Value added tax: the Swiss government’s all-purpose tool

Switzerland has the lowest VAT rate in Europe. Now the Swiss government wants to increase it from 8.1% to 8.9% to pay for national defence. An explainer on the Swiss peculiarities of the most commonplace of all taxes.

Why does the Swiss government want to increase VAT?

The Swiss government wants to increase VAT by 0.8 percentage points for ten years from 2028 in order to strengthen defence.

Switzerland has placed less importance on its defence capabilities in recent decades. Now the defence ministry has come to the conclusion that the threat situation for Switzerland will be particularly great in the coming years, with Russia ready for a major attack on Europe via Ukraine as early as 2028. “Switzerland is also affected by these developments and is already confronted with hybrid conflict management,” the governing Federal Council states.

The threat also results from a weakening of NATO. Surrounded by NATO countries, Switzerland has benefited from their security architecture in recent decades. Now it must take significantly more responsibility for its own defence. According to the Federal Council, the measure is being taken “to protect the population and the country and to avoid posing a security risk in Europe’s defence architecture in the future”.

What is value added tax?

Switzerland introduced value added tax in 1995. It started at a rate of 6.5% and replaced the former goods turnover tax, which was only levied on sales goods and not on services. Three previous attempts to introduce VAT had failed at the ballot box.

VAT in Switzerland is a consumption tax and is standardised throughout Switzerland. It is levied directly on consumers – not only on goods and services, but also on imports. This is why the VAT rate is sometimes mistakenly understood as the Swiss customs tariff.

Companies that levy this tax deliver their revenue to the federal government. It is therefore an important source of revenue for the federal government. It currently contributes CHF28 billion to the federal budget of CHF90 billion.

