Nanny trafficking for the middle class

Young Albanian women come to Switzerland because they want to look after babies – a nice job in a safe country. But many end up in the clutches of human traffickers. Part 2.

Investigation and text: Adelina Gashi, Marguerite Meyer. Investigative collaborator: Vladimir Karaj.

What happened so far (Part 1): There is a system that lures Albanian women to Switzerland as nannies. And they end up in the hands of human traffickers. Shpresa is one such woman.

In a local courtroom, an appeals hearing is taking place. Apart from us, only the defendants (spouses), the district judge, his assistant and another journalist are present. An unspectacular scene, at first glance.

The couple had been convicted at the first instance of employing foreigners without a licence. Now they are appealing the ruling. Both are in their forties and seem distraught and desperate, without a lawyer or public defender. She is a shop assistant on call, he commutes as a mechanic fitter. For them and their four children, their household income totals around CHF6,500 a month.

The UN defines Human TraffickingExternal link as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of people through force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them for profit. Men, women, and children of all ages and from all backgrounds can become victims of this crime, which occurs in every region of the world. The traffickers often use violence or fraudulent employment agencies and fake promises of education and job opportunities to trick and coerce their victims”.

The vast majority of perpetrators are menExternal link. Women who become co-perpetrators have usually been previously exploited themselves.

The young woman, Shpresa, is not present in court. Where is she? “We don’t know,” the couple says. She had been picked up by a taxi. The husband says he doesn’t know who the people in the car were. We will stumble upon this very taxi company again in a conversation with a different victim.

Shpresa did not leave Switzerland that day. She was arrested as an “overstayer” a month later during a police identity check. She told the police that she had to work for the couple as a nanny and housekeeper – for half as much money as promised. Someone had forged her passport; she did not know who.

The public prosecutor’s office began to investigate. Shpresa, however, was deported and banned from entering Switzerland for two years. She wasn’t brought in for questioning at the trial, and the Albanian authorities weren’t asked for assistance. The court ruled that Shpresa’s statements to the police could not be used as evidence.

A commodity and its supply chains

This example seems to reveal the general helplessness of the Swiss authorities and the lack of coordination in the fight against human trafficking. It’s as though the court wants to get it over and done with fast: victim no longer traceable – acquittal for the couple. The perpetrators: undisturbed.

“We stopped looking at human trafficking as a stand-alone industry a long time ago,” says Stephan Fuchs from Trafficking.ch. “People who recruit nannies this way are most certainly involved in other business, such as drug dealing.”

We want to track down Shpresa. So we travelled to Albania one more time. Together with our local investigative colleague, we carefully feel our way around, looking for clues in her small hometown. But we cannot work out how Shpresa came to Switzerland. Or what happened to her afterwards.

Contrary to the cliché, trafficked people are rarely transported in darkened trucks. In most cases, they travel along ordinary routes – by bus, plane, taxi or car. In this industry, humans are a commodity like any other. A commodity with which money can be made. The supply chains are international.

Human trafficking and people smuggling are not the same thing. Smugglers bring people from A to B, the profits are generated by providing the transport service. In human trafficking, transport is only the means to an end – the core of the business is the exploitation of labour or the body. However, the two forms are often intertwined.

The traffickers have their accomplices along their route. Sometimes it is a bus driver who just collects the money for the ticket upon arrival in Switzerland. A border guard who does not check a passport too closely. Or a taxi company that is grateful for its regular customers and prefers not to ask questions about the ever-changing women in its cars.

In Lirije’s case, it was the driver of the coach that took her from Albania to Switzerland. “He was on the phone during the ride,” she remembers. Then, he gave an affirmative nod before handing her a few hundred euros. Sometimes people are checked at national borders to make sure they have enough cash on them for their stay. “After the Swiss border, he took the money from me again,” Lirije says.

And then she was dropped off at a bus station. Her employer picked her up. They had already discussed everything over the phone; he knew of her difficult circumstances back home. He paid for the bus ticket and drove Lirije to the outskirts of a Swiss city.

It is a modest neighbourhood, with housing blocks scattered randomly across what was once a field. There are prams in the entrances to the buildings and notices from management on the wall informing residents what is prohibited. People with tired faces wait for the bus.

