50 years of the Helsinki Accords: Switzerland’s role between the blocs

Switzerland played an important role in the adoption of this pan-European set of rules in the 1970s. How did the landmark agreement come to life and give rise to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)? We trace its roots with insights from a historian and firsthand accounts from Swiss and Polish diplomats.

In the middle of the Cold War, countries on both sides of the Iron Curtain agreed on a set of common fundamental values. Switzerland played a “leading role” in mediating between the blocs on human rights issues, according to a member of the Polish delegation present at the time.

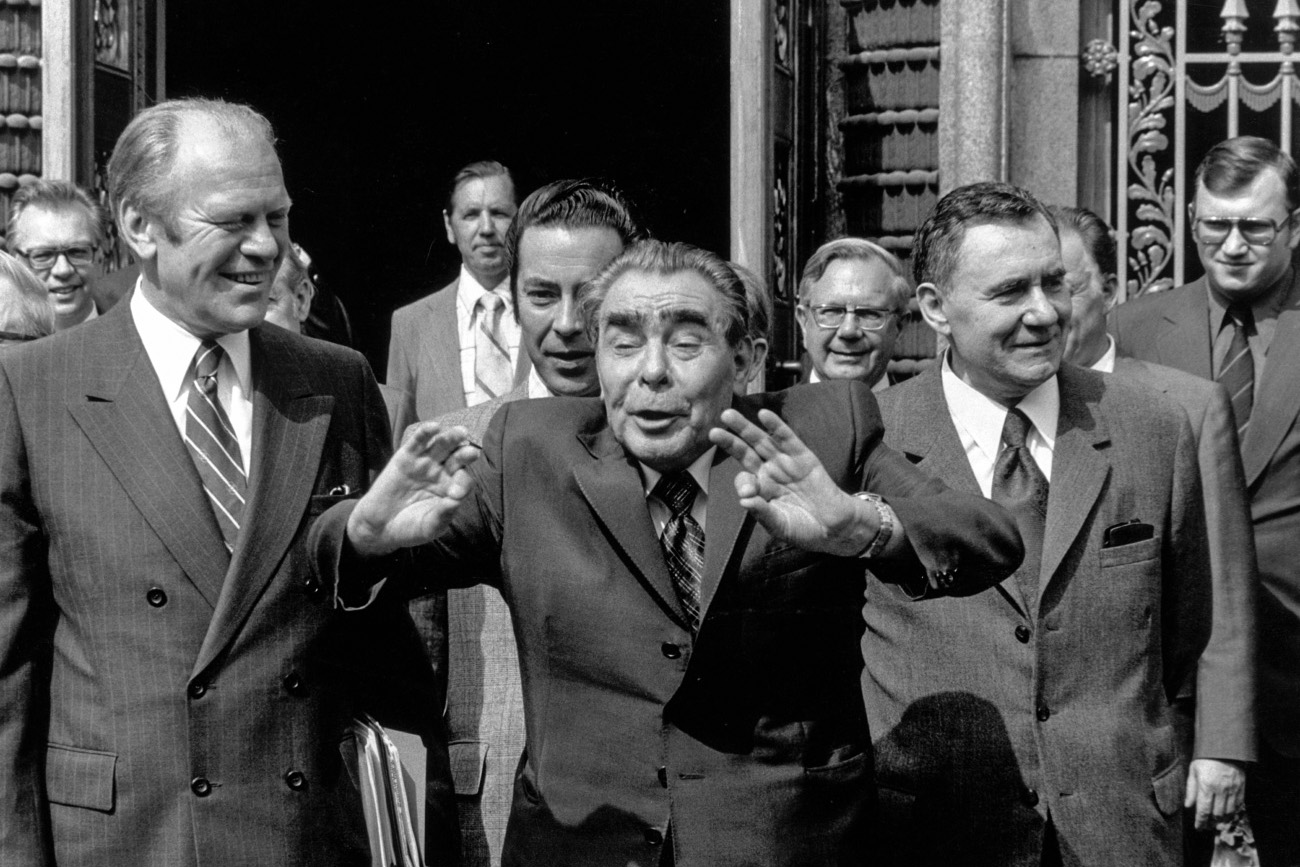

Thirty-three European states, the US and Canada agreed on state sovereignty, inviolability of borders and human rights when they signed the Helsinki Accords in the Finnish capital on August 1, 1975. They committed themselves to respecting the borders of other states and not interfering in internal affairs, resolving disputes peacefully, co-operating economically and respecting human rights.

This was the result of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE). In this multilateral political forum, East and West engaged in dialogue for the first time since the beginning of the Cold War.

How did the Helsinki Accords come about, and what role did Switzerland play?

All of Europe at the table

At the end of the 1960s, the Soviet Union, together with the other Warsaw Pact states, proposed convening a conference on security and cooperation in Europe. The first conference was held in Helsinki in 1973. The negotiations for the Helsinki Final Act took place in Geneva from 1973 to 1975. The signing of the “Helsinki Principles” went down in history as the high point of the détente policy of the 1970s.

Hans-Jörg Renk, who at the time participated in the negotiations as a young diplomat for Switzerland, recalls an atmosphere of genuine enthusiasm.

“It was exciting new territory for us,” he says. “Getting the whole of Europe, East and West, to sit at one table was remarkable.”

