Switzerland is still grappling with dark chapters of its history

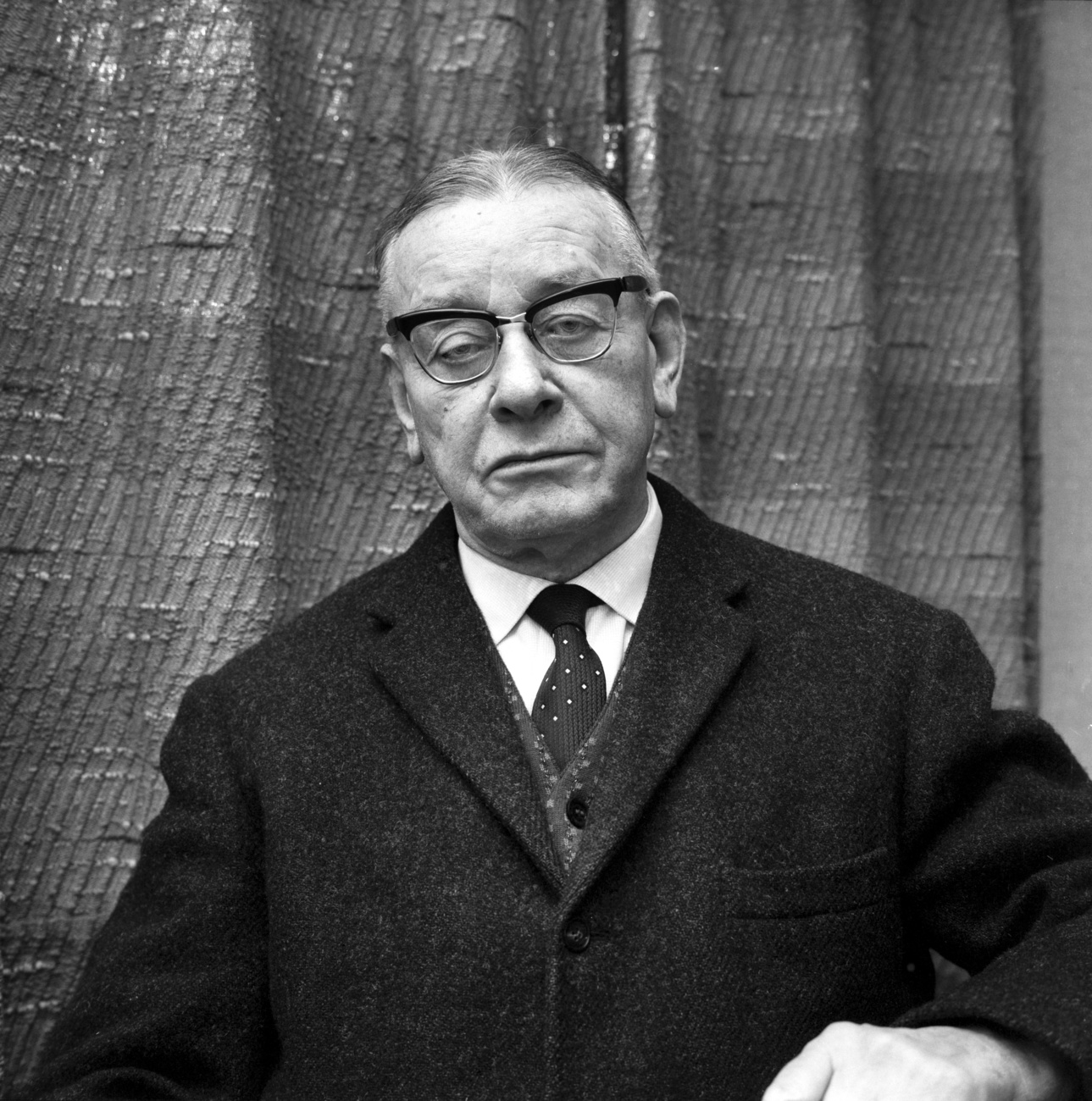

Swiss police commander Paul Grüninger, who died 50 years ago, saved thousands of refugees from being sent back to Germany before the Second World War – an action for which he was later convicted. He was exonerated only in 1995, thanks in part to the publication of a book, Grüningers Fall (Grüninger’s Case), by historian Stefan Keller.

