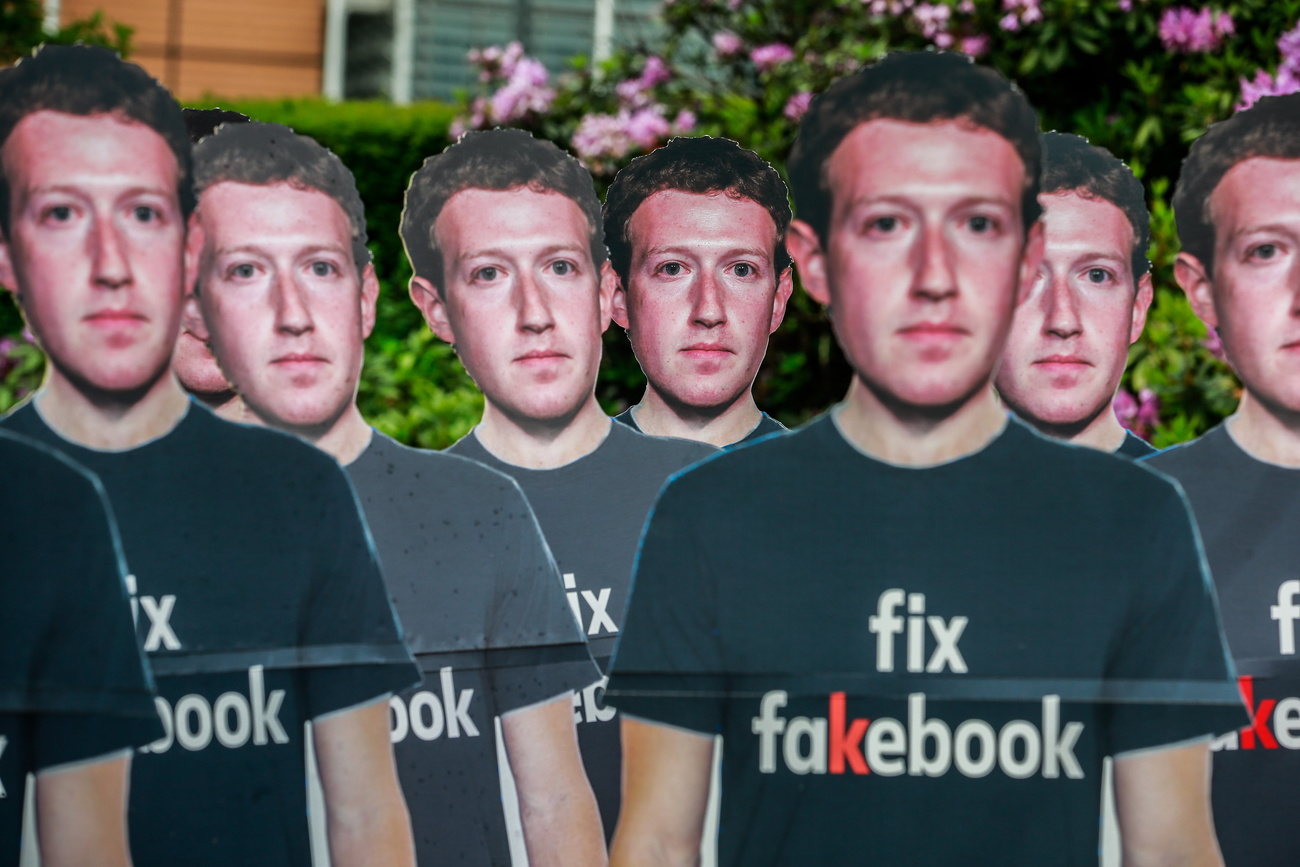

Does social media fuel fake news in Switzerland as much as in the US?

Switzerland is better protected against disinformation than countries such as the US. Is this because it has a better system and more circumspect citizens – or simply because fewer troll factories are interested in it?

Many people obtain information from social media instead of radio, television or newspapers. And many people are concerned that because of this, important news is missed, incorrect information is being spread more widely, and people are cocooned in their own filter bubbles, only receiving information that they have chosen to receive.

‘The most vulnerable country’

Unlike radio and television, social media is not bound by national borders. It is global. So it might seem logical to conclude that if social media drives fake news, disinformation and polarisation, it does so to the same extent all around the world. But that is not the case.

There are countries and regions that have fewer defences against online disinformation than others. The US is particularly exposed.

The study “Resilience to online disinformation: a framework for cross-national comparative research”, published by the University of Zurich in 2020, looked at various European countries and the US. It describes the US as a special case with regard to online disinformation.