But the states were pursuing different objectives at the CSCE. “The main aim for the Soviets was to legitimise and consolidate the status quo ante,” explains Adam Rotfeld, a diplomat who was a member of the Polish delegation in Helsinki in 1975 and briefly served as Poland’s foreign minister in 2005. “They wanted the OSCE Final Act to be considered as the new type of European Peace Treaty – 30 years after the end of Second World War.”

The West, on the other hand, agreed to the CSCE on condition that, alongside economic and security policy, human rights would also be discussed.

“This proved to be a Trojan horse for the Soviets,” says Thomas Bürgisser, a historian at the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland (Dodis) research centre. “The member states of the Warsaw Pact, but also dissidents, were from then on able to invoke the Helsinki Accords.” For example, the human rights organisation Moscow Helsinki Group, which was active in the Soviet Union from 1976 to 1982, and the Czechoslovakian civil rights movement Charter77, which made a significant contribution to the success of the Velvet Revolution in 1989, called attention to the Final Act.

Switzerland’s mediator role

For Switzerland, participation in the CSCEExternal link, which it was initially sceptical about, was an important step towards opening its foreign policy. Before joining the UN in 2002, this was the only genuinely political multilateral forum in which it participated.

Together with Austria, Finland and Sweden as well as Yugoslavia, Cyprus and Malta, Switzerland belonged to the group of neutral and non-aligned states (N + N). Within this group, Switzerland “played a leading role,” according to Rotfeld, presenting itself as the “honest broker”, particularly with regards to human rights and humanitarian concerns, which were considered “third-basket issues” by the CSCE.

Not only did some of the negotiations happen in Geneva, but Swiss diplomats were also able to mediate as neutral actors between the US and the Soviet Union when negotiations threatened to come to a standstill. “Ultimately, however, the success of these negotiations depended above all on the willingness of the two blocs to compromise,” Bürgisser says.

After the signing of the Final Act, the Swiss foreign ministryExternal link emphasised that this was just the beginning of the real work. Negotiations continued at subsequent conferences, although the East-West dialogue stalled time and again. “At the second conference in Belgrade in 1977/78, the diplomats left without having reached any substantial decisions,” Bürgisser says.

In the 1980s, under Foreign Minister Pierre Aubert, Switzerland developed an independent stance on human rights policy for the first time and became an increasingly assertive advocate for these issues. When martial law was imposed in Poland in 1981, Aubert spoke of a “tragedy for the Poles” in an unprecedentedly harsh speech, criticised the socialist regimeExternal link and called for the CSCE conference to be suspended.

More

What does the future hold for Swiss neutrality?

An era of peace?

A new era began with the collapse of the Iron Curtain. The non-aligned order was sealed at the special summit in Paris in 1990 with the Charter of Paris for a New Europe, in which the states committed themselves to democracy, a market economy and co-operation.

“Paris was the last summit where the optimistic spirit of the early years was revived,” recalls Jerzy Nowak, a former CSCE diplomat who had also taken part in the negotiations in Geneva from 1973 to 1975 as a member of the Polish delegation. “At the follow-up conference in Budapest in 1994, there was already a feeling that European cooperation would not be easy, especially where Russia was concerned.”

In the years that followed, it became clear that Russia would hold on to its regional supremacy. The wars in the former Yugoslavia also showed that the dream of an “age of democracy, peace and unity”, as proclaimed in Paris, was an illusion.

“The CSCE would actually have been predestined to take on a central function as a large pan-European organisation after the end of the blocs. But it always lagged behind developments,” Bürgisser says. It was not until the 1990s that the conference was institutionalised and an annually rotating chairmanship was established. Since then, the General Secretariat and Permanent Council have been based in Vienna. In 1995, the organisation was renamed the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

The limits of diplomacy

Switzerland’s role also changed in the 1990s. “At the Paris Summit, the group of neutral and non-aligned states played an important role for the last time,” says Marianne von Grünigen, who led the negotiations in Vienna as head of the Swiss delegation together with Finland and Sweden. “With the end of the blocs, the N+N group also dissolved and neutrality became less important.”

Nevertheless, Switzerland continued to endeavour to participate in multilateral diplomacyExternal link, taking part in fact-finding missions in the break-up of YugoslaviaExternal link and the peacekeeping mission in Nagorno-Karabakh. In 1996, Switzerland even assumed the chairmanship of the OSCE.

More

Our weekly newsletter on geopolitics

In 2014, Switzerland once again assumed the chairmanship of the OSCE. The Helsinki Accords were crumbling at the time due to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine. The fragile Minsk I and II ceasefires were negotiated under the auspices of the OSCE and the leadership of the Swiss diplomat Heidi Tagliavini. Here, too, what had already emerged in the Yugoslavian wars became clear: “Ultimately, the OSCE’s decisions are toothless,” Bürgisser says, “because it doesn’t have its own army, nor can it impose sanctions”.

All decisions are subject to consensus. This has allowed Russia to put the brakes on many things since the start of its war of aggression in 2022. For example, the OSCE has been operating without a regular budget for three years. “In its entire 50-year history, the OSCE has never been as blocked as it is today,” Bürgisser says.

With its 57 member states, the OSCE is currently the only European organisation in which Russia is still involved. Switzerland will take over the chairmanship for the third time in 2026.

What can Switzerland achieve with its chairmanship? Former OSCE Secretary General Thomas Greminger describes the possible scenarios:

More

What Switzerland can achieve with its 2026 OSCE chairship

Edited by Benjamin von Wyl/ds. Adapted from German by Catherine Hickley.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.