A blessing and a curse: the strength of the Swiss franc

In times of crisis, international investors often bet on the Swiss franc. Its reputation as a stable currency can be traced back to a policy that has often put currency stability before the interests of exporters.

Hip-hop songs about the US dollar are legend. Since the financial crisis of 2008, another currency – the Swiss franc – became popularised in song as a symbol of wealth alongside cocaine, champagne and Mercedes cars.

American R’n’B singer Ryan Leslie devoted a whole song to the Swiss currency in 2012. Set to opulent beats, the music video for Swiss Francs features Leslie driving his Porsche along the Zurich lakeshore and rapping in front of the Grossmünster cathedral about his Swiss francs in a Swiss bank account – a show of his imagined success.

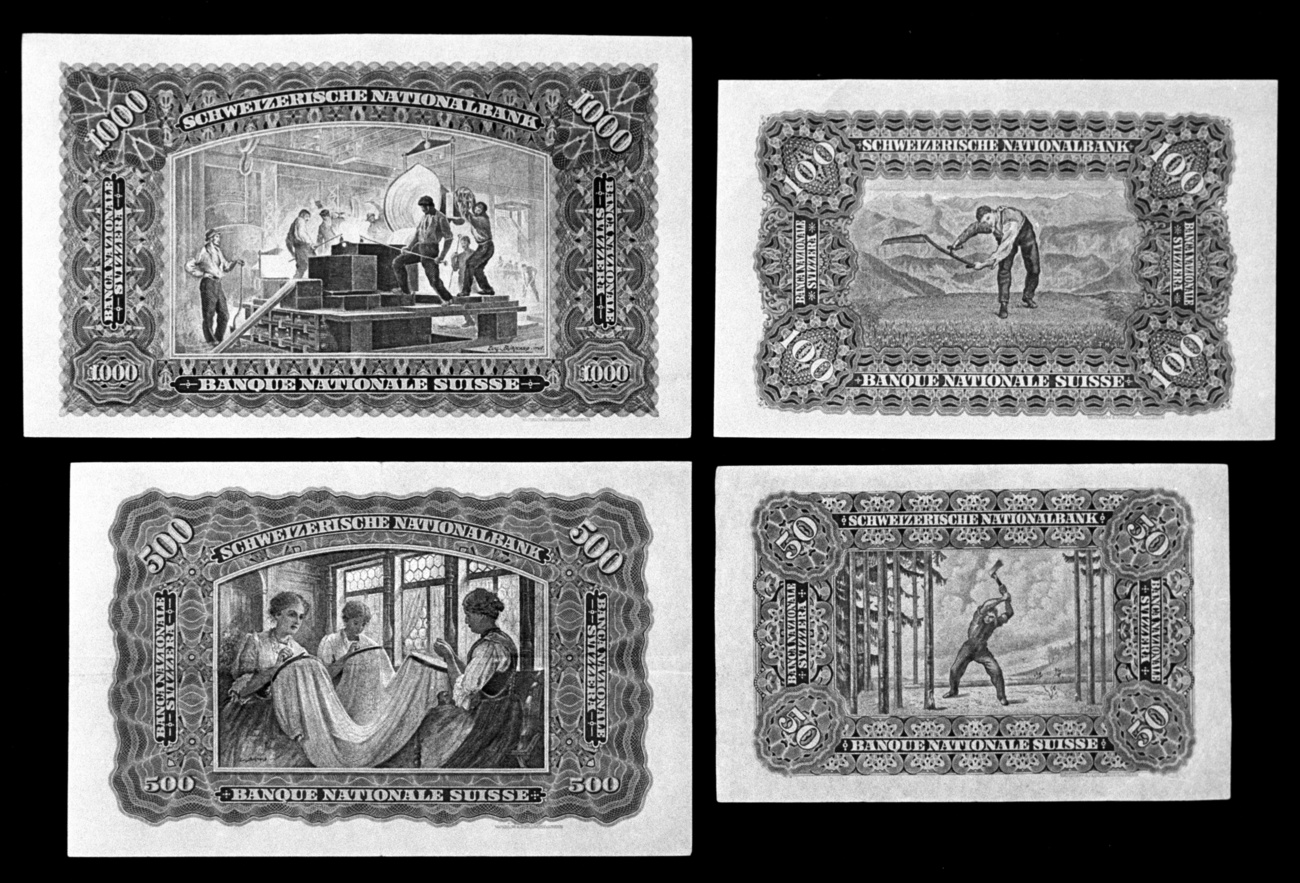

When the franc puts in an appearance in pop culture, it’s rarely this glamorous. Its development as a currency, however, is impressive. In 1914 a US dollar was worth more than CHF5; today it is worth less than a franc. One British pound sterling in 1914 was equivalent to CHF25 but today it is worth just CHF1.10. In the last two years the Swiss franc has coped better with inflation than many other currencies have done.