In the 1990s, discussions about Grünigner triggered a debate over how to come to grips with Switzerland’s past. That decade also saw a dispute over dormant assets in Swiss bank accounts and the creation of the Bergier CommissionExternal link, an independent group of experts looking into Swiss actions during the Second World War. Similar questions flared up again in 2021 when the art collection of Emil Georg Bührle, who made his fortune selling arms to Nazi Germany, went on display at the Zurich Art Museum [Kunsthaus Zurich].

SWI swissinfo.ch spoke to Keller about how well Switzerland has been dealing with its past.

swissinfo.ch: Over the last 30 years, what has changed in the way the Swiss deal with their involvement with Nazi Germany?

Stefan Keller: I’m not sure whether that much has changed. The controversy around the Bührle Collection has shown that history is repeating itself: just like before, there is denial, trivialisation and defamation. People are still under the impression that after the Second World War, chaos ruled everywhere while law and order prevailed in Switzerland.

More

Israeli street named after Swiss who saved Jews

SWI: But in the 1990s there were a few significant achievements. Paul Grüninger was exonerated after the publication of your book, and in 1998 Switzerland exonerated Maurice Bavaud, the student who tried to assassinate Adolf Hitler in 1938 – 42 years after Germany did it. A lot was happening at that time. Why?

S.K.: With the end of the Cold War, old political lines shifted and there was a new way of thinking.

This could be seen in how archives were being handled, for example. For a long time, people thought that files were kept with the aim of protecting the state. Archivists would tell the authorities whenever a historian or a journalist wanted to look at a sensitive file.

In 1938 and 1939, the St. Gallen police commander Paul Grüninger saved hundreds, maybe even thousands, of Jewish people and other refugees, who under Swiss law should have been sent back to Germany. In spring 1939, Grüninger was dismissed without notice. At the end of 1940 the St. Gallen municipal court sentenced him to a fine following a lengthy investigation. He never found another job and died in 1972 in poverty and isolation.

In the last few years of his life, Paul Grüninger did receive some recognition for his deeds. For example, he was named one of the Righteous Among the Nations by the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial centre in Israel in 1971. However, it was not until 1995 that the St. Gallen municipal court reversed its 1940 verdict and acquitted Grüninger. The decision was brought about by Stefan Keller’s book, Grüningers Fall (Grüninger’s Case), a report by law professor Mark Pieth, the tireless legal work of St. Gallen politician Paul Rechsteiner, and the efforts of the association Justice for Paul Grüninger.

Grüninger’s case was the first exoneration of its kind in Switzerland. Later, a law was passed that exonerated all those who were convicted of helping refugees. Another law exonerated all convicted volunteers who fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Reparations – of a symbolic kind, at least – were also given to persecuted Yenish and those who, as children, were victims of Switzerland’s forced labour policies (“Verdingkinder”).

In 1997, the Geneva Archives wanted to give me just a summary of the file on a particular refugee who was extradited to the Gestapo in 1938. The refugee, who was still alive, had given me permission to inspect his files, but the archivist refused to let me have a look. She was worried that the man would file for damages. But once I hired a Geneva lawyer, she sent me a copy of the file.

This archivist was of the old generation. But for some time now, a new generation of archivists have been committed to shed light on the facts. They were very helpful to me – they knew the records well and they wanted to provide access to them.

SWI: Why did it take so long?

S.F.: The myth that Switzerland survived the Second World War on its own merits and with dignity and that it was one of the victors was always fragile. People knew all along that it was not true. But this myth prevailed for a long time as the idea of a “spiritual national defence” [a movement aimed at strengthening the values and customs perceived to be “Swiss” and creating a defence against totalitarian ideologies] among all social classes muted social conflict during the post-war period. As late as 1989, the Swiss army organised a big event dubbed “Diamond” for the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the war – as if there was a reason to celebrate any aspect of the war.

