Switzerland’s global status is in jeopardy

Three recent Swiss diplomatic controversies have raised questions about whether the small Alpine country can still be considered a moral voice in world affairs, one that traditionally has been said to punch above its weight.

Switzerland has always prided itself on being able to establish a place among larger countries because of its successful economy, historical neutrality and moral positions, including Geneva’s being host to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the United Nations Human Rights Council. The comparative advantage of Switzerland, particularly international Geneva, as a unique platform for discussions such as the Reagan-Gorbachev summit during the Cold War or the Syrian peace talks have enhanced the Swiss image in human rights and humanitarian issues.

But three recent controversies have challenged this identity in global affairs: the refusal to sign a treaty banning the future use of nuclear weapons; a decision concerning selling arms to countries in conflict; and a global compact seeking to govern international migration. While a justification for each of the decisions can be made, they raise questions about the future of the country’s carefully crafted identity.

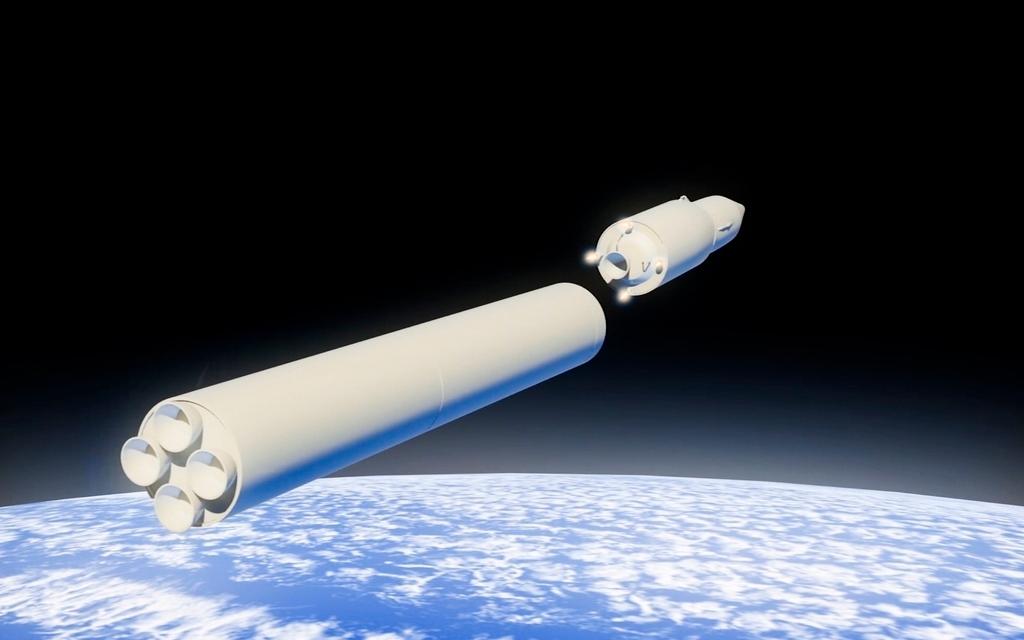

Nuclear weapons ban

On November 1, the First Committee of the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution supporting the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. More than 120 countries reaffirmed their support for the treaty, but Switzerland was not among them, nor was it one of the countries which signed the agreement.

The purpose of the treaty is clear and would appear to be consistent with Swiss policies:

“Each State Party undertakes never under any circumstances to: Develop, test, produce, manufacture, otherwise acquire, possess or stockpile nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices; Transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or control over such weapons or explosive devices directly or indirectly; Receive the transfer of or control over nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices directly or indirectly.”

In August, the Federal Council said External linkit is not in favour of signing the Treaty, a decision that was strongly criticized by Annette Willi, the president of the Swiss division of ICAN, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. (ICAN was the winner of the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize).

“The Swiss position on this question has an international implication,” Willi said. “As a Swiss citizen, one must ask…if we are in the process of living the end of the great humanitarian tradition of our country.”

In late October, the foreign affairs committee of the Swiss Senate also voted against Swiss adherence to the nuclear ban treaty, a further rejection of Switzerland’s humanitarian tradition.

Arms sales

A controversy over selling arms to countries in conflict has done nothing to improve Switzerland’s image. In June, Switzerland announced that it would allow the sale of arms to countries in the grip of an “internal armed conflict,” under certain conditions. The Swiss government said that “war materials” could be sold, but only if they were not used during an internal conflict. However, it added, “it should now be possible to grant export authorisation if there is no reason to believe that the war materiel to be exported will be used in an internal armed conflict.” The exemption “would not apply to countries plagued by civil war, like Yemen or Syria today,” the government said. Amid an outcry, the government has changed its position.

Although Switzerland is a neutral country, RUAG, its biggest arms manufacturer, had its highest-ever business turnover in 2017. Tension between business and values is never simple.

Amnesty International said of this tension: “Amnesty International Switzerland welcomes the recent decision of the Swiss government to stop the announced change of the national export control system, which would have allowed sales of Swiss arms to countries in armed conflict. This decision comes late and only after huge public pressure.”

Migration pact

Finally, the Swiss ambassador to the United Nations in New York, Jürg Lauber, has been co-facilitator of a United Nations Migration Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. Amid the horrors of recent mass migration catastrophes, Ambassador Lauber has worked with Juan Jose Gomez Camacho, Mexico’s ambassador to the UN, since 2016 to try to improve the treatment of migrants and to diminish the destabilisation of the countries receiving them.

In October, Switzerland’s Federal Council approved the United Nations Global Compact for Migration. The Council said that that the agreement corresponds to Switzerland’s interests in migration and its commitment to strengthening global migration governance. Ambassador Lauber said, “This text puts migration firmly on the global agenda. It will be a point of reference for years to come and induce real change on the ground.”

But on November 21, the Federal Council changed its position, announcing that Switzerland will not sign the document – which is politically but not legally binding – at an international conference in Morocco in December. Instead, the Swiss executive body put the decision on ice until parliament has debated the issue.

For the Federal Council, which is under considerable pressure from the conservative right Swiss People’s Party, the situation is not evident politically. In addition to parliament’s lack of a clear position so far, the government’s latest decision on the pact appears to discredit the work of its ambassador to the United Nations and his work as co-facilitator. Although countries such as the United States, Hungary and Austria have already said they will not sign the compact, a refusal by Switzerland to sign will be perceived as a Swiss affront to the United Nations and a rejection of its ambassador in New York.

Three controversies, three difficult decisions. What is clear in each situation is that the historic human rights/humanitarian tradition of Switzerland is now being contested in Bern. And that the moral position of Switzerland that has been a foundation of its punching above its weight is being eroded.

More

Government’s stance on nuclear ban under scrutiny

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.