‘Holy war’ for a stable currency

As a young currency, the Swiss franc was overvalued. Shortly after it was introduced in 1848, the franc would often be melted down because the silver was worth more than the currency’s nominal value. The franc took some time to distinguish itself as a currency and was considered nothing more than a feeble offshoot of the French franc.

“The franc tended to be weak in the 1880s and 1890s because of the lack of a consistent monetary policy,” says historian Patrick Halbeisen, who heads the Archives of the Swiss National Bank (SNB).

This consistent monetary policy arrived in 1907, when the SNB started operating as the country’s central bank. It had the power to open the floodgates for money production and close them again. Its decisions still shape the franc today.

In its early years, the SNB kept to the international gold standard. This meant that the value of bank notes issued had to be covered by a fixed amount of gold in the vaults of the SNB.

The fact that Switzerland was spared during the First World War was the first step on the Swiss franc’s road to joining the league of strong currencies. The franc became a go-to currency in a crisis, a safe haven for assets.

Following the 1929 crash, all currencies started to tumble in value. In Switzerland the SNB maintained the gold connection, and the franc stabilised. But this put pressure on the nation’s exporters.

In 1936 only three nations still maintained the gold standard: France, Switzerland and Holland. Finally the federal government issued an emergency decree to reduce the gold coverage for the Swiss franc.

Historian Halbeisen sees this long hesitation primarily as an expression of a mentality fixed on the gold standard. “They couldn’t imagine a stable monetary policy that wasn’t based on gold,” he says. “The SNB wasn’t alone in this. It was just that other central banks succumbed to market pressure and gave up the gold standard.”

Although the economic results were good, outside the central bank many were sorry to see the gold standard go. The newspaper Finanz-Revue spoke of a “national tragedy” and an “economic coup”. Ernst Laur, a high-profile leader in the farming sector, waxed lyrical about the gold standard: “Mother Helvetia… had to give up her place of honour, the place of faithful trust… Yes! That would have been a mighty deed… if our currency had remained the fixed pole which all the currencies of the world had to acknowledge.”

Fritz Leutwiler, who headed the SNB from 1959 to 1974, later described the central bank’s support for a stable currency and the gold standard as a “holy war”. In the monetary system of fixed exchange rates that prevailed after 1945, the US dollar became the reserve currrency – but it was still tied to gold. Switzerland adhered strictly to the standard up until the end of the 1960s. Leutwiler saw this as monetary “fair play”.

