Why Russia sees satanic powers at work in Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has created a massive rift within Christian Orthodox communities. In an interview, theologian Stefan Kube, editor of a Swiss journal on religion, explains why.

The war in Ukraine has been raging for almost a year, and Russia’s justifications are becoming increasingly shrill: initially the Kremlin used terms like “denazification” and “demilitarisation” for its war propaganda, but more recently, openly genocidal language has been directed at the Ukrainians.

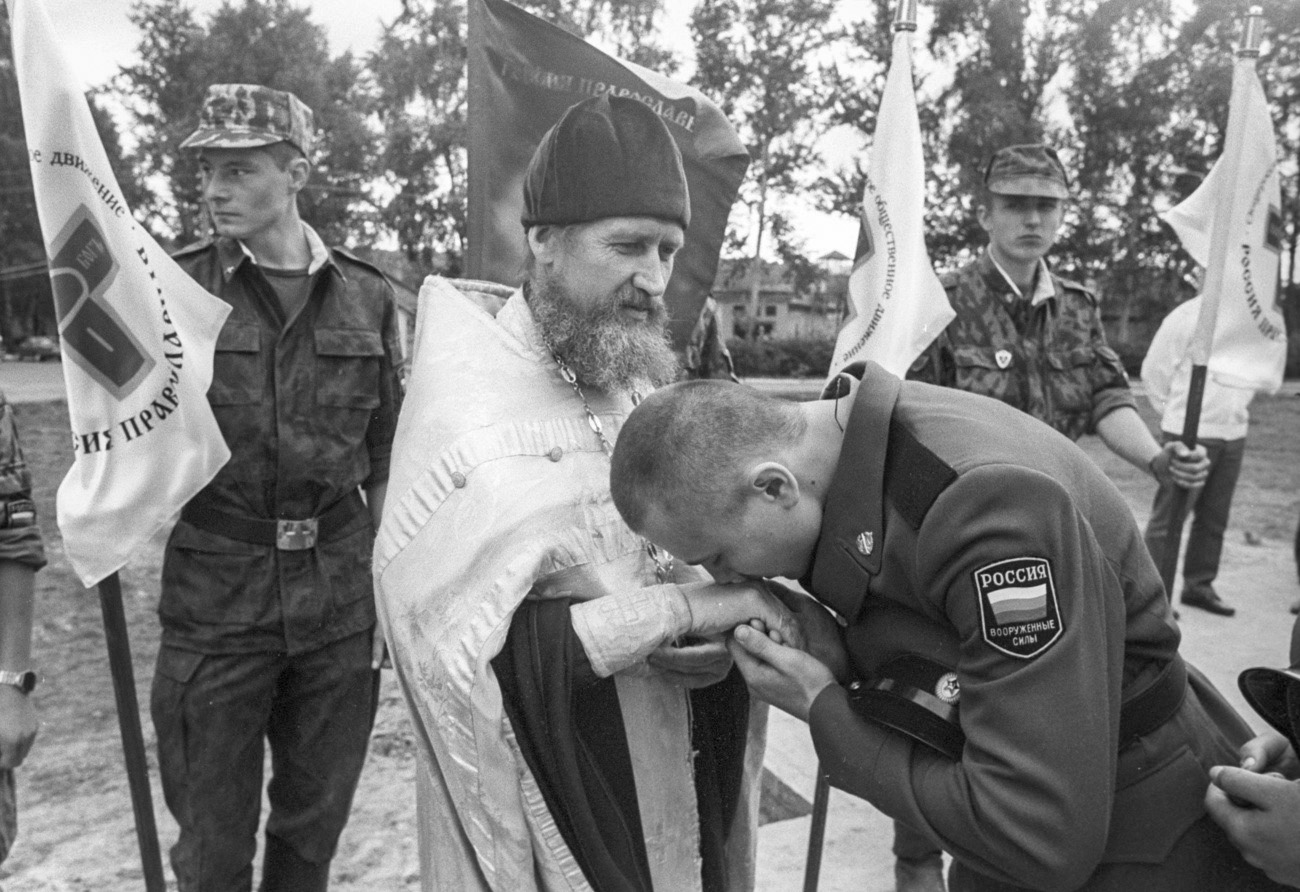

The narrative of the Russian Orthodox Church has also become increasingly apocalyptic as clerics claim that satanism is widespread in Ukraine and that Russian soldiers who fight in the war can hope for absolution. Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has taken on a metaphysical undertone which has led to fierce criticism within Orthodox communities and a seemingly insurmountable split.

Stefan Kube is a theologian and institute director of the G2W Institute’s Ecumenical Forum for Faith, Religion and Society in East and WestExternal link. The institute publishes the monthly specialist journal Religion & Society in East and West (which Kube edits), supports social projects and serves as a consultant on questions concerning the coexistence of European religious cultures.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Recently Russia has called for the ‘desatanisation’ of Ukraine, talking of a Holy War. To what extent is this a religious war?

Stefan Kube: Since the beginning of the invasion the Russian Patriarch Kirill has preached in his sermons that Russia had to defend itself in Ukraine and had to fight “aggressive Western values”, above all secularisation, pluralism and the decline of conservative values.

For the Russian Orthodox Church as well as the Russian leadership the war in Ukraine is a defensive war and the people of Ukraine have been seduced by Western “forces of evil”. Such a narrative serves the theological-ideological justification for the war and allows Kirill to call it a Holy War. It’s not a question of a conflict between religious communities – the war in Ukraine is not religious – it’s a question of theological propaganda.

SWI: To what extent are the actions of church and state coordinated?

