Rithy Panh revisits the horrors of the Khmer Rouge

Cambodian film-maker Rithy Panh talks about his latest film, Graves without a name, being shown in Geneva, which explores the lasting effects of the Cambodian genocide.

His documentary is competing in the city’s 17th International Film Festival and Forum on Human Rights.

Many of the director’s 22 filmsExternal link have dealt directly with Cambodia’s genocide and its perpetrators, including The Missing Picture (2013), Exil (2016) and his latest, Graves with no name.

His new documentary focuses on a 13-year-old boy, representing Panh, who has lost most of his family in the genocide and begins a search for their graves. He travels to Trum, a “village in the middle of nowhere” in Battambang province. This is where Panh and ten of his family members were deported in 1975, along with many other Phnom Penh residents. In moving scenes, Panh, one of only two genocide survivors from his family, carries out funeral rites for his relatives who disappeared.

swissinfo.ch: Graves without a name takes the form of a Cambodian funeral ceremony involving various rituals. What is the meaning behind this artistic expression of mourning?

Rithy Panh: My films are part of a continuous process. There is never an ideal moment to tell this kind of story. I always work with the same sense of apprehension, the feeling that I might have missed a key element. But I have matured, as has the subject of my last film, which I have been constantly thinking about for the past ten years.

This movie has a certain length, and has involved a different way of filming. It’s dense and needs the viewer’s full attention. I’m not seeking consensus. I’m very lucky to have partners who follow and support my work. This method of creating films is disappearing.

swissinfo.ch: Is today’s cinema-going public open to such documentaries?

R.P.: We live in a society that hardly remembers anything. Things happen so quickly. One day we talk passionately about issues driven by 24-hour news sites. Then the next day we move on to another topic. What do we retain from it all? Nothing. This is the emptiness that I’m trying to combat with my films. Right now, everyone manipulates everyone. There is no space for thought and reflection. A new form of totalitarianism and control is being imposed on us.

swissinfo.ch: Buddhism is an integral part of your latest film. Has this spiritual aspect become more present in your work over the years?

R.P.: It’s part of daily life in Cambodia, where Buddhism is enriched by animism. Living souls that we can pray to exist in the rivers, trees, rice fields and in the wind. Everything possesses an essence linked to spirits and rituals.

It’s not just a film about me. It’s a reflection on how we should continue to talk to the dead.

swissinfo.ch: Rituals carried out during Cambodian funeral ceremonies allow monks to help the dead leave their physical bodies. But in that way, it allows the living to rediscover a certain peace and space to continue living. Is that also one of the themes in your film?

R.P.: Facing death is a way of renewing yourself. You must respect death and listen to what it tells you. It’s a way of breathing. Today, we don’t really respect the dead any more. Look at how people have desecrated tombs in Israeli cemeteries. People don’t just attack individuals but also grave headstones. The Khmer Rouge used to tell their victims that they would reduce them to dust, leaving no trace of them.

swissinfo.ch: Some people have criticized the Khmer Rouge TribunalExternal link, established in 1997, as a Western initiative that is not especially relevant for Cambodian people. What’s your view?

R.P.: You need courage to try to ensure justice prevails after a genocide. When you reach such a level of destruction of humanity and dignity, international justice is always incomplete, slow and embroiled in endless political negotiations.

But I continue to defend the Khmer Rouge Tribunal that Cambodia has accepted. For the first time it recorded who the victims and their executioners were. You shouldn’t destroy the credibility of this act of justice, even though it was limited, and the results are questionable.

