How a Zurich music festival lit a spark for inclusion

Switzerland has pledged to promote the inclusion of people with mental disabilities in society, but progress has been slow. One music festival in Zurich is experimenting with a grassroots way to support inclusion and empathy.

Inclusion for people with cognitive disabilities

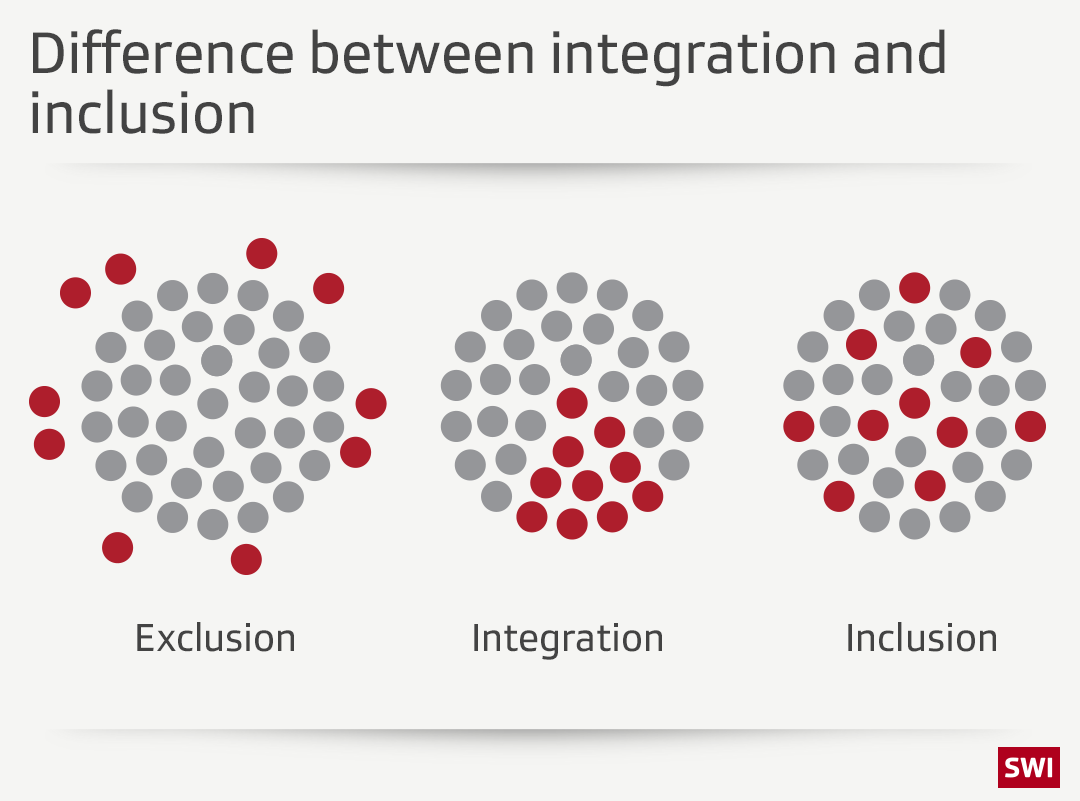

Inclusion means that people with mental disabilities can take part in society as equal members and that their differences will be perceived as an enrichment of society.

The concert hall at the Red Factory cultural centre in Zurich is full. The audience applauds, sings along and cheers on the performers. What seems like a typical, successful music festival is at a closer glance an effort to foster inclusion and empathy of people with disabilities.

On stage and in the audience, people with and without mental disabilities have come together to sing, celebrate and cheer each other on. Swiss singer Vera KaaExternal link takes the stage after the band Tobis Welt External link(Tobi’s World).

The latter recounts day-to-day life in a residential care home; for example, about how you can only find peace in the restroom. Or about holidays to Saas Fee which would be preferable together with a loved one — but without the presence of a guardian, who interferes at the most inappropriate moments.

The fact that Vera Kaa and Tobis Welt come on stage one after the other epitomises inclusion: both people with and people without disabilities are participating equally in cultural life.

