How a teen is taking on antibiotic resistance

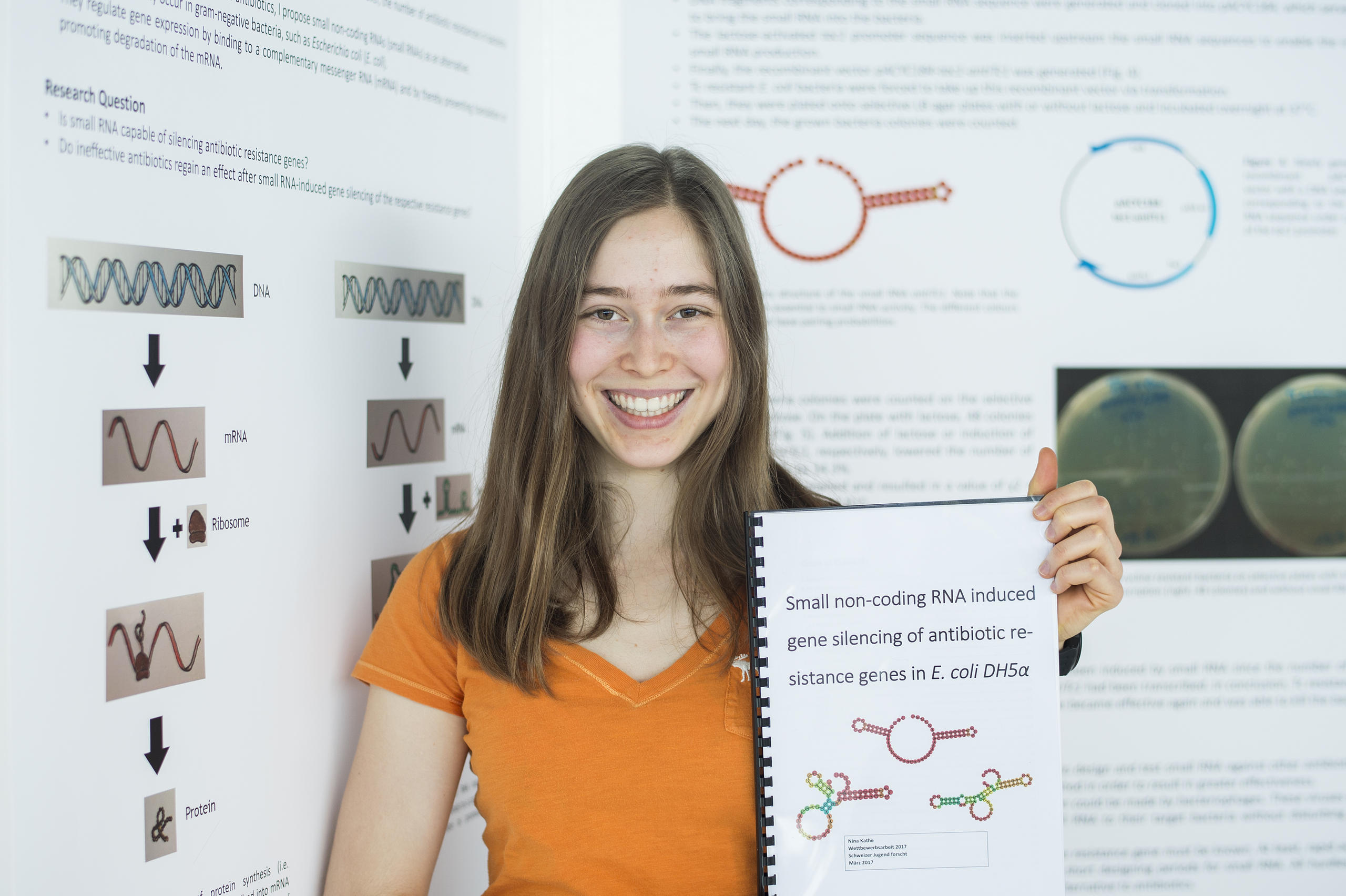

Nineteen-year-old Nina Kathe has just begun freshman classes at the University of Zurich, but she’s already the author of award-winning research into a global public health concern.

Given the two prestigious honours it has earned, you might think Kathe’s research project on antibiotic resistance in E. coli bacteria was the result of a research grant or scientific collaboration. But in fact, she conducted the experiment herself on her home computer and in her biology classroom in the northern Swiss canton of Aargau, as part of her secondary school final examination.

“When I proposed my idea to my biology teacher, he looked at me strangely and said I could try it, but that it sounded really utopian and not to be disappointed if it didn’t work out,” Kathe recalled to swissinfo.ch.

“I was supposed to do my final project in a group of two, but I convinced the teachers that this would be too complicated. So, I dug deeper and read many articles and searched through many databases. Then, I set up the experiment and performed it,” she says.

Upon finding that her school’s biology class didn’t have all the equipment she needed, Kathe obtained permission to use lab space and equipment at the University of Zurich, where she is now a first-year student of biomedicine.

