‘Empress stabbed in the heart’

In 1898, the Empress Elisabeth of Austria was murdered in Geneva. The popular "Sisi" was stabbed to death by an Italian anarchist. It was a sensational case that aroused strong feelings around the world, including anger against Switzerland. Yet the country held fast to its open borders.

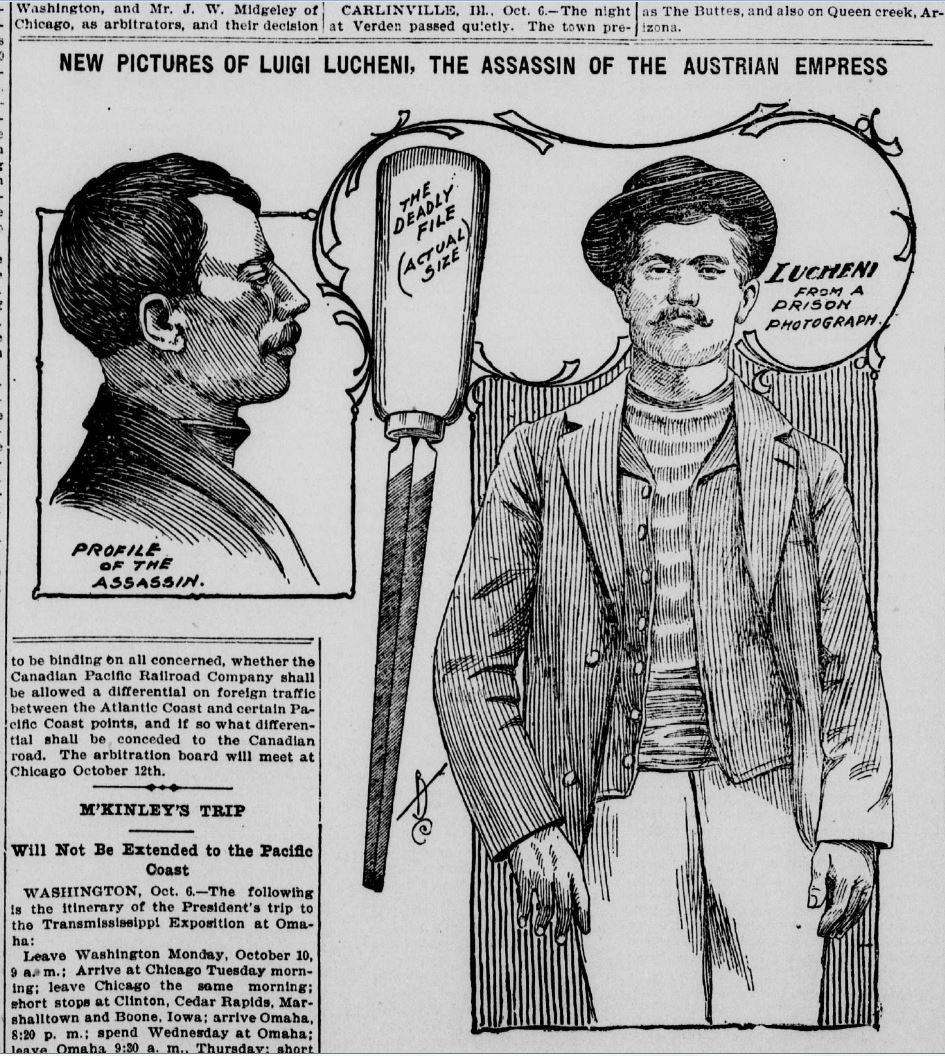

With a blow of its whistle, the steamer “Genève” announced its immediate departure. Empress Elisabeth and one of her ladies-in-waiting had just reached the gangway to board, when an unknown man lunged forward and stabbed the Empress in the heart with a sharp weapon.

Without a sound she fell to the ground. Passers-by helped her up, and the lady-in-waiting – according to legend – anxiously asked: “Your Majesty, shouldn’t we go back to the hotel?” Elisabeth replied: “Oh no, it’s nothing! He just knocked against me, he must have been after my watch.”

