurisdiction too. This presupposes, of course, a regime change in Russia, but isn’t that brewing? It’s clear that things are shifting. Everything I’ve seen and heard throughout more than 100 missions around the world leads me to believe that even the most opaque and closed regimes contain fracture lines, which are as deep as they are hard to detect.

There are obviously people in the Kremlin who don’t agree with Putin. We’ve seen the military mobilisation provoke unbelievable reactions among a segment of Russian society – and the courage of journalists who are starting to express themselves. Thousands or even tens of thousands of people have died. And how many grieving families and people affected directly or indirectly are there? At some point, they will break their silence.

SWI: You talked about a time for justice. Why should justice have to wait?

F.Z.: There can be no durable peace without justice, but can real justice exist without peace? You can’t go from conflagration and tears to court without some kind of interlude. An inquiry has to unfold; weapons must be laid down and victims must testify. Faced with atrocities, we wish for immediate justice, but justice requires serenity to refrain from revenge. How could parties conceivably work out a ceasefire if it immediately resulted in one side going to prison? Diplomats are deeply familiar with this kind of paradox.

SWI: Isn’t there a risk of impunity?

F.Z.: It’s an awful but real risk. In fact peace is often negotiated on condition of amnesty. This concept has become unbearable.

SWI: Do you think the Russian population will ever realise what really happened in Ukraine if the criminals aren’t tried?

F.Z.: It’s primarily a question of freedom of the press and education. Until now, Russians have really only known nationalism, propaganda and denial. They’re caught up in dangerous victimisation, and we’re witnessing the results. About ten years ago during a mission to Russia, I was struck by the fact that the officials and the military seemed convinced that NATO’s only goal was to jump down their throats. We’ve seen where this kind of delusion leads…

SWI: Neither Switzerland nor France uses the term ‘genocide’ to describe Russia’s actions, but Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky does. Why?

F.Z.: I understand why Ukrainians use the term. If I were in their place, I might say the same thing. But in law, words have to describe situations as precisely as possible, and they have consequences. The Russian army and its commanders are committing war crimes and crimes against humanity, but the term “genocide” describes the general mass elimination of an ethnic or human group.

SWI: If there were a “Nuremberg Trials 2”, would Russian propagandists be among the accused?

F.Z.: Instigators and accomplices are punished as criminals, and it’s clear that those who fanned the flames of resentment and paranoia bear considerable responsibility. This makes me think of what [Holocaust survivor and political activist] Elie Wiesel said: “The Shoah didn’t start with the gas chambers; it started with words.”

Edited by Balz Rigendinger. Translated from French by Katherine Bidwell/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.