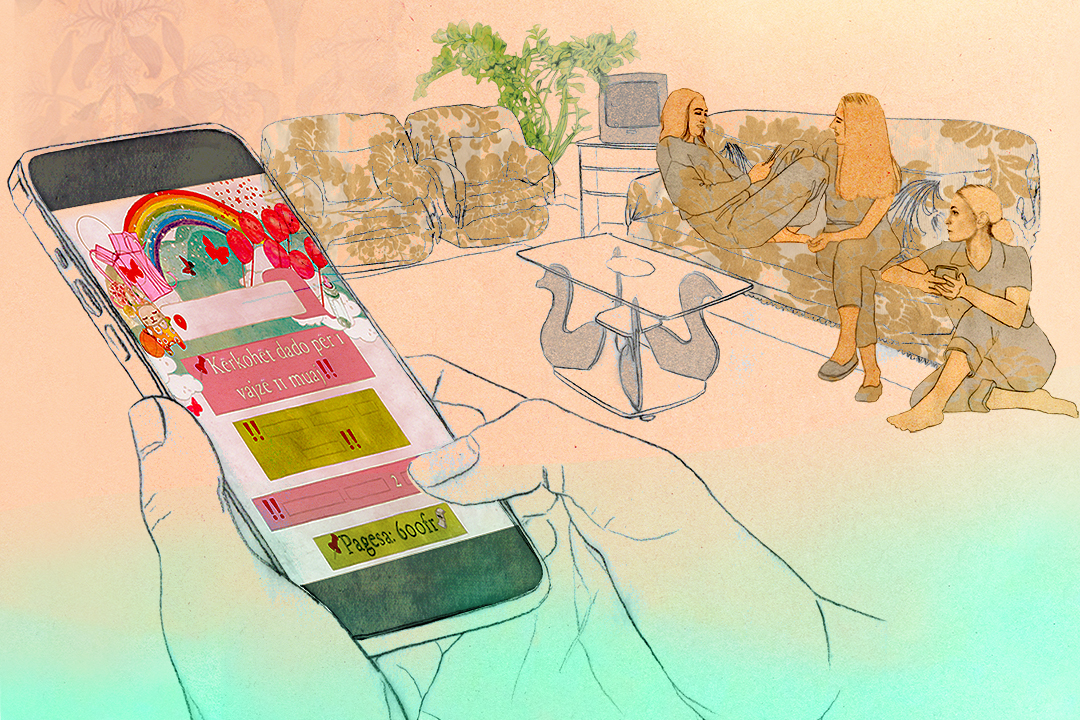

It is here that the Swiss lower middle class and the modern precariatExternal link live, as well as the country’s cleaners, carers, plumbers, shop assistants and construction workers. It is these people and their families who typically look for such nannies because they need support in their everyday lives – which they cannot really afford. Here, in this faceless agglomeration, Lirije does not begin her hopeful new life. Instead, it is a journey through hell.

A web of dependencies

From the outside, human trafficking is difficult to recognise. It involves not only forced prostitution but also the exploitation of ordinary labour. It can affect the waitress at your favourite café or the worker on the building site next door.

“In Switzerland, we lack a comprehensive understanding of what human trafficking really is,” Fuchs says. The cantons are responsible for its criminal prosecution. There are huge differences between them, according to a report commissioned by the Federal Office of Police (Fedpol). “There are dozens of working groups in the cantons, but something like this actually has to be investigated at the Europol level in each individual case,” Fuchs says.

The problem is underestimated or there is a lack of funds. Furthermore, outdated perceptions associate human trafficking primarily with the sex trade, according to the study. Often, too little attention is paid to labour exploitation.

Initially, a relationship of dependency is usually created through deception, debt and the exploitation of family circumstances. Once the victims are in Switzerland, the net closes tightly. Victims do not know the country, cannot speak the language and have no contacts other than the perpetrators. Albanian, North Macedonian and Kosovar nationals can stay in Switzerland legally for three months without a visa. However, they are not allowed to work during this time, unlike citizens from the EU or EFTA countries.

In Albania, some things are no different from in Switzerland. “Young people often don’t think of health insurance and old-age pension as a priority,” says Iris Luarasi, the Albanian women’s rights expert. “They think they can take care of documents once they have arrived.”

By working illegally, however, they become offenders from the very beginningExternal link. This is shamelessly exploited by the perpetrators. It is a perfidious scam that the Federal Office of Police also recognises as suchExternal link: the victims have no choice but to allow themselves to be exploited.

In the course of our investigation, we read through court files that tell of psychological and physical cruelty. Of emotional blackmail and sexual assaults. Women report beatings, humiliation and death threats, also towards their families. We listen to voice messages from perpetrators filled with violent insults.

Sometimes the future victims know they are getting involved in illegal labour in Switzerland. Or they are deceived like Ardita was.

How was Ardita’s trust in the Swiss legal system exploited? And why does she receive vicious abuse via voice message? Find out in part 3.

This investigation first appeared in the Swiss magazine “Beobachter”. It was made possible with the support of JournaFONDS and the Real 21 media fund.

An Albanian version is available on the investigative platform “Reporter.al”External link.

The German version is available on “Beobachter.chExternal link”.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.