Switzerland and Japan: contrary policies on nuclear power

The Swiss are voting on scrapping nuclear power just as reactors are coming back online in Japan, birthplace of the modern nuclear energy debate. Is direct democracy responsible for this topsy-turvy world?

Japan and Switzerland are both representative democracies. Both are industrialised nations with export-oriented economies. And in recent decades nuclear power has played a significant role in both countries. In 2010, nuclear power stations supplied around a third of both nations’ electricity requirements.

But it’s not only atoms that are split by the peaceful use of nuclear technology: so are modern societies. In Japan and Switzerland, millions of people have taken to the streets since the 1950s, when plans for the construction of the first nuclear power stations were announced.

U turns

A turning point came on 11 March 2011, when the strongest underwater earthquake ever recorded triggered a huge disaster off the coast of Honshu, the main Japanese island. The quake beneath the ocean floor led to a tsunami, which claimed 15,000 lives on the Japanese mainland and destroyed around 400,000 buildings. There was a partial meltdown in the reactors of the Fukushima nuclear generator located directly on the coast, 350 kilometres to the north of Tokyo. Thousands of people in the vicinity of Fukushima died, and hundreds of thousands were exposed to radiation. This was the greatest nuclear catastrophe since the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. The shock of the incident was felt far and wide, including Switzerland.

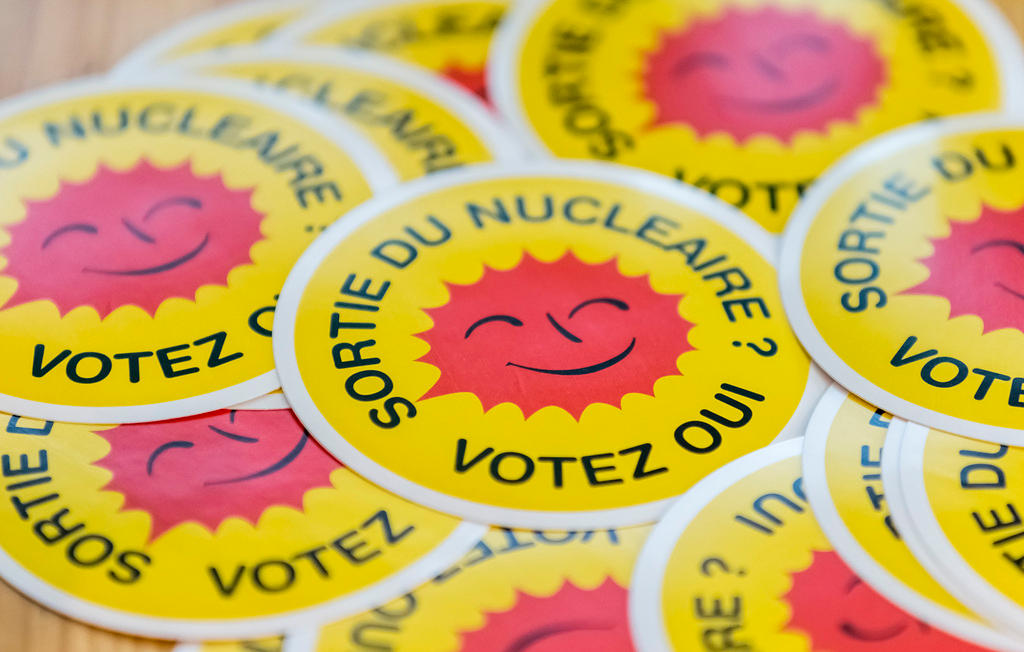

Just three days after the Fukushima nuclear accident, planning applications for three new nuclear power stations in Switzerland, which had been submitted in 2008, were put on ice by the Swiss energy minister Doris Leuthard. A few weeks later, the federal government initiated what has become known as the turnaround in energy policy. At its heart lies the Energy Strategy 2050, the objective of which is to abandon nuclear power entirely by 2050. And this is what the Swiss electorate will vote on in the referendum on May 21, 2017.

The situation in Japan is quite different. The government took all 48 nuclear power stations offline after the disaster. For a few years this industrialised nation of 130 million people got by with no nuclear power at all. However, under Liberal Democratic prime minister Shinzo Abe, Japan is now pursuing a turnaround in energy policy in exactly the opposite direction: in the next few years the proportion of the country’s energy requirement generated by nuclear power is set to return to over 20%, despite the fact that according to surveys, the majority of the Japanese population is against it.

One important reason for these diametrically opposed energy policies is the very different democratic rules of the game in Japan and Switzerland.

Here are the most important differences:

Republic versus monarchy: while modern Switzerland has never had a king, until the Second World War Japan’s emperor was seen as divine.

Federalism versus unitary state: Switzerland’s political system is based on the separation of powers at three levels – federal government, cantons and municipalities – while in the centralised Japanese state the prime minister wields enormous power.

Development versus protection: to this day, not least thanks to its long history of no internal strife, Switzerland manages without a constitutional court. In Japan, in contrast, democracy is subject to strict limits following the nation’s experience of fascism in the 20th century.

A nation united by choice versus a community of destiny: in contrast to Japan, where the culture remains highly homogeneous, the Swiss “nation” is based on the political will of diverse languages, cultures and religions.

Direct versus plebiscitary democracy: in Switzerland the electorate is the supreme decision-making body for central factual issues, while in Japan it is almost always the elected executive that has the final say.

Fully-fledged “nuclear democracy” versus no say in energy matters: the referendum on May 21 on the turnaround in energy policy will be the 15th national plebiscite External linkon energy policy in Switzerland since 1979. Japan has not had any at all on the subject in the same period.

Mandatory versus consultative referendums: at local level Japan also has forms of direct democracy, though popular decisions in referendums are merely consultative in nature – not mandatory, as they are in Switzerland.

In summary, citizens in Switzerland have far greater role in national energy policy decisions than their counterparts in Japan. This has a clear impact on nuclear policy, which in Switzerland – thanks to direct democracy – is far more representative than it is in Japan. Efforts in Japan to strengthen civil rights, citing representative democracy, have been repeatedly rejected.

Winds of change

The controversial energy policy of the current Japanese government under Prime Minister Abe is coming under increasing pressure from political and civil-society forces, who are calling for democracy to be reinforced.

The opposition points out that popular referendums on nuclear and security-related questions were held in the 1990s – though only at a local level and only of a consultative nature. In the summer of 1996, the small town of Maki on the east coast of the island of Honshu rejected the construction of a new nuclear power station by a clear majority. And a year later the electorate in the province of Okinawa (Japan’s most southerly island group) voted for the closure of the US military base established there after the Second World War.

Inspired by the experience of these referendums, many people are now calling for more civil rights. A proposal by Abe’s ruling Liberal Democrats could well open a window for reform in the near future. It wants to reform the Japanese constitution, which celebrates its 70th birthday this year and has never been revised. But a step like that requires something that has been the political norm in Switzerland since 1848: a mandatory national popular referendum.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.