The fictional freedom fighter

William Tell stands alongside George Washington, Joan of Arc and Robert the Bruce as one of the western world’s best-known champions of freedom and independence.

But there is no evidence that there ever was a William Tell, which begs the question: why have the Swiss elevated a fictional figure to the status of national hero?

The Swiss have had their share of flesh and blood heroes. There were the confederation’s founding fathers; Werner Stauffacher, Arnold von Melchtal and Walter Fürst. But few Swiss can remember one let alone the names of all three.

And a large cast of dukes, theologians and military commanders have carried out heroic acts through the ages, and have been immortalised in statues and street names across the country.

But not one, now matter how real or great the deeds, comes close to Tell who embodies the qualities the Swiss hold dearest.

“Tell is the best symbol whenever people dream of freedom and independence,” says Sergius Golowin, Swiss author of several works on myths and legends.

Eternal image

“It’s an eternal image,” Golowin explains. “The story is also told of how, as an old man, Tell dies saving a baby from a torrent. His whole life was a symbol for freedom and unselfish acts to guarantee the rights of others.”

And desire for liberty, Golowin continues, was the single unifying force that bound a people who thought they had little else in common.

“The people of the three founding cantons did not think they were of the same race,” Golowin says, “despite the fact that Schiller wrote ‘we are all one heart, one blood…one people’.

“The people of Uri thought their forefathers migrated to the region from the east, while those of Schwyz were convinced they stemmed from Nordic tribes.

“Their compatriots in Unterwalden considered themselves direct descendants of the Romans or Greeks,” Golowin says.

Schiller’s contribution

The crossbow-toting marksman was already 500 years old when Schiller breathed new life into him, turning the Swiss figure into a universal symbol of freedom.

Tell was reborn again in the Second World War, according to Pierre du Bois, professor at Geneva’s Graduate Institute for International Studies.

“A group of intellectuals relaunched the myth to reinforce the national identity when Switzerland was surrounded by the countries of the Third Reich,” du Bois says.

And a statue of Tell in the House of Representatives reminds parliamentarians of Switzerland’s special status in the modern era, surrounded as it is by European Union countries.

Yet du Bois says parties and groups opposed to EU membership would be wrong to use the symbolic figure to fight closer ties.

“I think Tell as a symbol is in decline,” he says. “There has been a change in our customs and mentality and I don’t think he’s a vital figure anymore, at least not for the younger generation.”

But Golowin thinks the legend will live on. “There are places in the world today where people have never heard of Switzerland, but they know the story of William Tell.”

swissinfo, Dale Bechtel

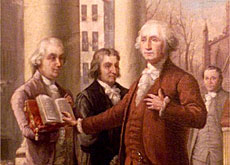

The United States has countless flesh and blood heroes led by George Washington.

Britain, Spain and France celebrate numerous kings, queens as well as swashbuckling adventurers and explorers.

Scotland has Robert the Bruce and William Wallace.

Among Tell’s fictional brethern are King Arthur, Robin Hood and Spain’s El Cid.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.