“Rolls-Royce” of x-ray machines honoured

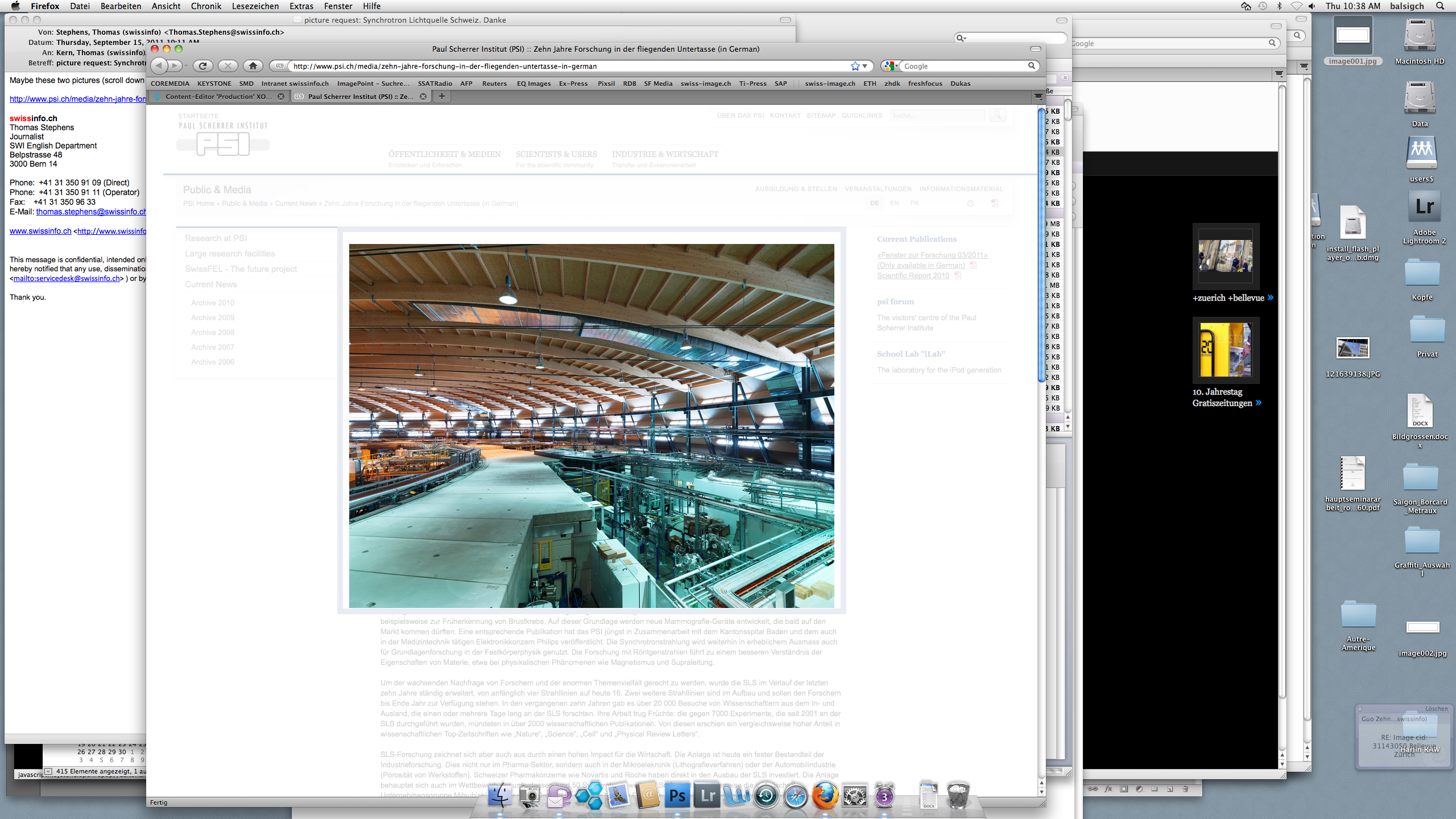

Is it a flying saucer? Is it a giant concrete doughnut? No, it’s a world-renowned particle accelerator and it’s just celebrated its tenth birthday.

The Swiss Light Source (SLS) is the sparkling jewel in the crown of the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI), Switzerland’s largest research institution – although the path to its creation couldn’t have been bumpier.

Since summer 2001, thousands of experiments have been carried out – by pharmaceutical researchers as well as academics – resulting in more than 2,000 scientific publications, one Nobel Prize and countless industrial applications.

