AI-generated rat genitalia: Swiss publisher of scientific journal under pressure

Researchers have criticised the Swiss open-access publisher Frontiers for publishing a scientific article containing incorrect AI-generated medical illustrations and misspelt words. The case sheds light on a business model that encourages the publication of research results at an unprecedented rate and at any cost.

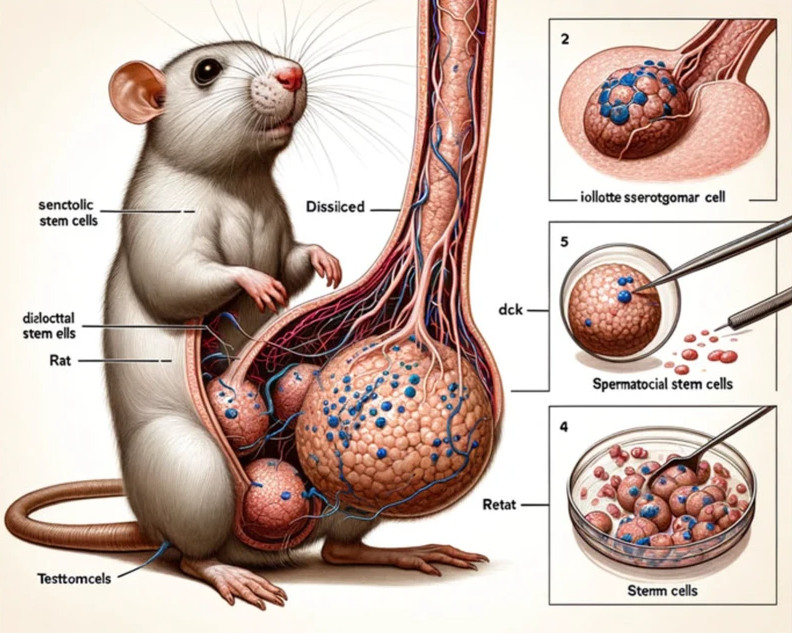

A scientific articleExternal link, published by Swiss publisher Frontiers in its open-access journal Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, raised red flags with researchers around the world for its misspelt text and nonsensical AI-generated images. One figure featuring a rat with huge, anatomically incorrect genitals caught the scientific community’s attention on social media. Scientists have made public the images and questioned Frontiers’ peer-review process.

Frontiers reacted by withdrawing the paper and thanking the scientific community on the platform XExternal link (formerly Twitter) for spotting the errors, stressing the importance of open science in collectively scrutinising incorrect research. Based in Lausanne, Frontiers has been publishing open-access scientific journals following the “pay to publish” business model since 2007.

We thank the readers for their scrutiny of our articles: when we get it wrong, the crowdsourcing dynamic of open science means that community feedback helps us to quickly correct the record.

— Frontiers (@FrontiersIn) February 15, 2024External link

Authors pay a fee ranging from under $100 (CHF88) to more than $9,000 – so-called article processing charges (APCs) – in order to get their article published in open-access publications and be freely accessible.

This model rivals more traditional journals that are based on paywalls and subscriptions. Large, prestigious scientific publishers – such as Elsevier and Springer Nature – have long controlled access to scientific knowledge, often funded by taxpayer money.

The world’s two largest open-access publishers, Frontiers and MDPI, both located in Switzerland, advocate so-called open science, advertising quick article review and publication times. The approach has raised concerns in the scientific community that the quality of what’s being published may be sacrificed for quantity to increase revenues.

Stefanie Haustein, a professor at the University of Ottawa specialised in open-access APC financing models, publicly voiced her concerns. “I’m worried that this is just the tip of the iceberg of how much false information has been published just trying to produce something quickly,” she says.

