Young and jobless? The solution isn’t always university

Over the last 20 years, the number of university graduates has been steadily rising all over the world. That’s true in Switzerland, too, although historically fewer people in the Alpine country have pursued higher education than elsewhere in Europe – and more are employed. What do the numbers tell us?

Higher education is no longer the selective and elitist system it once was, but a global mass market. The proportion of adults with tertiary-level (or university) qualifications rose by more than 10% between 2000 and 2011 across member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD):

Recent government moves have shown a belief in the close relationship between education, employment and earnings. Over the last several decades, governments worldwide have improved higher education opportunities for their citizens by increasing university funding and harmonising the university degree system, such as under the Bologna system in Europe.

And the reasons to do so are compelling: On average, across OECD countries, 4.8% of individuals with a tertiary degree were unemployed in 2011, compared with 12.6% of those lacking a secondary education. When it comes to income, the average difference between earnings from employment between low-educated and highly educated individuals was 75 percentage points across OECD countries in 2008.

Are there limits?

If fostering higher education has been beneficial to both individuals and countries’ finances, is there an enrolment rate limit? Too many highly educated young adults would cause a mismatch between the skills they have and what the market needs, leading to them not finding a job or taking up jobs for which they are over-qualified.

According to the International Labour OrganizationExternal link, the average incidence of over-qualification in developed economies was 10.1% in 2010, an increase of 1.6 percentage points since 2008. Furthermore, with increasing demand for higher education, costs have been steadily rising and shifting more from public to private or student funding sources, creating financial strain on young people who invest in higher education without reaping any financial benefits from pursuing their studies.

This question is especially relevant when considering the ubiquitous increase of higher education and the wave of youth unemployment that has hit Europe since the 2008 financial crisis (over 50% in Spain and in Greece).

Greece, Spain and Portugal are clearly struggling with youth unemployment, in contrast to Switzerland, Germany and Austria which have so far been spared. The most obvious explanation for the youth unemployment difference between these two groups of countries is their general economy. Spain, Greece and Portugal have been hit more importantly by the eurozone crisis. However, persistence of youth unemployment in many EU countries, in Spain for instance before the crisis, implies that economic growth alone will not fix the youth unemployment problem. One can note also that Germany, Austria and Switzerland are the three countries where an apprenticeship system is the most prevalent.