In the coming months, Kathe will have to juggle her full course load with a weeklong visit the renowned European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) at the University of Heidelberg, Germany. The trip to EMBL is an EIROforumExternal link special prize, which Kathe won for her project in September at the 29th European Union Contest for Young Scientists (EUCYS)External link in Tallinn, Estonia. Her participation at the EUCYS event was itself an award for the same work, which she won earlier this year at the annual Swiss Youth in Science (SJF)External link national competition.

“Nina Kathe has addressed a vital question of modern societies, namely the antibiotic resistance of pathogenic bacteria,” says Hugo Stocker, a researcher group leader in molecular systems biology at the Swiss federal technology institute ETH Zurich, who judged Nina’s work at the EUCYS competition.

“Her work evidences both her enthusiasm for biomedical research and her astounding maturity. It is at a level far above what can be expected from a [secondary school project].”

Bamboozling bacteria

The goal of Kathe’s experiment was to see if molecules called small non-coding RNAs could shut down the activity of genes in E. coli bacteria that produce resistance to the antibiotic tetracycline. To do this, Kathe developed an artificial RNA sequence aimed at interfering with the activity of tetracycline resistance genes in E. coli. She found that in the presence of these specially designed RNA molecules, many of the bacteria lost their resistance to tetracycline, and were successfully killed when exposed to the antibiotic.

Because RNA molecules tend to be unstable in a laboratory setting, Kathe managed to engineer the E. coli’s DNA so that the bacteria would produce the modified small RNAs themselves – ultimately causing their own demise.

“That was maybe a bit mean if you want to put it that way, because the bacteria themselves produced the RNAs that would ensure the antibiotics could kill them,” Kathe laughs.

While the experiment was largely successful in terms of knocking down bacterial resistance to tetracycline, Kathe emphasises there is much work left to be done.

“It’s not a substitute for the antibiotic itself, but it makes the antibiotic effective again,” she explains, noting that the efficiency of the process needs improvement. She says she would like to repeat it to see what’s happening inside the bacterial cells on a molecular level.

“If I can improve the method and learn what’s essential to shut down these resistance genes, then the next step would be to make the transition to in vivo experiments, for example in a mouse model,” she says.

She hopes that one day the method could be used to develop a drug for humans that would re-establish the effectiveness of antibiotics against bacteria that have become resistant.

WHO antibiotic resistance quick facts

– The World Health Organization (WHO)External link defines antimicrobial resistance as occurring “when microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites) change when they are exposed to antimicrobial drugs (such as antibiotics, antifungals and antivirals)”.

– Microorganisms that develop antimicrobial resistance are sometimes called “superbugs”. When antimicrobial drugs fail to kill these superbugs, infections may not be cured and can be spread more easily.

– While antimicrobial resistance occurs naturally over time through genetic changes in these organisms, the misuse and overuse of antimicrobial drugs – both in humans and farm animals – has caused the process to accelerate all around the world.

– The WHO estimates that 25,000 out of 400,000 peopleExternal link die in Europe each year due to infection with a resistant strain of bacteria.

– Currently, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are found in every country in the world. Resistant strains of K. pneumoniae, an intestinal bacterium, and E. coli are two of the most prevalent.

– The WHO offers a series of infographicsExternal link on how to avoid misusing antibiotics.

Voracious reader

Kathe says the inspiration for her project came from her fascination with nature, and her love of reading about science.

“I first read about these RNAs in Scientific American, and was immediately fascinated. I always find it interesting to read about new developments in physics, chemistry and biology,” she says.

“I’ve always been interested in nature and everything connected to it; maybe that is because of my parents and grandparents, who often went out with me into the forest to see what plants and animals we could find. The older I got, the more I wanted to understand the molecular mechanisms behind it – what makes a flower appear red, for example. That’s when I started studying math, physics, and chemistry in addition to biology.”

As a student at the University of Zurich Irchel campus, Kathe says she intends to continue studying these subjects, and hopes her experiment could form the foundation for a master’s or even PhD thesis. But in terms of career plans, she’s taking it one day at a time.

“It would be great if I ended up being a university professor or supervisor of a well-known laboratory, but for now I’m just focusing on completing my courses successfully. Every piece of information helps me understand the world better, or contributes somehow to my future projects.”

Nationwide campaign

Kathe’s award comes just in time for Switzerland’s inaugural National Antibiotic Awareness WeekExternal link, which will be held from November 13-19. The government-supported campaign will run for the first time in concurrence with the World Health Organization (WHO) International Antibiotic Awareness WeekExternal link, and aims to inform the public about the dangers of antibiotic resistance – for animals and the environment as well as humans – and provide the latest information on antibiotic usage best practices. Universities, consumer associations and other stakeholder groups will hold their own events across the country. A European Antibiotic Awareness DayExternal link is also planned for November 18.