Smiling to jail

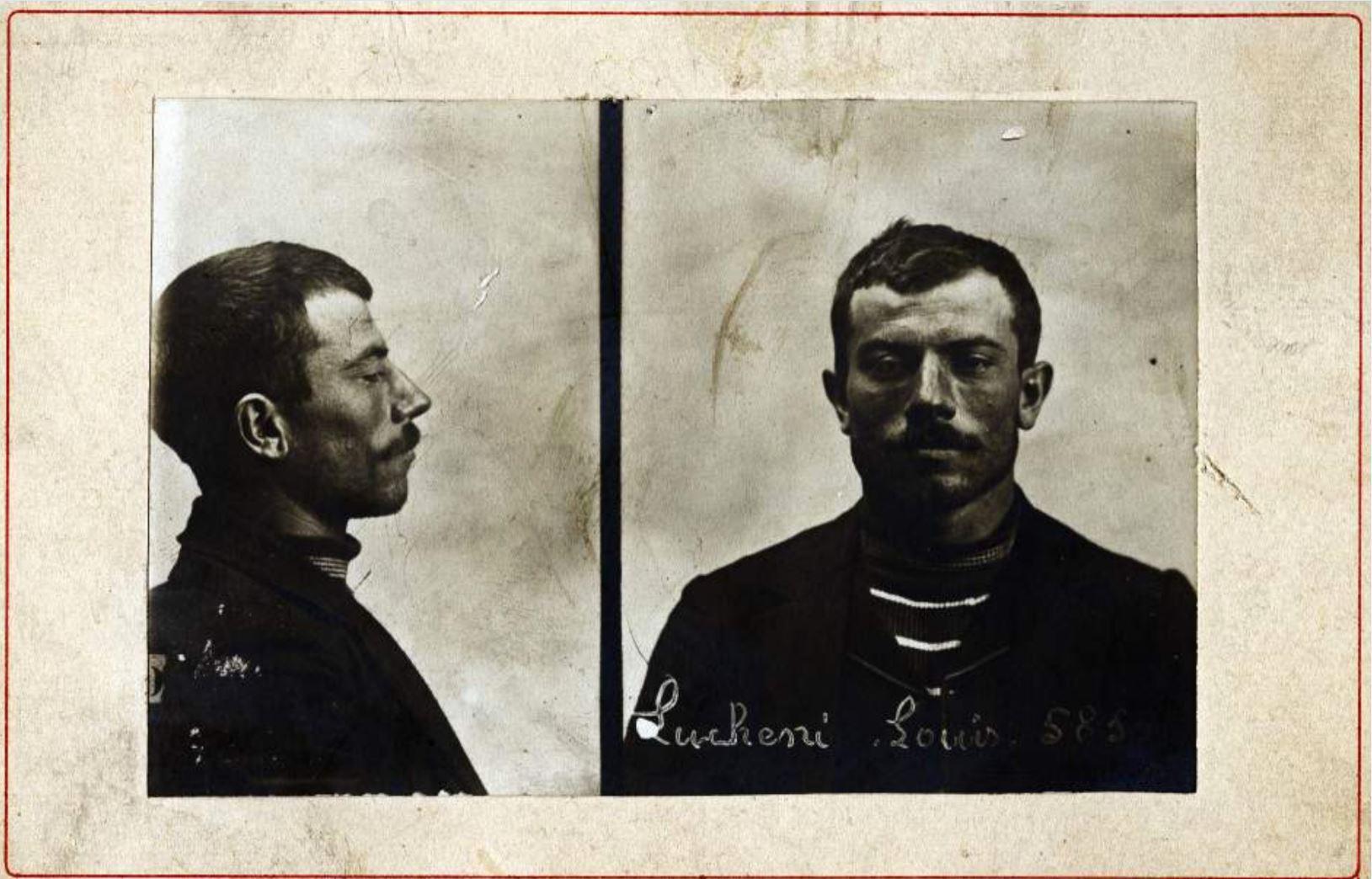

Two coachmen ran after the suspected thief, who was making good his escape. When they captured him and handed him over to police, he told all. “I got her”, he declared, “She must be dead.” Down at the station he told the desk-sergeant that he was an anarchist, and if all anarchists had his sense of duty, there would soon be no bourgeois society or injustice left.

While Luigi Lucheni was being questioned, doctors were fighting to save the life of the Austrian Empress. Shortly after the attack, she had fainted. She was brought back to her room in the Hotel Beaurivage where she died soon after. It was September 10, 1898.

The news shocked the world. It was not the first such attack on one of the crowned heads of Europe. The kings of Spain and Italy and Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany had been wounded in attacks by anarchists, and Czar Alexander II of Russia had been killed (see part 1 of this series). The anarchists also targeted politicians, judges and prosecutors.

Three years previously, the president of France had been stabbed, and the Italian and Spanish prime ministers had had narrow escapes. But there had not yet been an attack on a female monarch.

