SWISSCOY: more female recruits for more peace

Women are still a minority in international peacekeeping operations. The Swiss armed forces’ contingent in Kosovo, SWISSCOY, shows just how important their role can be.

Iris Probst walks over to us with a broad smile and stands to attention. The interview with the trainee peacekeeper takes place in her break between fire-safety training, a session on how to behave in crisis situations and a sports class. The smell of fire still clings to her clothes and hair.

As the conversation unfolds, we learn that the 29-year-old woman from canton Graubünden used to work as a journalist but now wants to learn more about security and peace. Already in her student days she was particularly interested in security and conflict prevention. “After this mission, I would possibly like to work in this field,” she says.

The training module Probst has just completed is part of her three-month pre-deployment preparation at SWISSINT, the Swiss armed forces’ centre for international peacebuilding in Stans-Oberdorf, in canton Nidwalden. After this, she will be posted to Kosovo for six months, as deputy press and information officer with the Swiss peace-support mission, SWISSCOY.

More

Swiss army seeks to recruit more women

Women play a growing role in peacekeeping

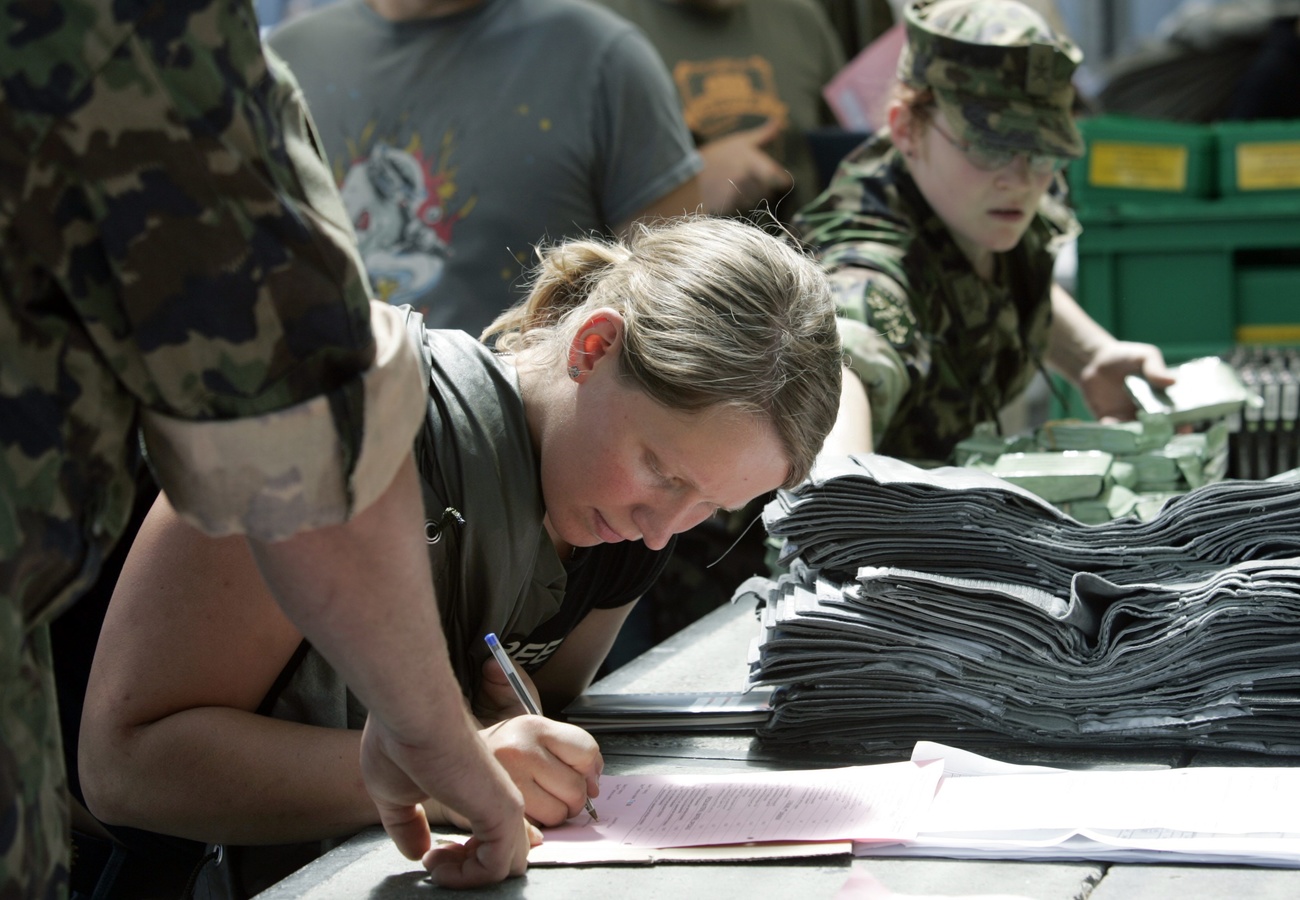

Probst does not stand out in Stans-Oberdorf. She is one of 27 women soon to be deployed to Kosovo with SWISSCOY. The proportion of women in the peacekeeping force has risen steadily in recent years. In 2020, around 60 women were sent on mission to Kosovo; by September 2022, this number had risen to nearly 70.

The SWISSCOY contingent comprises a maximum of 195 volunteers who want to contribute to peace and stability in Kosovo for a period of six months. Their backgrounds are as varied as their motives, explains André Stirnimann, lieutenant colonel in the general staff. He is the head of training at the SWISSINT centre and, as such, responsible for preparing Probst and her future comrades for SWISSCOY and other Swiss peacekeeping missions around the world.