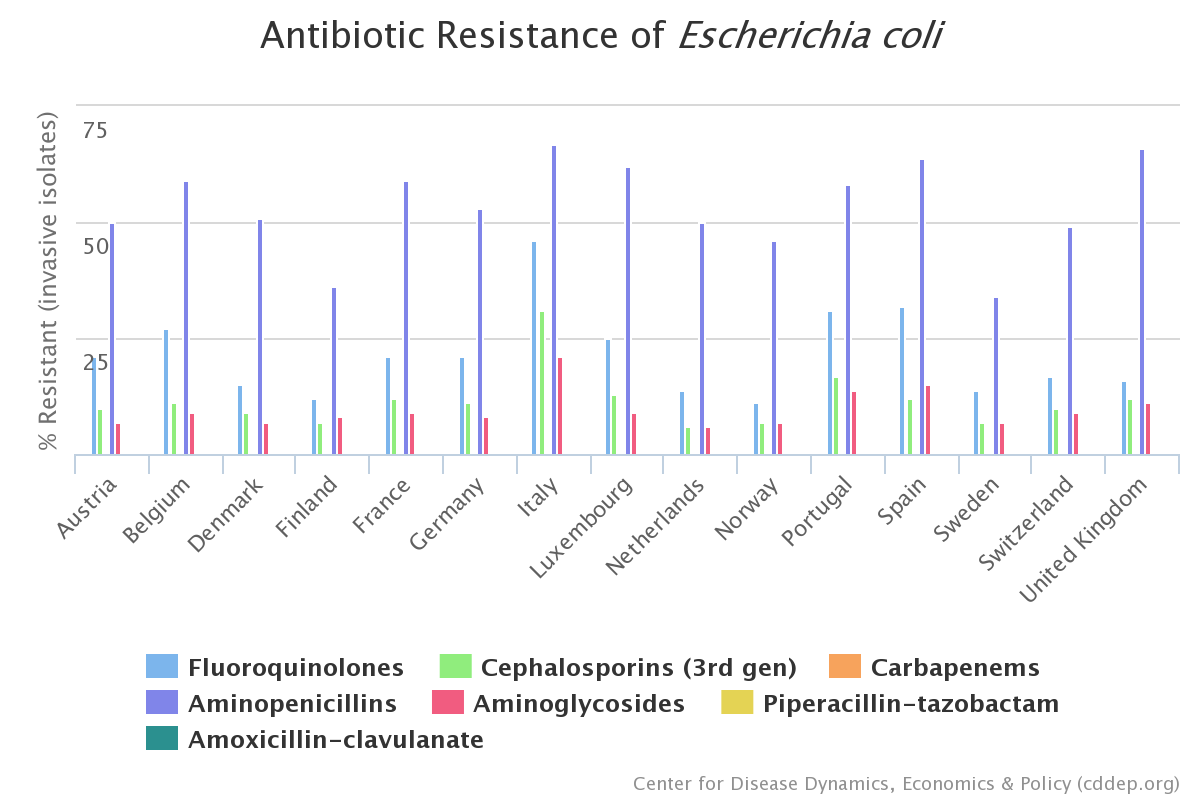

According to a 2015 report by the National Strategy against Antibiotic ResistanceExternal link (StAR), which organises the Antibiotic Awareness Week, Switzerland has managed to maintain overall lower levels of antibiotic resistance in human medicine than some other European countries – notably France, Italy and the United Kingdom – though not as low as those of Scandinavia and the Netherlands. Contributing factors may include Switzerland’s shift awayExternal link from the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and toward drugs that only target certain bacteria. In addition, back in 1999, Switzerland banned the addition of antibiotics to animal feed as growth promoters. Switzerland has also invested a great deal in monitoring national antibiotic usage and resistance levels, notably through the Swiss Centre for Antibiotic ResistanceExternal link; and in research, through the National Research Programme (NRP 72) on antimicrobial resistanceExternal link.

But even in Switzerland, resistance levels are on the riseExternal link in certain bacteria, especially E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus (“staph”). Kathe points out that changes in medical and agricultural practices are just as important scientific innovations when it comes to fighting this increase.

“People don’t have to be experts, but they should know that only bacterial infections can be treated with antibiotics, and that most infections of the upper respiratory system are viral infections, so it’s no use to ask the doctor for antibiotics. Doctors will prescribe these drugs if they are really necessary,” she says.

“I still have a lot of research to do, because my experiment was just the beginning. It’s not the solution to the problem [of antibiotic resistance] – just a way around it. We really have to change our behaviour to solve this problem and prevent it in the first place.”

Swiss survey: antibiotic use and attitudes

According to a 2016 Federal Office of Public Health surveyExternal link on antimicrobial resistance, 25% of Swiss residents took oral antibiotics in the past year, with the most having been taken by 15-24-year-olds in the nation’s French and Italian-speaking regions.

Most antibiotics were prescribed by a doctor or supplied by a hospital or pharmacist – very few were obtained outside of the Swiss health care system. About 75% of Swiss have a “good knowledge of antibiotics”, the study found, and the researchers concluded that it’s “widely known” among Swiss that using antibiotics when they are not strictly necessary results in them becoming ineffective. In a contradictory finding, although it’s generally understood that antibiotics can’t be used to fight against the common cold or flu, respondents appeared to be uncertain about the effect of antibiotics on viruses.

The data were based on a telephone survey of 1,000 respondents to better understand the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the Swiss population regarding antibiotic use.

More

Only use antibiotics if necessary, officials warn

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.