The relationship between education level and unemployment

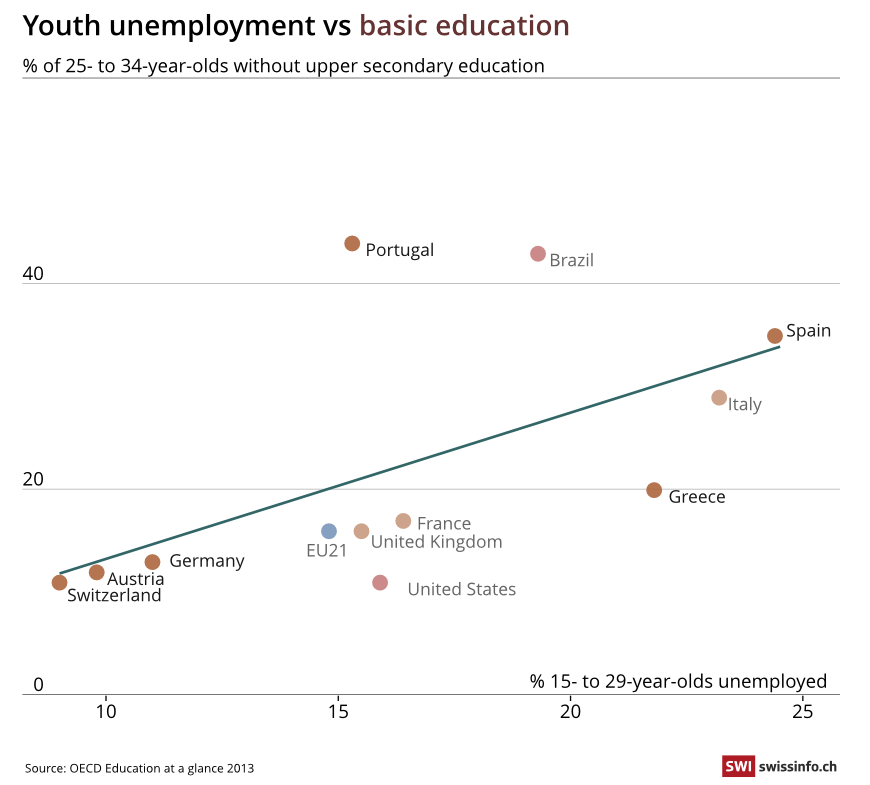

So, can the adage that higher education leads to a better chance of being employed be verified when comparing countries? If that were the case, countries with more university graduates would have less youth unemployment. The correlation between different education levels and overall youth unemployment are shown below for some countries based on 2011 OECD data. Unemployment is measured accurately considering youth unemployed as Not in Education, Employment, or Training (NEET).

The chart below shows no clear correlation between the number of young people with a university degree and overall youth unemployment. Quite the opposite, actually: Germany and Austria are among the European countries with the least number of university-educated youth but they boast a very low youth unemployment rate.

So are apprenticeships the answer, given that countries like Germany, Austria and Switzerland have been relatively immune to spikes in youth unemployment and are also the places with the most developed apprenticeship systems?

From a first glance at the chart below, it may seem that upper secondary education (i.e. apprenticeships or general studies to prepare for higher education) shows a weak correlation with youth unemployment. In Austria, Germany and Switzerland, half or more of all young people reached that level of education. However in Italy and Greece, upper secondary education is also widespread, but youth unemployment is still elevated.

Upper secondary education could involve general studies preparing for university as well as apprenticeship, and it is unfortunately impossible to separate these two paths from the data. But, according to the OECD in 2009, about three-quarters of the graduates whose highest level of education was upper secondary in Switzerland and Austria followed the apprenticeship route instead of the general academically based education. In Greece, a similar figure came in at around 30% and in the United States, close to 0%. In those countries, the apprenticeship system is less valued in the workplace than in the Austrian, German and Swiss labour markets.

There is, however, a correlation between the percentage of youth who did not attain upper secondary education and youth unemployment. Once again, Switzerland, Germany and Austria are unique here – they’re the European countries with the least number of young people who only completed mandatory school.

In the end, giving youth any form of further training and education beyond compulsory school appears to be critical in tackling youth unemployment. If higher education became a mass market over the past few decades, vocational education provides a clear alternative, as initiatives by some governments show. For example, the European Union recently launched a series of vocational-based initiativesExternal link to tackle youth unemployment, such as requiring structural reforms for apprenticeships and vocational education for its member states as well as favouring European mobility for apprenticeships.

And the World BankExternal link has bought into the trend as well: “In cross-country comparisons it is generally found that countries maintaining a substantial dual apprenticeship system, i.e. Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland, exhibit a much smoother transition from school to work… low youth unemployment and below average repeated unemployment spells than other countries,” it has written.

Although Switzerland can be proud that other countries are shaping their vocational programme model according to its system, the higher education bug is also biting in the Alpine country. Due in part to the increase in university graduates in Switzerland as in the rest of the world, apprenticeships are becoming less and less popular, especially in certain technical sectors. And the number of young people pursuing vocational training in Switzerland has not increased since 1986.

Based on international standards, adult education can be classified into three groups:

‘below upper secondary’: compulsory education achieved

‘upper secondary’: post compulsory education, starting typically at 15 or 16 years. It includes vocational training as well as general studies to prepare students for university (A-levels in UK, baccalaureate in Switzerland)

‘Tertiary/higher education’: university, college, University of Applied Sciences

Youth unemployment and youth education levels were measured for different age groups. However, youth education level percentages varied only slowly over time.

Additional country members of the OECD could have been added to this analysis. This was done and did not impact the big picture. For readability reasons, only a subset of countries were chosen.

Although education levels across countries could be classified in three groups, there are important differences in countries’ requirements and policies for each of the three education levels (in particular for apprenticeships).

With input from Veronica DeVore

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.