Swiss scientists discover 35 new bacteria in hospitals

Researchers in Basel in northwest Switzerland have found 35 new species of bacteria in patient samples taken at hospitals. Seven of them can cause infections in humans, a study published on Monday shows.

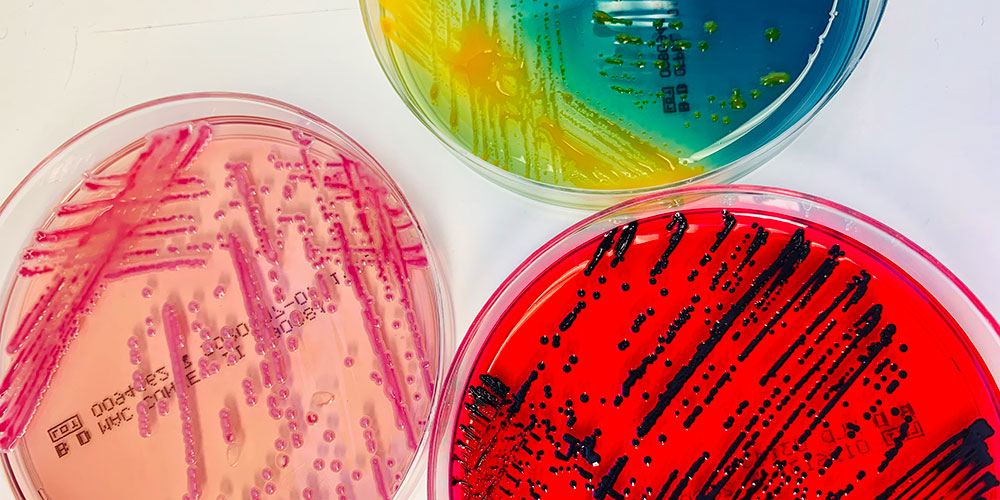

A team from the University of Basel and the University Hospital of Basel has been collecting bacteria samples from patients with a wide variety of illnesses since 2014.

Overall, the team led by the microbiologist Dr. Daniel Goldenberger analysed 61 unknown bacterial pathogens found in blood or tissue samples from patients with a wide range of medical conditions.

+ Swiss government wants to tackle antibiotic resistance

Conventional laboratory methods, such as mass spectroscopy or sequencing a small part of the bacterial genome, had failed to produce results.

That is why the researchers sequenced the complete genetic material of the bacteria using a method that has only been available for a few years. They then compared the identified genome sequences with known strains in an online tool.

+ A weapon against superbugs lies in the Rhine River

Of the 61 analysed bacteria, 35 were previously unknown, the university said on Monday in a press release.

Anyone who discovers a new species can choose its name. So far, the Basel researchers have named two of the bacteria, according to the university. One is named Pseudoclavibacter triregionum, based on Basel’s location on the border between Switzerland, France and Germany.

+ Swiss fight drug-resistant bacteria on many fronts

According to the researchers’ analysis, seven of the largely unnamed bacterial species are clinically important, i.e. capable of causing infections in humans.

Many of these types of bacteria would be found naturally in the skin and mucous membranes. “For this reason, they are often underestimated and have received little research,” study leader Daniel Goldenberger said. However, if they enter the bloodstream, for example due to a tumor, they could trigger infections.

This news story has been written and carefully fact-checked by an external editorial team. At SWI swissinfo.ch we select the most relevant news for an international audience and use automatic translation tools such as DeepL to translate it into English. Providing you with automatically translated news gives us the time to write more in-depth articles. You can find them here.

If you want to know more about how we work, have a look here, and if you have feedback on this news story please write to english@swissinfo.ch.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.