This week, hundreds of physicists, former physicists, professors and Nobel Prize winners headed to the town of Villigen in northern Switzerland to pat each other on the back and discuss the machine’s birthing problems and subsequent acclaim.

Wander through Villigen and you can’t help noticing a lot of cows – and a 14,000 square metre concrete circle. This is the SLS, a so-called synchrotron in which electrons whizz around at near light speed and produce electromagnetic radiation – in other words, light – of blinding brightness.

“Landmark”

“Go into a room and turn on a ten-watt light bulb, then go again and turn on a 100-watt bulb and you already have to close your eyes. We increased it to a million-watt light bulb,” said Gerhard Materlik, a professor of physics and CEO of Oxford-based Diamond Light Source, the British national synchrotron science facility.

“If you want to look into the corners of nature, you simply see much more with this increased brilliance,” he told swissinfo.ch.

Materlik has worked closely with the SLS, which he describes as “very important, a landmark”, from the beginning.

“We can look into biological molecules – the ribosome [part of the cell that assembles amino acids to form proteins] has been a great breakthrough because it tells us how nature functions.”

Venki Ramakrishnan shared the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome”. A lot of his research was done at the SLS.

Pharma interest

The light produced ranges from infrared to hard x-rays, which can penetrate solid objects. The SLS specialises in the x-rays.

“We shine them through matter and take pictures on revolutionary scales of length and time – we can take pictures of objects that are as small as a few nanometres [billionths of a metre],” SLS director Friso van der Veen proudly told swissinfo.ch.

This was one reason, he added, why the pharmaceutical industry has a large interest in using the facility: to improve new medication by looking for example at the genetic structure of viruses.

“We can also look at the inner parts of fossils with unprecedented resolution without destroying them. This is important for understanding the full evolutionary tree,” he said (for other uses of synchrotron light, see link).

“Uphill battle”

But while the SLS now attracts the best brains in the world and has contributed to experiments published in prestigious journals such as Nature, Science and Cell, its construction was very nearly scuttled by political opposition.

Meinrad Eberle, director of the Paul Scherrer Institute from 1992 to 2002, told swissinfo.ch why the political challenges were greater than the technological ones.

“First of all it was a novel idea, so people didn’t know what we were doing. Second, the reputation of the Paul Scherrer Institute outside the [scientific] community was lousy,” he admitted.

“Now try persuading a politician to do something if you have a lousy reputation. It was extremely difficult. Ultimately it was a question of credibility. But I knew we had highly qualified people and this was the reason I stayed. We were successful, but it was an uphill battle.”

In his address, Eberle highlighted the contribution of Alex Müller, in the audience, who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1987. Basel-born Müller, now 84, was hailed as one of the first supporters of the SLS.

“Long fight”

Majed Chergui, head of the Laboratory of Ultrafast Spectroscopy at the Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), is one of the main external users of the SLS, with a third of his 17-person team based in Villigen.

“In my area, the SLS and the activities in the time-resolved x-ray domain are really at the forefront,” he told swissinfo.ch.

He acknowledged the “long fight” the SLS had to go through to get built, but said whenever you’re knocked down, you go away and think about it.

“In fact I’ve just been speaking to a guy who said it was a good thing they were rejected because they had to improve – they had to think about the scientific case and come up with something that was unrejectable,” he said.

“And that’s why this machine is a Rolls-Royce compared with other machines in the world.”

A synchrotron is a particular type of cyclic particle accelerator in which the magnetic field (which turns the particles so they circulate) and the electric field (used to accelerate the particles) are carefully synchronised with the travelling particle beam.

There are about 50 synchrotrons in the world.

The main component of the Swiss Light Source (SLS) is the 2.4 GeV (gigaelectronvolt – one billion electron volts) storage ring which has a circumference of 288 metres.

By comparison the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at Cern in Geneva has energy of 7,000 GeV and a circumference of more than 26km.

Planning on the SLS started in 1991, the project was approved in 1997 and first light from the storage ring was seen on December 15, 2000. The experimental programme started in June 2001 and is used for research in materials science, biology and chemistry.

The SLS cost SFr159 million ($182 million) to build and costs SFr13 million a year to run.

The Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities, and makes them available to the national and international research community.

Paul Scherrer (1890-1969) was born in St Gallen and later became head of the Department of Physics at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ).

His work led to the development of new branches of solid-state physics, particle physics and electronics, and this made a vital contribution to the high standard of research at Swiss universities.

The institute’s own key research priorities are in the investigation of matter and material, energy and the environment, and human health.

The PSI is Switzerland’s largest research institution, with 1,400 members of staff and an annual budget of roughly SFr300 million ($345 million).

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.