Cinema confronts the fear of Islam

The Toulouse killings have reignited the debate on integration of Muslims in Europe. The issue is also being tackled by contemporary film-makers.

A dagger-toting, double-crossing villain with a moustache, a Middle-Eastern accent and an evil look in his eye: whether in literature or in the cinema, this has been the standard figure of the Arab “bad guy” opposed to everything good in the Christian West.

“This feeling of mistrust and fear towards an imaginary all-conquering Islam was accompanied by an idealisation of the Orient, taken from the Arabian Nights. The oriental lifestyle, the women’s seductiveness, the hospitality and the poetry exercised a peculiar fascination on Westerners”, explains sociologist Gianni Haver, who teaches at Lausanne University.

“At one time women with a veil were an emblem of sensuality, whereas today they embody the fear of Islam and its traditions.”

While the fascination with the Orient has lost some of its intensity in western cinema, the clichés linked to the Arab and Muslim world are still a feature of American TV series and blockbusters exploiting the spectre of terrorism or nostalgia for the colonial era.

From Europe, social criticism

European cinema has a very different tone. The presence of North African immigrants in countries like France, and the predominant role of art-house cinema, mean that the topic of Islam and its relations to the western world have increasingly become the focus of social criticism.

Written and directed to a great extent by second-generation immigrants, these films relate the other side of the Muslim presence in Europe: rebellion against colonial domination, taking refuge in religious identity, and the experience of discrimination and misunderstanding.

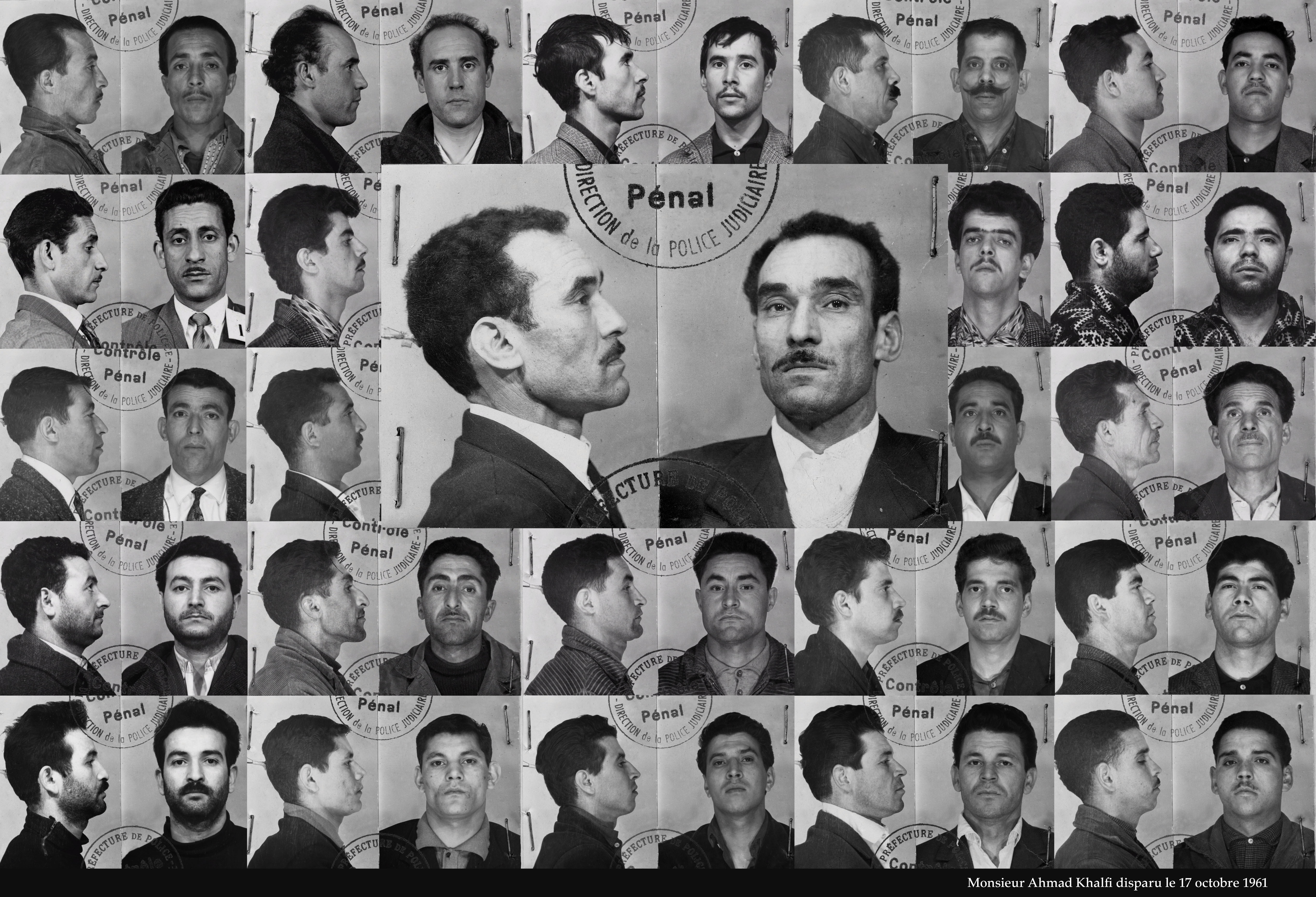

A good example is Yasmina Adi’s documentary “Ici on noie les Algériens” [Here we drown Algerians], which dramatises the brutal repression of Algerians in France in 1961, one year before Algeria achieved independence.