S.K.: I give you an example: during his traditional Russian Orthodox Christmas message, Patriarch Kirill called on both sides of the war in Ukraine to observe a Christmas truce on January 6 and 7. A few hours later, [Russian President] Vladimir Putin proposed the same, which suggests that it must have been previously agreed. However, the Christmas truce never happened. It was a tactic to demonstrate that Russia wanted de-escalation and peace while the Western “forces of evil” sabotaged their wish.

Over the past few years, state and church have become close allies when it comes to pursuing the same goals. For example, toughening the laws against so-called homosexual propaganda is one such goal.

SWI: The proximity of state and church is quite common in orthodox countries. Is Russia a special case?

S.K.: It’s true that the relationship between state and church is very different in Western countries. In the Orthodox church, the concept of “symphonia” – a harmony between state and church – still prevails. This dates back to the Byzantine Empire.

However, it has always been more of an ideal and has never in history been realised in an Orthodox country. The Russian Constitution declares Russia a secular state without religious affiliation. But since Putin and Kirill have been in power, the alliance has become stronger, even though the state clearly has more power.

More

Russian Orthodox Church Patriarch Kirill spied on Switzerland: Swiss media

SWI: What’s Kirill’s role in all this? There have long been rumours that he used to cooperate with the Russian secret service.

S.K.: There is some evidence that Kirill used to work with the Soviet Intelligence Service KGB where Putin was also a member. But at the moment it’s impossible to reconstruct his involvement as the KGB archives were closed again in the 1990s. This was partially due to pressure from the Russian Orthodox Church, which was struggling with internal disputes.

Some people wonder whether Kirill truly believes what he says and preaches in public. We cannot look into his head, but his messages have been detrimental to Ukraine, and he needs to be judged on that.

Numerous religious leaders and theologians from the Orthodox and other churches have called upon him to distance himself from the war, but he’s done the opposite. This has led to tensions within the church. Some Ukrainian Orthodox followers who felt affiliated to the Moscow Patriarchate have now broken with Russia, and we see similar developments in other countries. More and more people are moving away from the church, a trend which has partially been instigated by the state. This trend is currently obvious in the Baltics.

SWI: The ecclesiastical conflict in Ukraine has been going on for some time. Can you put it into perspective?

S.K.: The religious landscape in Ukraine is very complex. Since the country gained independence in 1990, different lobbies have developed within the Orthodox community. There is a strong lobby that pushes for independence or at least for more autonomy from the Moscow Patriarchate. In Soviet times, all Orthodox believers belonged to the Russian Orthodox Church, some of them were forced to join after the Second World War – first and foremost the followers of the Greek Catholic Church in western Ukraine.

Over time, three Orthodox churches have emerged. The largest church was close to the Moscow Patriarchate but was internally autonomous; the other two churches sought independence as they felt ecclesiastically and politically oppressed by Russia and wanted their own national church.

Kirill (Vladimir Mikhailovich Gundyayev) became the Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia and Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church on February 1, 2009. He is considered conservative and a close ally of Vladimir Putin. Some say he is affiliated with the secret service and the military. He has come under fire for his personal wealth. In 2009, a photo that was doctored to airbrush out an expensive Swiss watch caused a furore.

10/ The $30K watch, donated by an anonymous benefactor, caused controversy after a clumsy attempt to remove it from a photo – it was airbrushed out but the photo editor forgot to remove its reflection in a polished table top. Several leading ROC clergy have had similar scandals. pic.twitter.com/Kak7HBXk8VExternal link

— ChrisO_wiki (@ChrisO_wiki) July 8, 2022External link

These two churches united in 2018 to form the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church, on the other hand, was always part of the Moscow Patriarchate until it broke away from Moscow in May 2022 because Kirill failed to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

SWI: Do you think the war has caused some people to change church?

S.K.: I’m sure a lot of people have changed to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, but it is still smaller when it comes to infrastructure and the number of clerics. Some members of Ukrainian society and politics view the Ukrainian Orthodox Church with suspicion. Breaking away from Moscow is now a question of national loyalty, even though the Ukrainian Orthodox Church has clearly positioned itself against Russia’s invasion.

SWI: Ukraine is also the scene of a major conflict within global Orthodoxy. Is this a geopolitical problem?

S.K.: On the one hand, we have the Moscow Patriarchate, which is the largest and most populous patriarchate in the Orthodox world. On the other hand, we have the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, which played a significant role in the formation of the new Orthodox Church of Ukraine which enjoys a historic primacy of honour within Orthodoxy. The Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople has long been urged by Ukrainian politicians and believers to intervene in the ecclesiastical conflict and give Orthodox followers in Ukraine their own independent church and let them choose their own leaders.

Finally in 2018 Bartholomew gave the Orthodox Church of Ukraine the ecclesiastical autonomy it wanted, which led to a break with Moscow. Following this move, the Russian leadership cut all ties to Orthodox churches that have recognised Ukrainian independence; however, not all of them have.

The relationship between Moscow and Constantinople had already turned sour: Moscow has been more conservative to adopt Western values while Constantinople has been quick and more progressive to do so.

We are faced with a deadlock: the two largest Orthodox churches no longer talk to each other, which is a problem for Orthodoxy. There have been mediation attempts, but to no avail.

SWI: Some say there is schism within the Orthodox Church. Would you agree?

S.K.: Yes, in fact there is schism no matter whether it can be theologically defined as such or not. There is a significant rift within the Orthodox Church which is also a personal dispute between Bartholomew and Kirill. I doubt they will ever talk again.

We must not forget that all this only concerns church leaders, and that theologians and the followers of both churches still talk to each other and are critical towards the leadership of both churches. At the end of the day, it’s all about church politics.

Edited by Balz Rigendinger. Translated from German by Billi Bierling/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.