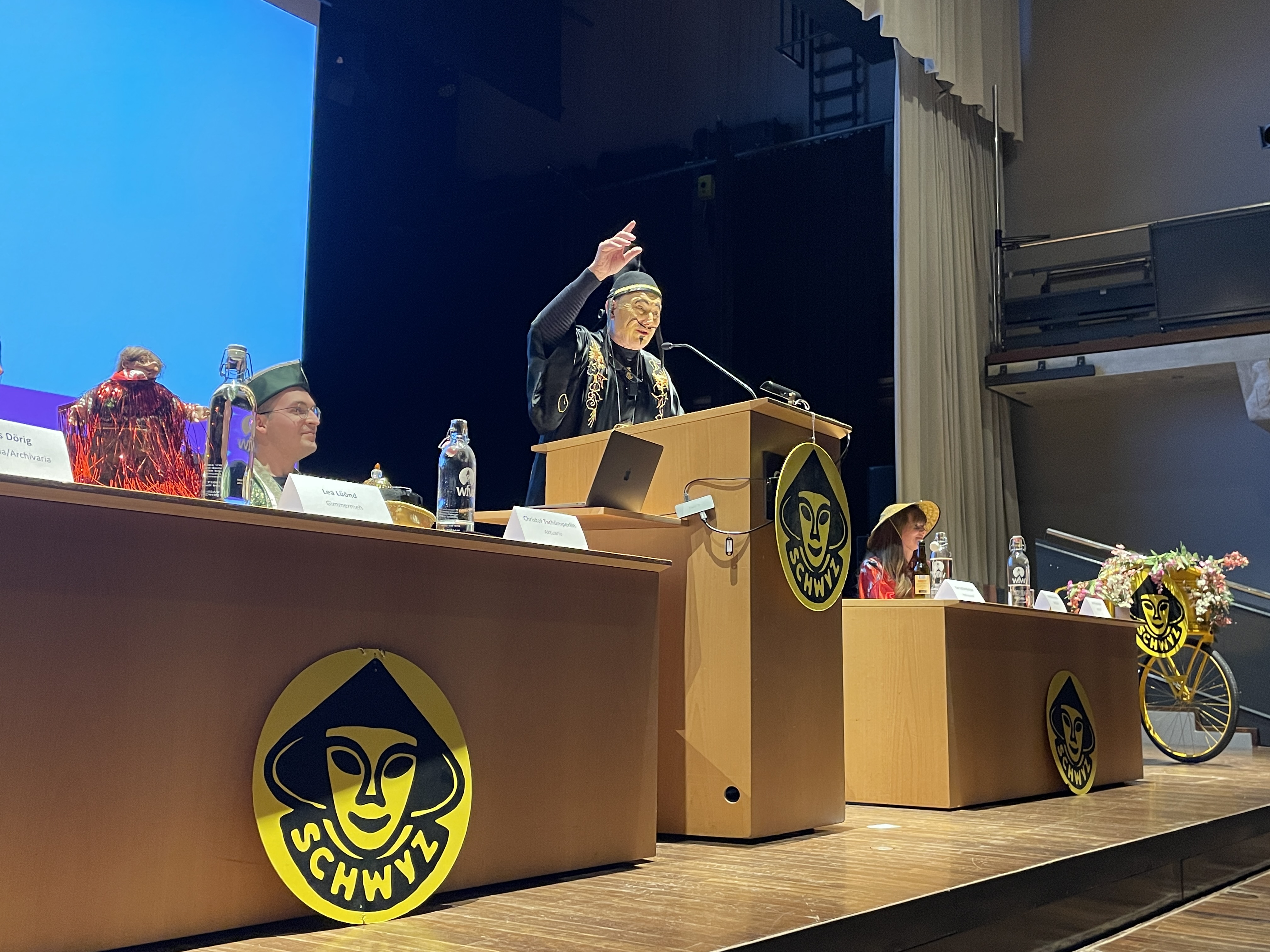

International Film Festival and Forum on Human Rights (FIFDH)

The FIFDH is a leading international film festival dedicated to human rights. For the past 16 years, it has taken place in the heart of Geneva, in parallel to the annual main session of the UN Human Rights Council in March and attracts some 36,000 people.

The 17th edition, which has a budget of CHF2 million ($2 million), runs from March 8-17 and features 47 films. As well as offering screenings, the festival organises debates on a range of human rights issues, some of which are discussed at the council.

The 300 guests this year included actors Forest Whitaker and Aïssa Maïga, artist Ai Weiwei, writers Roberto Saviano, Leïla Slimani, Laurent Gaudé and Uzodinma Iweala, filmmakers Rithy Panh, Petra Costa, Amos Gitaï and Fernando Perez Valdes and web creator Tim Berners-Lee.

Translated from French by Simon Bradley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.