Consternation across the Atlantic

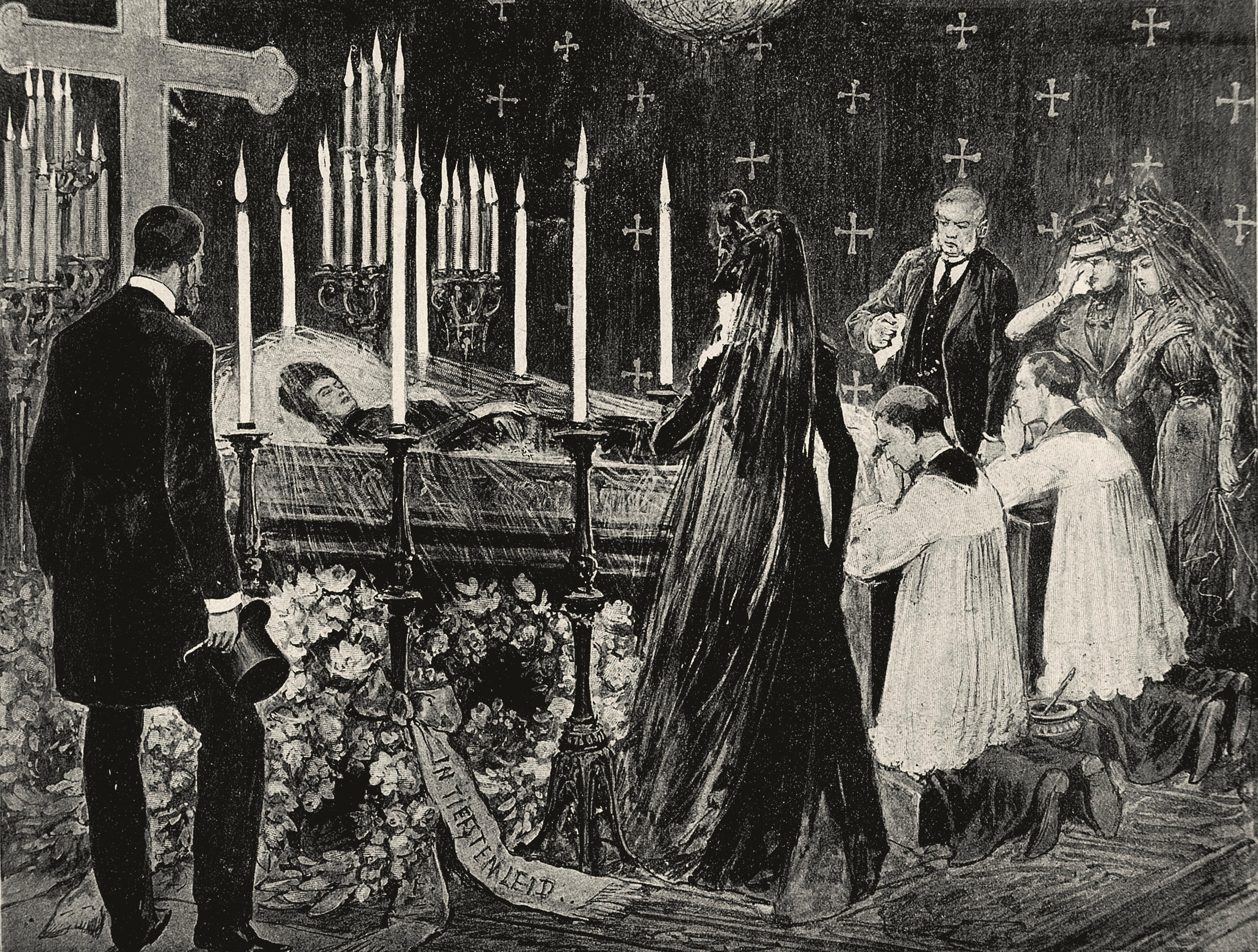

Europe was shaken. In Vienna, as the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung reported, people were “horrified, stunned, grief-stricken and indignant about this monstrous deed.” One Viennese lady was heard demanding loudly that the offender should be “cut up in little pieces”. In Budapest, men as well as women wept openly in the streets. In Paris, the news “had come like a bolt from the blue”, the Petit Journal wrote. Newspaper vendors were “besieged by crowds”, and publishers distributed extra editions for free.

American popular newspapers printed portraits of Sisi and ran headlines such as: “ELISABETH OF AUSTRIA ASSASSINATED BY AN ANARCHIST. EMPRESS STABBED IN THE HEART. The dreadful deed was committed by an Italian in Geneva.”

In Switzerland too, which had seemingly been miraculously preserved from anarchist attacks, people mourned for Sisi. In Geneva, the consternation was particularly keenly felt. Flags flew at half-mast; shops closed; theatres cancelled performances; politicians and diplomats trooped to the Hotel Beau-Rivage to pay their respects to the dead Empress.

Mark Twain, who was in Europe at the time, wrote to a friend: “even the assassination of Caesar himself could not electrify the world as this murder has electrified it.” The next day, which was a Sunday, crowds queued to sign the condolence book that had been opened at the Hotel Beau-Rivage.

Political crisis

There was an emergency sitting of the Federal Council in Bern, and regret was expressed that the Empress had travelled to Geneva incognito and had declined a police escort. Nonetheless, Switzerland found itself accused by the press in neighbouring countries of “giving safe haven to extremists of all sorts” and because of its liberal asylum policy “taking in whoever comes, including criminals from every country under heaven.”