“No other part of the armed forces is as diverse as SWISSCOY,” he says. “We have people with different life plans and values, from different professions, age groups and language regions and of different genders.”

SWISSINT is the Swiss armed forces’ centre of excellence for missions abroad. It manages some 280 officers, non-commissioned officers, soldiers and civilians deployed in more than a dozen operations in Europe, Africa and Asia.

SWISSCOY’s continuing involvement in the multinational Kosovo Force, KFOR, since 1999 has become a symbol of all Swiss peace-support operations. In that year, a Swiss government decision opened the door for Swiss participation in multinational peacekeeping forces under UN mandate for the first time.

SWISSCOY comprises a maximum of 195 military personnel, who carry out their duties in liaison and monitoring teams, the engineer branch, the military police, explosive ordnance disposal, the air transport detachment or the support detachment, or as staff officers. SWISSCOY’s budget for 2022 is CHF40.9 million ($40.9 million).

In January 2022, KFOR was made up of around 3,800 soldiers from 28 different countries (both NATO and non-NATO members). The force is charged with creating and maintaining a secure environment in Kosovo, monitoring developments in Kosovo and supporting international humanitarian efforts and civilian forces.

In other countries around the world, members of the Swiss armed forces are deployed as military observers, staff officers and demining experts with the UN, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the European Force (EUFOR), either individually or in small teams.

For several years, the entire Swiss defence ministry has espoused the gender-oriented perspective mentioned by Stirnimann. Under the slogan “A Swiss army for everyone”, the armed forces are seeking to promote diversity with respect to gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, language, ethnic and cultural affiliation and disabilities. The proportion of women attending recruit schools has been rising steadily. The latest summer recruit school, for instance, comprised 4% women, officers included.

Switzerland is also committed to ensuring that women play an increasingly active role in conflict prevention, peace processes and post-conflict reconstruction and reconciliation. The country reaffirmed this commitment with its national action plan for the implementation of United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 1325 “Women, Peace and Security”.

More

‘Vital for the future’: what our readers think of gender-neutral conscription

Women as an operational necessity

This goal has not yet been achieved, Stirnimann admits, and women are still strongly underrepresented in conflict prevention and peacebuilding – although it is a well-known fact that mixed teams achieve better results. Women are particularly indispensable in peace operations. “If we conduct a military operation within the local population and only send in a group of men, we exclude a large sector of society,” he says.

There are sometimes also cultural reasons why women need to be involved in peace operations. “In some countries, only women may talk to women,” Stirnimann adds. He is basically optimistic with regard to equality in the future: “Fifty years ago it was inconceivable that the teaching or medical professions should one day become a woman’s preserve – but today this is so.”

Probst is also confident: “This is certainly a completely new world for me. It takes time to get used to army life – not least all the military terms I didn’t know and that are ubiquitous here.” But she does not feel at a disadvantage compared to those men or women who have completed recruit school.

Who should adapt to whom?

During our lunch with Probst, we can see many men in the canteen kitchen serving meals to women in uniform. However, this scene cannot hide the fact that such assignments are practically impossible for many women because of family commitments. So how does the defence ministry plan to make peace missions more attractive to women and help reconcile the demands of family and career? Should women adapt to the military, or should the army also adapt to women?

“Of course, we strive to create the same conditions for everyone in peacebuilding, men and women alike,” says Stirnimann. “We cannot allow special treatment for a particular group, but, through our communication and thanks to the commitment of Defence Minister Viola Amherd, we are working hard to increase the proportion of women.”

This is valid not just for Swiss peacebuilding work, Stirnimann further explains, but above all for the militia army, although he does not name any specific measures being taken. “I believe that these missions abroad are an attractive offering, for both men and women who want to have a new experience.” Mothers, too, have been reporting for duty, he adds. “The issue of how to balance family and work is certainly a challenge in all fields. But we are observing the experiences of other countries and making progress here too.”

Exercises to overcome self-doubt

Many aspiring female peacekeepers must first overcome the apprehension that they are physically less strong than their male colleagues. Thus, during the training course, a slightly built woman is instructed to free a colleague twice her weight from a car during a rescue exercise: “But how is this possible?” the woman trainer asks rhetorically – before demonstrating how to do it with the right technique.

Kosovo, which today is almost exclusively inhabited by Albanians, was part of Serbia until 1999. After the Kosovo war broke out in 1998, NATO air strikes forced the Serbian state to withdraw from the territory. From 1999 to 2008, the province was administered by the United Nations Mission in Kosovo, UNMIK. Over 100 countries, including Switzerland, have recognised Kosovo’s independence. Others – including Russia, China and the five EU countries Greece, Romania, Slovakia, Spain and the Republic of Cyprus – have not yet done so. As a result, Kosovo cannot join the UN.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and heightened tensions between Russia and NATO have triggered fears of renewed violence in Kosovo, as Russia and the West are also vying for influence in the Balkans.

“After three months of training, we can often no longer see any difference between those women who have completed recruit school and those who have just done the basic pre-deployment training”, Stirnimann sums up.

Probst admits that, to start with, she was afraid she would not be accepted by her male colleagues; but this fear was quickly dissipated. The atmosphere at the centre is collegial and friendly and she feels well accepted. And so the future SWISSCOY member is still smiling broadly when we say goodbye in the evening – after a day of exhausting exercises in order to prepare for crises and risks abroad.

We leave the centre, which is committed, among other things, to bringing more peace to the world by including more women. We have also been invited to visit the SWISSCOY camp in Kosovo, to see Probst and her colleagues in action, and to see for ourselves what impact the Swiss peace strategy is having on the harsh reality on the ground amid the recent tensions in Kosovo.

Edited by Marc Leutenegger; translated from German by Julia Bassam.

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.