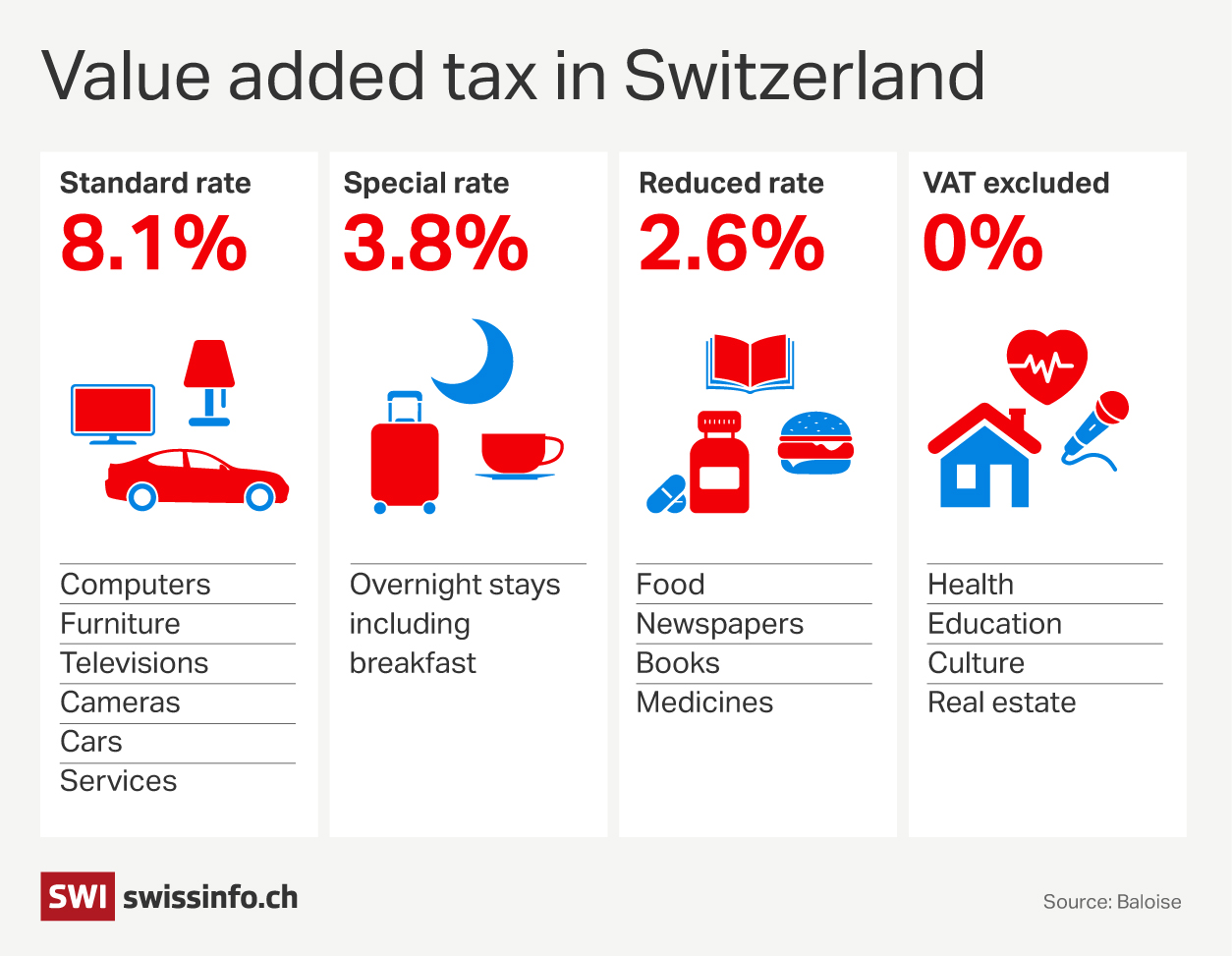

What VAT rates apply in Switzerland?

The standard rate is 8.1% and covers consumer goods. A special rate of 3.8 applies to the hotel industry. A reduced rate of 2.6% applies to numerous everyday goods, including food and medicines. Health services, education and culture are completely exempt from VAT.

Why is Swiss VAT relatively low?

The member states of the EU have significantly higher VAT rates. One reason for this is that the EU stipulates a minimum tax rate of 15%. The average rate for EU countries is around 22%. Luxembourg has the lowest rate in the EU (16%), followed by Malta (18%), Cyprus and Germany (19%). Croatia and the Scandinavian countries charge the highest rates in Europe at 25%. The front-runner is Hungary with 27% VAT.

“One factor behind the low Swiss rate is Switzerland’s fiscal restraint, which manifests itself in the Swiss debt brake,” says Michele Salvi, Deputy Director of the liberal economic think tank Avenir Suisse. This debt brake forces Switzerland not to spend more than it earns.

Can the Swiss government unilaterally decide to increase VAT?

No. “Another factor in the low Swiss rate is direct democracy,” explains Michele Salvi. “Every tax increase must be approved by the people as a constitutional amendment.” This prevents the government from simply raising taxes for debt restructuring or short-term investments.

Parliament must first decide on this. This is where things get difficult in the current case. The left-wing Social Democratic Party will not support a special defence budget that includes the controversial US F-35 fighter jet as a major budget item. On the other hand, the powerful right-wing Swiss People’s Party will not be prepared to increase taxes. Instead, it sees opportunities for savings in the areas of asylum, bureaucracy and development aid.

What does Switzerland need VAT for?

VAT is just one of several taxes levied in Switzerland. Residents pay their income and wealth taxes to their municipalities and cantons of residence.

However, this does not cover the expenses of the federal government. A third is spent on welfare while transport, education and security together account for a further third.

Since its introduction in 1995, increases in VAT in Switzerland have usually snuck in as a temporary, earmarked special tax – or to plug holes in the social security system.

The first increase took place in 1999 with the aim of financing old-age and disability insurance. In 2001, the rate rose again slightly in order to build the new transalpine railway link – a CHF 24 billion project. In 2011, the rate was increased for a limited period of seven years in order to plug a billion franc gap in disability insurance.

Can VAT also finance pensions?

This is highly controversial politically. The Federal Council wanted to increase VAT as early as 2026. However, parliament has stopped the plan. VAT could actually help to finance pensions. Specifically, the 13th monthly pension for all pensioners that the majority of Swiss voted for in 2024. This could raise an additional CHF4.2 billion per year.

However, old-age pensions are based on a structural deficit. The population is getting older. Many members of the baby boomer generation are now retiring which increases pension costs. At the same time, fewer younger people are paying in. This is why many politicians are in favour of other solutions. From the right to the centre, the recipe is austerity measures and an increase in the retirement age. Those on the left are fighting for an adjustment to the debt brake.

Is value added tax unfair?

Economists are arguing about this. At first glance, there does not appear to be any social justice in the sense that poorer people benefit and the rich shoulder the cost. After all, the same rate applies to all consumers and there is no progression.

“VAT is not a flat rate tax on consumer spending,” says economist Isabel Martinéz from ETH Zurich. Analyses of household budgets have shown that almost all consumption by low-income households is spent on goods and services that have low or no VAT rates. This is the case for rent, insurance and food, for example. “Households with the highest incomes, on the other hand, pay full VAT on around 70% of their expenditure,” writes the economist.

It is therefore a question of observation: if the assessment basis is income, then VAT is not progressive. However, if consumption is assessed, there is at least a tendency towards social equity. The former Swiss price watchdog Rudolf Strahm – a Social Democrat – also argues in this way: “The effective VAT burden on household expenditure is not linear, but slightly progressive towards the top”.

However, other experts see an injustice in the fact that the powerful Swiss financial sector is largely exempt from VAT. If exempting insurance companies actually relieves the burden on many consumers, exempting banks can be seen as a gift to banks and the wealthy.

Edited by Samuel Jaberg. Adapted from German using AI/ac

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.