“Even the assassination of Caesar himself could not electrify the world as this murder has electrified it.” – Mark Twain

In Switzerland there began to be demands for all anarchists to be expelled. When “noble women”, as the Neue Zürcher Zeitung complained, were not longer safe from “the daggers of dehumanised fanatics”, all methods were good that would free society “from the plague of anarchism”.

The conservative press took the opportunity for an all-out attack on Socialists, accusing them of excessive tolerance of anarchist violence.

The Socialists were quick to defend themselves. They condemned the “ruthless attack” on a defenceless woman, and pointed out: “It is our aim to kill capitalism. This can be done without killing a single human being.” Lucheni, who had been an illegitimate child, grew up in an orphanage, and was sent to work as a child labourer on a farm, was, from the Socialists’ point of view, a victim of an unjust system.

“Capitalist society is what gives rise to these anarchists, and it has no right to complain now about what it has produced”, a Socialist speaker told a meeting. “It put the weapon in the hand of this killer too.”

Liberal asylum law prevails

Despite ideological differences, people in Switzerland were in broad agreement that it would do no good to restrict the law of asylum, and certainly not in response to political pressure from other countries. Socialists were adamant that “more police presence, more restrictive surveillance of foreigners, or a ban on guns would not help to get rid of these anarchists.”

The conservative Neue Zürcher Zeitung argued from a similar liberal viewpoint. It said the “notion of freedom in Europe” would be seriously threatened if Switzerland gave up its “proud position” as country of safe haven. Repression was no guarantee against political violence: “Desperate people can be hunted from one country to the next, but at some point they will get their chance, and they will use it to their best advantage. It may be humbling for us to admit that with all our advanced civilisation we cannot be entirely secure, but it is so, and it would be well for us to recognise it.”

In the meantime, the investigation of the crime was proceeding quickly. Lucheni had said he acted alone, but the investigators thought there might be an anarchist conspiracy. People were questioned in Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Naples, Parma, Lausanne and Zurich. A number of anarchists were arrested, but had to be released for lack of evidence.

Trial makes world news

On November 10, 1898, two months after the assassination, Lucheni finally appeared in court. Sixty reporters from around Europe, four of them women, applied for accreditation. The public prosecutor read out a report from the famous psychiatrist Cesare Lombroso, who had developed the now-discredited theory of the criminal personality. Lombroso found the explanation for this crime in the fact that Lucheni had been the son of a “choleric drunkard” and had thus inherited the tendency to criminal behaviour.

‘I must have gone to school no more than two or three times.’ Luigi Lucheni

Lucheni himself told judge and jury that he had wanted to exact revenge for his wretched life: “My mother denied me and abandoned me as soon as I was born. (…) And think of the family I grew up in. They had not enough to feed their own child. I must have gone to school no more than two or three times.”

Someone who had lived with Lucheni reported that he had told him: “I would like to kill someone, but it would have to be some well-known person, so that it was all over the papers!”

Since Lucheni expressed no remorse, the one-day trial ended in him receiving a life sentence. As he was taken out of the court, he shouted: “Long live anarchy! Down with the aristocrats!” – though if the reporting journalists are to be believed, there was more fear than triumph in his voice.

Two weeks later, in Rome, representatives of 21 countries took part in the first International Conference for the Defence of Society against Anarchists. They agreed to take stronger measures against anarchists, to restrict reporting of anarchist activities and to require the death penalty for assassins of heads of state.

They also agreed on a uniform system to track suspects, and further international exchange of information between police forces.

Memoir disappears

Luigi Lucheni spent the first two years of his sentence in a solitary cell, where he was put to work making slippers. When his prison conditions were relaxed due to good behaviour, he wrote a memoir of his childhood, a shattering testimony to the life of the poor in Europe in the late 19th century.

In the spring of 1909, however, the two-hundred-page manuscript disappeared from his cell “in mysterious circumstances”. Lucheni was furious and complained to the prison governor. The situation only got worse. Lucheni had outbursts of uncontrollable anger and wrecked his cell, whereupon the governor invoked disciplinary measures. He had a picture of the Empress Elisabeth removed from Lucheni’s cell.

On October 19, 1910, Luigi Lucheni hanged himself with his own belt in his cell. But even death failed bring peace to him. The same professor of medicine who had carried out the autopsy on Empress Sisi decided to study Lucheni’s brain to see if there was anything in the internal structure that might point to inherited criminal tendencies. He found nothing. But afterwards, he kept the severed head of Lucheni in a jar of formaline.

The grisly trophy remained in the collection of the Forensic Medicine Institute of Geneva University until 1985, when it was sent to Vienna. But it was only in the year 2000 that Lucheni’s head was secretly buried in the main cemetery in Vienna – only a few miles from the royal crypt where the Empress Elisabeth, his victim, had found her last resting-place.

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.