A journey through the hundred valleys

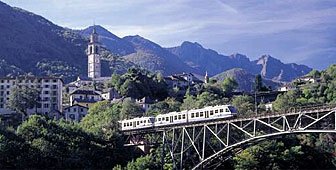

There are easier ways of getting from Italy to Switzerland, but few are as spectacular as the train journey through the valley of the "hundred valleys". Dale Bechtel took the 55-kilometre trip between the Italian city of Domodossola and Switzerland's Locarno, which crosses 83 bridges and passes through more than 30 tunnels.

The narrow gauge electric train, run jointly by Italy’s SSIF Railway and Switzerland’s Centovalli (hundred valleys) Railway, winds its way slowly up the mountainside from Domodossola. Every twist gently jerks the passengers from side to side but rewards them each time with a new view of the terracotta buildings of the city below.

The first stop after tackling the steepest part of the climb is Trontano, a village surrounded by small vineyards. The gnarled vine stocks are bound to bent wooden posts and beams, as was the practice when the monastery held sway in Trontano.

Little has changed in Trontano – from the train window at least – or many of the other villages in Italy’s Vigezzina valley and Switzerland’s valley of the “hundred valleys” since the building of the railway nearly 80 years ago.

Prosperity to valleys

“When the idea developed to build a railway, the aim was to bring a little bit of prosperity to the valleys,” says Dirk Meyer, director of the Centovalli Railway. “But when the railway opened in 1923, this did not happen.”

Instead, the line has developed into one of Switzerland’s classic railway journeys through the Alps. Insiders know it as the most scenic way of getting from canton Bern or western Switzerland to the sunny southern canton of Ticino.

Hikers cherish the access it provides to the large network of trails through the wild and unspoilt “hundred valleys” and culture seekers hop on and off the train to discover the many medieval villages and hamlets clinging to the steep slopes.

The train reaches the railway’s highest point when it stops at Santa Maria Maggiore at 816 metres above sea level. It then passes through high stands of pine trees before beginning the slow descent towards the Swiss border.

After the village of Rè, dominated by a grandiose church – an odd mix of Gothic arches and Byzantine domes – the valley narrows abruptly and the tracks skirt along a gorge.

The train has reached the entrance to the Centovalli.

At Camedo, a simple greeting is all that marks the handover between the Italian and Swiss crews. It’s the sign of an enduring partnership between the two railways which goes back to the early 20th century.

Political obstacles

At that time, one Swiss man and his Italian partner not only had to achieve an engineering feat to build the line through an inhospitable landscape, but had to deal with political obstacles as well.

“I think these people had a vision and were really pioneers who weren’t worried about borders,” says Meyer.

Despite the persistence of these two pioneers, the government in Rome blocked the project for years fearing its construction would expose Italy to attack in a time of hostilities. The start of the First World War put the project on hold indefinitely.

Once building finally began, the only way for the engineers to overcome the difficult terrain was by building a succession of bridges and tunnels, particularly on the Centovalli side.

After leaving Camedo, the gorge seems to swallow up the tracks. At one point, the train travels close to the bottom before entering a tunnel. When it emerges a few seconds later, passengers are surprised to find that they are suddenly a couple of hundred metres above the ravine.

At Verdasio, a few passengers get out and take the cable car that spans the gorge on its way up to the village of Rasa. The only other way to get to the village is on foot. Many of Rasa’s original stone houses have been carefully restored as holiday homes, and are occupied mainly during the summer months.

Two climate zones

The train crosses a high steel bridge after Intragna, marking the end of the Centovalli. The crossing also bridges the gap between two very different climate zones, with the landscape suddenly taking on a bright Mediterranean air.

Passing palm trees set in lush gardens, the descent to Locarno and Lake Maggiore begins.

The last stop before Locarno is Ponte Brolla. Outside its depot is the train that took part in the inaugural run of the railway in 1923. It has since been put back into service during the busy summer season, and its interior, with first, second and third class seating, has been faithfully restored.

Nearing Locarno, the train enters the final tunnel, which takes it below the small city. The modern Locarno station for the Centovalli Railway is the end of the line and located directly beneath the city’s main railway station.

For visitors arriving in Locarno from other points of the compass, the secret to a spectacular journey through Switzerland’s valley of the “hundred valleys” lies under their feet.

by Dale Bechtel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.