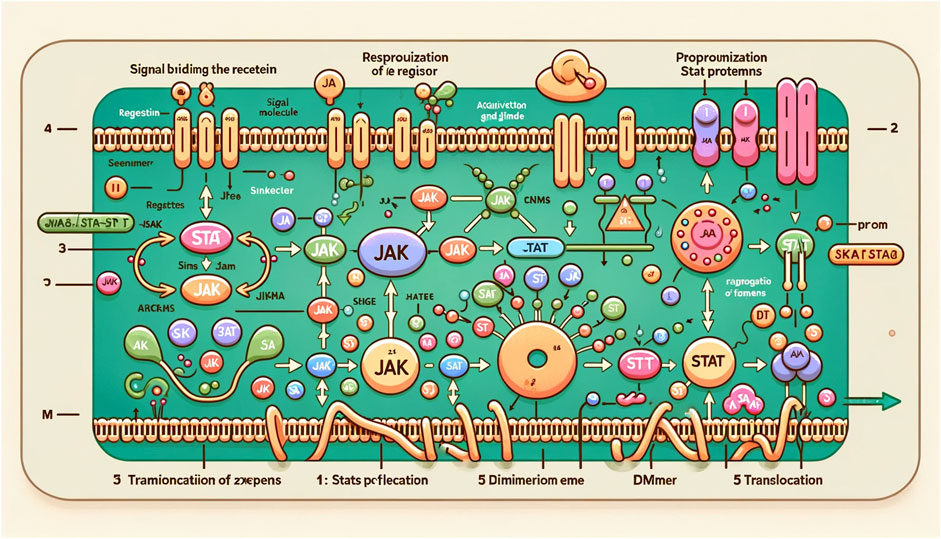

Researchers fear further risks to scientific integrity as publishers employ AI technologies in their review processes and authors use them to produce images and texts. Haustein thinks AI is not the main culprit behind the publication of low-quality research; instead, it’s a symptom of a system that puts researchers and reviewers under pressure to publish a lot, quickly.

‘Pseudoscience’

Contacted by SWI swissinfo.ch, Frontiers replied via email to the criticism that followed the publication of the article in Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. A spokesperson for the journal wrote that it was “an unfortunate and isolated incident”.

But this is not the first time that Frontiers has been at the centre of a storm for publishing articles of questionable scientific integrity. In April 2023, it published a paperExternal link with unsupported claims that face masks may cause Covid-19 symptoms. The paper was retracted a month later following massive criticism from scientists and public health experts.

The same fate befell an articleExternal link questioning the link between HIV and AIDS. This time, the publishing house tried to re-classify it as an “opinion” piece, before coming to the decision to retract it more than four years after publication. This and other similar cases prompted scientists to call for a boycottExternal link of Frontiers for its questionable review processes that allow for what some called “pseudoscience”.

Never submit to or review for a Frontiers journal! This thread exposes the dirt on their review process. They also killed Beall’s list, a quality control tool for publishing. And Frontiers allows pseudoscience, such as a “Neural Thermodynamics” issue I was recently asked for. https://t.co/ncLp5HqX6hExternal link

— Wei Ji Ma (@weijima01) August 7, 2021External link

Publishing at any cost

Frontiers nevertheless insists that it has “one of the strongest track records of quality in the publishing industry”, as a spokesperson wrote via email, citing that Frontiers is the third-most-cited of the large scientific publishers, with articles viewed and downloaded billions of timesExternal link.

But according to Haustein, the scandals involving Frontiers show that the primary goal of open-access publishers – spreading knowledge to advance science – has been corrupted by the business model underlying it. “The main goal is not to publish rigorous science but to be profitable and grow,” she says.

As evidence of this, she mentions that Frontiers charges authors an average of $2,270 (CHF1,992) for the articles it publishes, which doesn’t incentivise rejection. Frontiers’ rejection rate is far lowerExternal link than for traditional publishers: 56% versus 71% for Elsevier, for instance. Turnaround time is also extremely fast: authors can get a final decision on the publication of a submitted article in just 61 days, according to its websiteExternal link, when the average time among journals is three to six months.

An analysisExternal link also shows that open-access publishers are increasingly using “special issues” to publish the majority of their articles. “In the past the ‘special issues’ used to be something very rare and prestigious. Now they are used by Frontiers and MDPI as a growth model,” says Haustein.

In Switzerland, the spread of this practice led the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) to exclude researchExternal link published in special issues from its funding schemes. “The principle of ‘publishing at any price’ contradicts the policies of the SNSF,” a spokesperson told SWI swissinfo.ch via email.