This is one of the basic expectations of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with DisabilitiesExternal link, which Switzerland ratified in 2014.

But the “Soundsyndrom!External link” festival, taking place in Zurich for the second time, is still an exception. Switzerland is lagging behind when it comes to inclusion, says Andrea Brill of Tobias HausExternal link, a residential home for people with mental disabilities, which organised the event earlier this month.

“Switzerland is not living up to the commitments in the convention,” she says.

Room for improvement

A shadow reportExternal link on the implementation of the convention in Switzerland found several areas where people with disabilities face discrimination.

It states, “An inclusive Switzerland in which people with disabilities can live independently in all areas of life is still far off, despite a partial legal basis for this.”

Even the government concedesExternal link there is room for improvement when it comes to the participation of disabled people in all areas of public life.

Critics complain, for example, that disabled children are pushed into special schools,External link and that adults with mental disabilities don’t have the right to vote. According to advocacy organisations for the disabled, many adults with cognitive disabilities can’t freely choose their place of work or residence.

Andrea Brill says that other countries are much more advanced in terms of awarding state funding to disabled individuals, instead of financing homes and institutions. This kind of direct funding allows the person concerned to make his or her own decisions on whether he or she wants to live in a residential care home, in assisted living, or alone with the help of an assistant.

Where have all the disabled gone?

In the past, some Swiss families shielded mentally-disabled relatives from the public because they were ashamed or feared that they wouldn’t be respected or treated as equals. They worried they’d be “ridiculed as village idiots,” as Brill puts it.

Years later, special homes were founded to provide disabled people with professional care.

Although Brill works in a home for the mentally disabled and describes such homes as an important option, she also sees a big disadvantage in them: “People with mental disabilities are removed from day-to-day society and public life; homes create a kind of parallel society. It is similar with the elderly or end-of-life care.”

Mainstream society has become less accustomed to seeing people with mental disabilities. Many people forget how to interact and communicate with people with mental disabilities. There is the danger that, in the end, only their “deficits” are recognised and they are seen as a burden to society, particularly in a financial sense.

Brill can imagine that families hiding away mentally-disabled relatives will become an issue again in the not-too-distant future.

“Early diagnostics allow babies with disabilities to be aborted. I can imagine that sooner or later, health insurers will refuse to pay for a disabled child if the parents have decided against abortion despite a diagnosis. We are heading towards some difficult ethical questions.”

Using music and comedy

Tobias Haus aims to address the growing isolation of disabled people through a regular music festival for those with and without disabilities to come together not just as spectators, but also as performers. People with mental disabilities should be taken out of “the protective but also limiting walls of institutions” and have the opportunity to showcase their talents.

At the Soundsyndrom! festival (official trailer above), the audience learns first-hand, with plenty of comic relief from Tobis Welt, about everyday life for residents of a home for the disabled. Or from Hora’bandExternal link about how people with disabilities live in a society that is increasingly focused on fixed norms. These encounters promote empathy and prevent discrimination.

“The festival is an example of how it should always be,” Brill says. “I hope that it will become more matter-of-fact to encounter mentally disabled people everywhere in daily life.”

Switzerland and the convention on disability rights

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities aims to protect the freedom and rights of people with physical or mental disabilities.

Switzerland ratified the convention in 2014. It has not, however, ratified the optional protocol which means there is no legal recourse in cases where the convention is infringed. Switzerland does have to submit regular reports on how the convention is being implemented.

In the first report External linkin 2016, Switzerland reported that several legal changes had brought considerable benefits to people with disabilities. Specifically, accessibility to buildings and public transport had been improved.

But InsiemeExternal link and other organisations representing the disabled argue the report cast a too favourable light on Switzerland‘s progress. The report is too heavily concentrated on laws and omits the practical problems implementing them, they say. In addition, the convention and other laws are too heavily focused on the physically disabled; while the needs of people with mental or psychological disabilities are not sufficiently addressed, they say.

Associations representing disabled people have launched a national action plaExternal linkn to push ahead with implementing the convention.

Translated from German

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.