A currency whip

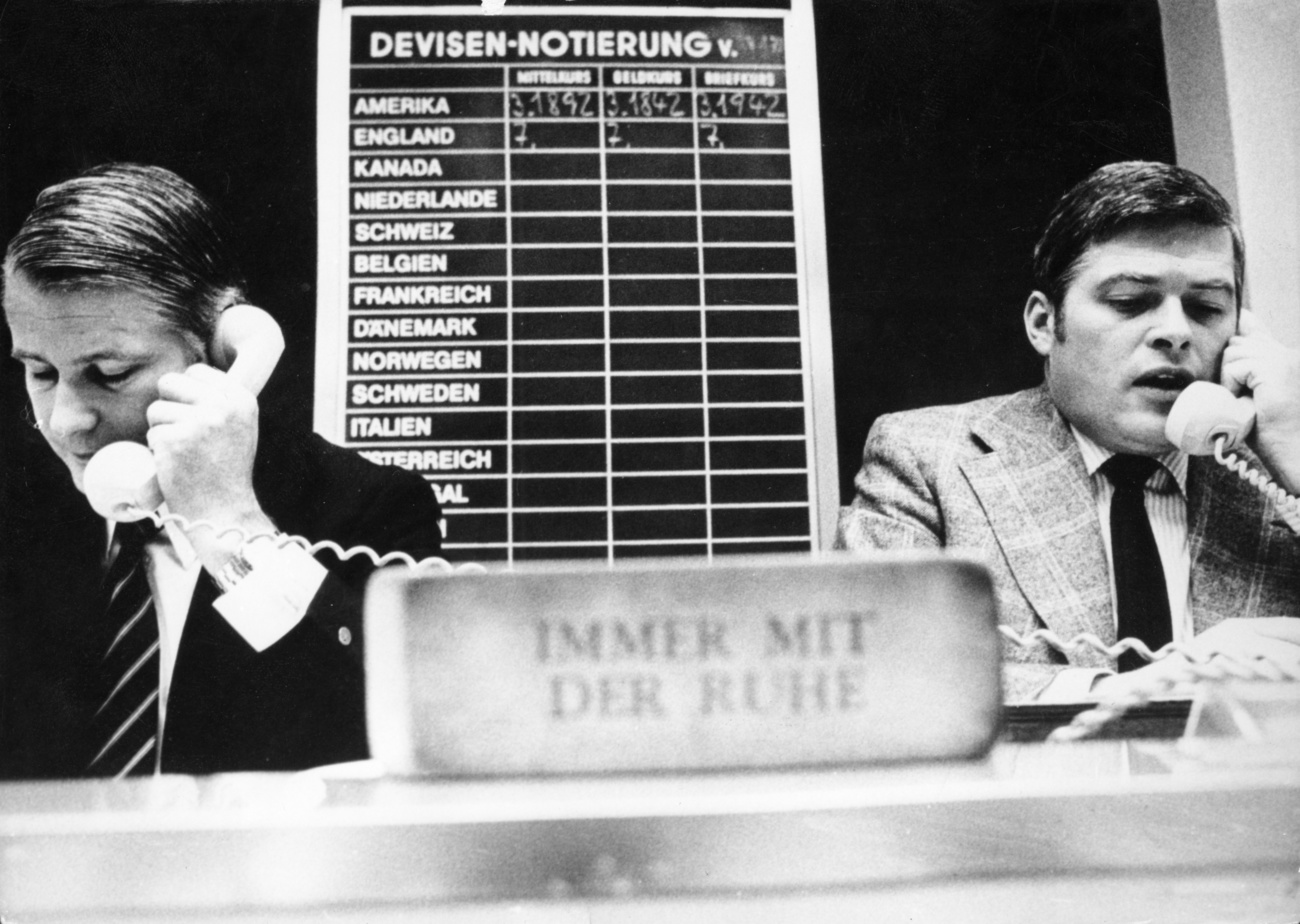

By the end of that decade, it became almost impossible to maintain the fixed-exchange rate policy. The dollar was tumbling in value, and the buying up of the Swiss franc could hardly be stopped. So in 1973 the SNB moved to a system of flexible exchange rates.

More

When the Swiss franc had to learn to float

The franc had nothing holding it back now. Along with Germany, Switzerland adopted a monetarist approach. It announced expected increases in the quantity of printed money. Inflation was now the focus of stabilisation efforts, not the value of the franc itself – and this drove it right up in value during the economic upheaval of the period. The collapse of the economy in Switzerland triggered by the oil crisis of the 1970s was thus more severe than it was in other countries.

The export industry shrank without precedent, with the textile sector taking a particularly heavy beating. Unemployment remained manageable, but only because 250,000 so-called “guest workers” who had been employed in Switzerland were told to go home.

In 1978 the SNB gave in and announced an exchange rate target to discourage the buying of francs. The currency was to be worth no more than 80 German Pfennigs (pennies) – a decision that calmed the franc market for years after.

Switzerland had a similar experience at the beginning of the 1990s, with controversy about this period still a point of discussion among economists today. Here too the SNB let the franc appreciate in value for a long time. Only in 1996 did it give the markets a target – and again exporters were suffering.

In reaction to the 2008 financial crisis, the franc rose in value again. In 2011 the SNB linked the franc to the euro. When the bank removed this peg in 2015, the value of the franc surged. This time the consequences for industry were less brutal. Enthusiasts for the policy praised the strong franc as a “currency whip” that would drive the Swiss economy to greater efficiency.

More

Why the strong franc no longer scares Swiss businesses

Daniel Lampart, chief economist at the Swiss Trade Union Federation, sees this differently. “Every phase of the surging franc led to painful job losses,” he says. In the 1970s it hit the watchmaking industry, in the 1990s the electrical and railway industries, and now it’s the turn of the food and machinery industries. “It keeps hitting icons of the Swiss economy. Toblerone goes east. The Matterhorn has to disappear from the Toblerone logo. The strong franc is never the sole problem – but the strong franc is eliminating many jobs.”

Lampart, who from 2007 to 2019 was a member of the Bank Council of the SNB, sees the central bank’s reluctance to hold down the franc as a basic mistrust of Eurozone countries: “The Eurozone – particularly with countries like Italy, Spain and France – was regarded as unstable and politically different,” he says. “There is a nationalist-conservative undercurrent here.”

He contradicts the pride in the franc by saying that it is not really all that important as a crisis currency. “The franc is important for the Swiss,” says Lampart. “Foreign investors invest in the franc just so as not to put all their money in the dollar and the euro. Or else they speculate on a surge in the franc when there is a crisis. Our currency is not all that central internationally.”

In spite of the perennial interest from investors, the Swiss franc will probably never hang from a gold chain around a rapper’s neck.

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.