Researchers and reviewers under pressure

With more researchers able to publish and access more freely available research than in the past, the number of scientific articles published has grown exponentially over the last decade. But the scientific community itself is not growing. Scientists are therefore expected to write, review and edit articles – often for free – at an unprecedented pace. And while researchers try to cope with an increased workload to advance their careers, scientific publishers’ profit marginsExternal link expand.

Frontiers has grown so large that it has essentially relinquished control over the editorial process, says Adrian Liston, a former Frontiers editor and an Australian immunologist at the University of Cambridge. Liston quit the company when he realised that it was practically impossible to reject a paper and that some editors were rushing the review process, overriding peer reviewers, to have the articles published as soon as possible and get the publication costs.

This is how he believes an article with incorrect AI-generated images could have been approved for publication, even if its authors clearly stated that they had used AI.

I quit as a Frontiers editor and refuse to review papers for them because of how difficult the journal makes rejecting a paper. You essentially can’t, you can only get stuck in endless reviewing loops. Still shame on everyone involved, but this is what the Frontiers system allows https://t.co/CxEzfYFd6GExternal link

— Adrian Liston (@LabListon) February 15, 2024External link

Generative AI in publishing is difficult to fight

The misuse of AI is not just a problem for open-access publications. Now that generative AI has entered the market and is able to write and produce images, scientists fear that it will become even easier for publishers and researchers to take shortcuts and cheat. As the technology evolves, the humans involved in the review process often find it hard to keep up.

“I think in universities we tend to ignore the power of technologies or often we simply do not have sufficiently good policies,” says Simon Batterbury, a professor in environmental studies who has been editing non-profit open access journals for years.

AI-produced fake data and images look so real that even experts have a hard time detecting them. “Even as a person using my expertise and software designed to detect duplications, I can no longer tell if these images or datasets are real or not,” says Elisabeth Bik, a microbiologist and scientific integrity consultant. The situation is so serious that a record 10,000 research papers were retractedExternal link last year.

More

Can ‘Plan S’ revolutionise access to science?

Academic publishers are fighting back by banningExternal link or placing various restrictionsExternal link on the use of AI in scientific articles. Frontiers considers it acceptableExternal link to use generative AI for writing manuscripts, but the authors must check for accuracy and declare the use of AI.

The Swiss open-access publisher is among those using AI in its editorial processes “to aid, improve and increase human ability to detect fraud and malpractices by researchers”, the company wrote via email. This is a way in which AI could help publishersExternal link curb the misuse of the technology in scientific papers.

But it doesn’t guarantee that bad science will be spotted, as shown by the case of the fake AI-generated images accepted by Frontiers. Nearly 25,000 researchers have signed the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, or the DORA agreementExternal link, to call for a solution to this problem. They argue we need to stop pushing researchers to publish as many articles as possible and seek publication by top publishers.

“We have to recognise people’s work, not just the journals,” Batterbury says.

Frontiers’ position on its process and standards

A Frontiers spokesperson provided the following information:

‘It is not “practically impossible” to reject an article submitted to Frontiers – our requirements for acceptance are rigorous and editors can only accept papers if they have received two independent reviewer endorsements.’

‘Frontiers is accredited by, and is a member of, major publishing regulatory and ethical organizationsExternal link, adhering to their quality standards and best ethical practices.’

‘The authors who created the AI-generated figures showing rats in their article were in clear violation of Frontiers’ guidelines. Peer reviewers requested revisions to the images, and the fact that the authors did not comply was missed during final quality checks. This was a genuine and very regrettable human error for which we have apologised.’

‘Poor-quality publications are not a consequence of open access. Like all other publishers, we encounter poor-quality and fraudulent researchExternal link and we retract following long-established processes in the publishing industry.’

‘Frontiers’ charges for researchers to publish an article range from $0 to $3,295, the average payment per article being $2,270.’

Edited by Veronica DeVore

This article was amended on May 13, 2024 to further reflect Frontiers’ position on its publishing practices. In addition, the following corrections were made:

Frontiers’ article rejection rate is 56%, not 48% as stated in a previous version of the article.

A Frontiers spokesperson said that the journal has “one of the strongest track records” in the publishing industry, not “the strongest track record” as stated in a previous version of the article.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.