This is a film with a definite political and social cast, which the Fribourg International Film Festival recently decided to screen for the public in a section devoted to the image of Islam in the West.

“Apart from some feature films with a optimistic tone, these productions hardly get into Swiss cinemas, which are increasingly dominated by big-budget American movies”, explains Thierry Jobin, former cinema critic and artistic director of the Fribourg Festival.

“If we can safely assume that art-house cinema has a better grasp of remote cultures and traditions, this homogenisation of the market may well have considerable repercussions – not just from an artistic point of view, but also from a social and a political one.”

Reawakening of religious identity

“In recent years, in France, the climate has deteriorated badly. Religions – and in particular Islam – are stigmatised and exploited for the sake of winning votes”, Adi, who was born in France into an Algerian immigrant family, told swissinfo.ch.

“At one time people used to ask me what nationality I was. Today they just want to know if I am Muslim.”

Used as a bugbear by some political parties and media, transformed from a private matter into a public problem, the Muslim religion has become for many immigrants a place they can find their identity.

“Unlike Italian or Spanish migrants in the sixties, the North African refugees could not count on the help of trade unions or Catholic Church institutions. They found themselves isolated, stuck in a ghetto, and then they took refuge in religion as a means of collective identity”, says Mariano Delgado, professor and dean of the faculty of theology at Fribourg University.

“Today this Muslim identity is even stronger among the second generation and inevitably clashes with a European society which is trying to be more and more secular and perceives religious symbols as a provocation.”

Then again, there are people like Algerian director Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche who make fun of the clichés and use humour to tackle the complexities of religious morality and tradition. In “Dernier Maquis” [Last of the Resistance] – presented at the Cannes festival in 2008 and included in the Fribourg selection – the characters ask themselves what it means to be a “good Muslim”: praying several times a day? Learning the Koran by heart? Being circumcised? Wearing a veil?

These questions come back again and again in films about Islam and its relation to the West, as the film-makers emphasise the importance that their faith has in the daily life of many Muslims and explore the frontier that separates belief from religious extremism.

When faith leads to violence

In his most recent feature, “La Désintégration” [Disintegration], Philippe Faucon, a film-maker of Moroccan origin, explores the relationship between fanaticism and social exclusion.

It tells the story of three young immigrants with no work and no prospects, who are recruited by an Islamic extremist to blow themselves up with a car bomb at the seat of the United Nations.

Avoiding over-simplification of the issues, Faucon shows how faith can become a tool of violence.

“Monotheistic religions are an ambiguous phenomenon, with a dual nature”, says Delgado. “On one hand they have a claim to universality, as defined through the promotion of peace and justice. On the other hand, they are absolutist and may get carried away into violence, as happened to the Roman Catholic religion with the Crusades and the Inquisition.”

The opposition between good and evil which has its origins in the delicate political balance that has influenced relations between East and West for centuries is to be found in contemporary films too.

European cinema seems to have succeeded in freeing itself from stereotypes derived from the image of an Arab invader, but the subject of Islam is still a very loaded one. It continues to reflect the fascination and mistrust that haunt the collective imagination of the Western world.

The recent Fribourg international Film Festival (FIFF), devoted a special section to the image of Islam in the West.

Eight films were presented:

“Dernier Maquis”, by Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche, France/Algeria, 2008 (Swiss premiere)

“Hadewijch”, by Bruno Dumont, France, 2009

“Ici on noie les Algériens”, by Yasmina Adi, France, 2010 (Swiss premiere)

“La Desintégration”, by Philippe Faucon, France, 2011 (Swiss premiere)

“Le Destin (Al-massir)”, by Youssef Chahine, France/Egypt, 1997

“My Beautiful Landrette”, by Stephen Frears, Great Britain, 1985

“Pierre et Djemila”, by Gérard Blain, France, 1986 (Swiss premiere)

Switzerland is home to between 350,000 and 400,000 Muslims. About 12% have Swiss citizenship.

The number of Muslims in Switzerland has grown considerably over the last decades, in part because of people fleeing the war in the former Yugoslavia.

The percentage increased from 2.2% in 1990 to 4.3% in 2000, the year of the last federal census for which data have been published.

At present the percentage is estimated at about 4.5% of the population.

The majority of Muslims in Switzerland come from the former Yugoslavia (56%) and Turkey (20%).

An estimated 10,000 are Swiss converts.

In Switzerland there are four mosques that have a minaret (in Zurich, Geneva, Winterthur, and Wangen near Olten) and about 200 Islamic prayer houses, situated mostly within cultural centres.

In a nationwide vote on November 29, 2009, the people and cantons approved a constitutional change allowing a ban on building new minarets in Switzerland. The proposal was accepted by a majority of 57.5%.

This initiative was launched by a committee composed of members of the Federal Democratic Union and the Swiss People’s Party. The government, a majority in parliament and the Churches were all against it.

In March 2012 the Swiss parliament turned down a proposal put forward by the People’s Party to forbid persons with their faces covered to use public transport or to enter government buildings.

In canton Ticino, an initiative with similar wording collected 10,000 signatures and is to be put to a popular vote.

The People’s Party is weighing the possibility of launching an initiative of this kind at the federal level.

(Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.