More

New study claims Swiss rejected fewer Jews during Nazi era

For a long time, the fact that European Jews had been exterminated was not a big issue – not just in Switzerland but internationally. When the seminal book The Destruction of the European Jews by the American historian Raul Hilberg was first published in 1954, it went unnoticed. The term “Holocaust” became commonplace in Germany only when an American TV series of the same name was broadcast in the 1980s. The Hebrew word “Shoah” is a synonym for the extermination of Jews and it’s the French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann who introduced it to Europe when his film Shoah was released in 1984-85. It took a long time to perceive the systematic eradication of the Jews as a rupture of civilization in human history.

Even though the injustice of sending thousands of people back to their deaths – just like doing business with the Nazis – was repeatedly debated in Switzerland, it didn’t enter the mainstream for a long time.

SWI: When did it start?

S.F.: In 1957, Carl Ludwig wrote a report on refugee policy commissioned by the Swiss government. It was relentless and is still used as a reference today. Based on Ludwig’s report, Alfred A. Häsler published his legendary book The Lifeboat is Full ten years later. Häsler used information from the archives of the Association of Swiss Jewish Refugee Aid and Welfare Organisations for his book and researched many individual cases. In 1973, Swiss television showed the series “Switzerland at War” by Werner Rings. It was extremely popular, which was surprising, as Rings himself came to Switzerland as a refugee. Several documentaries and newspaper articles appeared. Journalists and filmmakers played an essential role in helping the Swiss come to terms with their country’s involvement in National Socialism.

SWI: What advantages does journalism have in this type of work?

S.F.: Academics were slow to wake up to what was happening, and that made journalists realise we shouldn’t wait for them. Journalists know how to personalise stories, so people will understand – numbers are often too abstract. Was it 25,000 or 30,000 people who were sent back to Germany? It’s sometimes difficult to grasp the sheer size of numbers. But if you know two or three personal stories that are told by a real person with a face, a name and an address, you can understand their plight so much better.

More

How a Polish envoy to Bern saved hundreds of Jews

SWI: You didn’t just write a book about Paul Grüninger but with the help of lawyers you took the case to court and he was found to be innocent in a retrial. Why did you do it? Does it make sense to exonerate a dead man?

S.F.: We did it for his family, for the refugees who owe him their lives. It was symbolic politics. I think it’s important to set a good example. When we were fighting for Grüninger’s exoneration, the [municipal] court in St. Gallen initially told us that under [local] law, exoneration was a foreign concept.

SWI: The lawyer Stefan Schürer says Grüninger’s exoneration was a lesson learnt for mixing law and history. It was the first time that history was placed above the law.

S.F.: At no time in history has it been right to send people to their deaths. The lawyer for Grüninger’s family, Paul Rechsteiner, and the law professor Mark Pieth worked out the legal arguments for the case. In his report, Pieth even said that those who obeyed the orders of the government and those who issued them should have been punished. An order to hand people over to their murderers is always unlawful and must be refused.

SWI: What was the reaction?

S.F.: It was an explosive message that still applies now and will continue to in the future. Law and order must not contradict basic human rights. At the time, we believed that Grüninger’s exoneration would open a new chapter in how Switzerland deals with its past. But just as we had won the case, the debate around dormant accounts in Switzerland came to the fore and there it was again, the defensive attitude of the Swiss. Swiss banks were accused of holding on to money that belonged to Jewish people who had been killed and refused to pay it out. We spare no effort to hunt down shoplifters, but when it comes to returning Jewish assets, we seem to turn a blind eye to who owns what.

To me, the reluctance to accept Jewish demands for compensation is anti-Semitic. I feel the same about the Bührle Collection at the Zurich Art Museum [Kunsthaus Zurich]. The paintings on display were owned by Jewish people and were bought with Nazi money. This should have set off alarm bells within every respectable citizen. But the Swiss still think they are innocent. They even built a museum for Bührle, an arms dealer.

Translated from German by Billi Bierling

More

Coming to terms with a tarnished Swiss wartime record

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.