The reasons are economic and structural. “The country stands out because of its large advertising market, its weak public service media and its comparatively fragmented news consumption,” the authors wrote. “The enormous size of its market – and its competitive and commercial culture – makes the US attractive for producers of disinformation targeting social media users.”

The study concludes that the US is “the most vulnerable country” to the spread of online disinformation.

Social media as a source of information?

Developments in recent years have, however, led to a greater awareness of online disinformation among many people internationally. According to the Reuters Digital News Report 2023, only 17% of users are still completely unconcerned about getting information via social media – the rest worry that they are missing out on important information or that their opinions are not being sufficiently challenged.

Many still use social media for news, but in some countries the share has dwindled. In Switzerland, every second person used social media as an information source in 2018, while in 2023, it is 39%. The US reached its record of 51% back in 2017; in 2022, the share was still 42%.

The percentages are higher in many African countries. In Nigeria, 78% currently use social media as a news source.

Social media has never been the decisive medium for forming political opinions in Switzerland: the 2021 reference book Digitalisierung der Schweizer Demokratie (Digitalisation of Swiss Democracy), for example, concluded that “a clear majority of Swiss voters do not consult social media to form an opinion ahead of elections and referendums”.

Radio, television and newspapers are still more important sources of information on politics in Switzerland. They are also more trusted.

Tobias Keller, a media and political scientist at research institute gfs.bern who worked on the book about digitalising Swiss democracy, told SWI swissinfo.ch that there are some factors that distinguish the situation in Switzerland from that of the US and Brazil. Mass media in the US have “much stronger political biases than in Switzerland – and social media fuels politically biased views”, he said. In Brazil, on the other hand, WhatsApp and Telegram are “very important information channels”. One-sided or false information is rarely exposed in this semi-public sphere.

According to Keller, the interplay of public and private media in Switzerland, as well as the multi-party system with its consensus-oriented politics, are factors in the country’s resilience to polarisation and populism on the internet, relative to other countries.

Digitalisierung der Schweizer Demokratie maintains that frequent voting serves as a kind of training for detecting disinformation. “Having assessed hundreds of political proposals and experienced hundreds of campaigns, Swiss voters are very accustomed to evaluating diametrically opposed information […]. This increases resistance to dubious information,” it said – regardless of the medium.

In other words, referendum flyers have already taught the Swiss that they cannot always trust information, no matter where it comes from. And they are aware that populism existed long before Facebook.

Populism in Switzerland – old news

Social media platforms are not only seen as purveyors of fake news – they are also frequently blamed for political polarisation and the success of populist forces.

For her dissertation, communications scholar Sina Blassnig from the University of Zurich examined how populist communication takes place on the internet. Among other things, she compared how often politicians from Switzerland, Germany, the US and Britain made populist comments on political talk shows and the internet. She also looked at the kinds of comments they made.

In her view, “certain features of the Swiss political system” that have often been seen as hurdles to populism are more conducive to it – such as the frequent referendums. “The regular referendums could in fact promote a permanent populist campaign and therefore offset the restrictive effects of the directorial and proportional representation system,” she said.

Blassnig said that although the entire political spectrum uses populist rhetoric “from time to time”, there is “a dominance of right-wing populism” in Switzerland, she said. But this populism is older than widespread internet usage. “Compared with other countries, Switzerland has had a strong right-wing populist movement since the 1990s,” she said.

More

Why people in Switzerland trust the state

Uninteresting Switzerland

Edda Humprecht conducts research at the University of Zurich and is the lead author of the study that identified the US as the country most vulnerable to disinformation.

In this study, Switzerland belongs to a cluster of northern European countries that have the highest resistance to harmful fake news. But for Humprecht, this is a product not only of democratic stability but also of its size, language divisions and low geopolitical importance.

Is Switzerland generally resilient to polarisation and populism, or is its resilience limited to social media as an accelerator of disinformation? “Neither,” Humprecht said. “Polarisation and populism play just as big a role as in many other countries. Social media is used widely in Switzerland. The country is merely less attractive for orchestrated campaigns.”

She agreed there are resilience factors, such as a well-developed media system. “But the strata that are susceptible to disinformation from the right-wing spectrum often don’t use the public media,” she said.

Humprecht sees social factors as more significant. “In Switzerland, the number of economically marginalised people is smaller than in France.” This contributes to a certain resilience, as does the small advertising market, she said.

In the study, Humprecht and her co-authors used advertising markets and thus profit orientation as a yardstick because this is easier to measure than geopolitical importance. “But geopolitics is just as important. Switzerland is in a good position there: it is less interesting for Russia or China to exert influence in Switzerland than in a large country.”

One reason why Switzerland is less threatened by fake news than the US is that Switzerland is simply not as interesting as the US.

Edited by David Eugster. Translated from German by Catherine Hickley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.