Yoshi travels from Japan to Switzerland to die

A Japanese man came all the way to Switzerland to die. SWI swissinfo.ch accompanied him on the final part of his journey. This is his story.

It’s a Wednesday afternoon and there is a light drizzle, not the usual early summer weather. Yoshi* appears in a wheelchair with his parents at Zurich Airport. Laboriously, with the help of two sticks, he heaves himself out of the wheelchair and climbs into a taxi that takes him to Basel.

“I am so relieved we made it,” he says, looking out of the car window at the countryside.

The journey came about quickly. Just two weeks ago, he decided to take this flight. A Basel-based assisted suicide organisation, lifecircle, had already given him the greenlight to come to Switzerland and end his life three years ago. He had wanted to hold off until 2022 but was forced to make the trip in June after his condition worsened.

The deterioration in his health was as fast as it was dramatic, gaining speed like a wrecking ball rolling down a hill. “The numbness in my throat and on my tongue got worse,” he said. “I couldn’t swallow solids anymore. I also found it difficult to move my fingers. I could feel that my life was coming to an end.”

Assisted suicide is illegal in Japan. He had to get on the plane before he could no longer move his body, because otherwise it would have been too late. He had to convince his parents too. He wanted them to accompany him. At first, they opposed his plan.

He suffered severe pain in his lower body during the 12-hour flight, the last chance to see the world from above. After checking in at a hotel in Basel, he lies on a reclining chair with wheels and a headrest. There is no opportunity for sightseeing in this foreign city. He stays in the hotel room, uses the bathroom, and sleeps briefly.

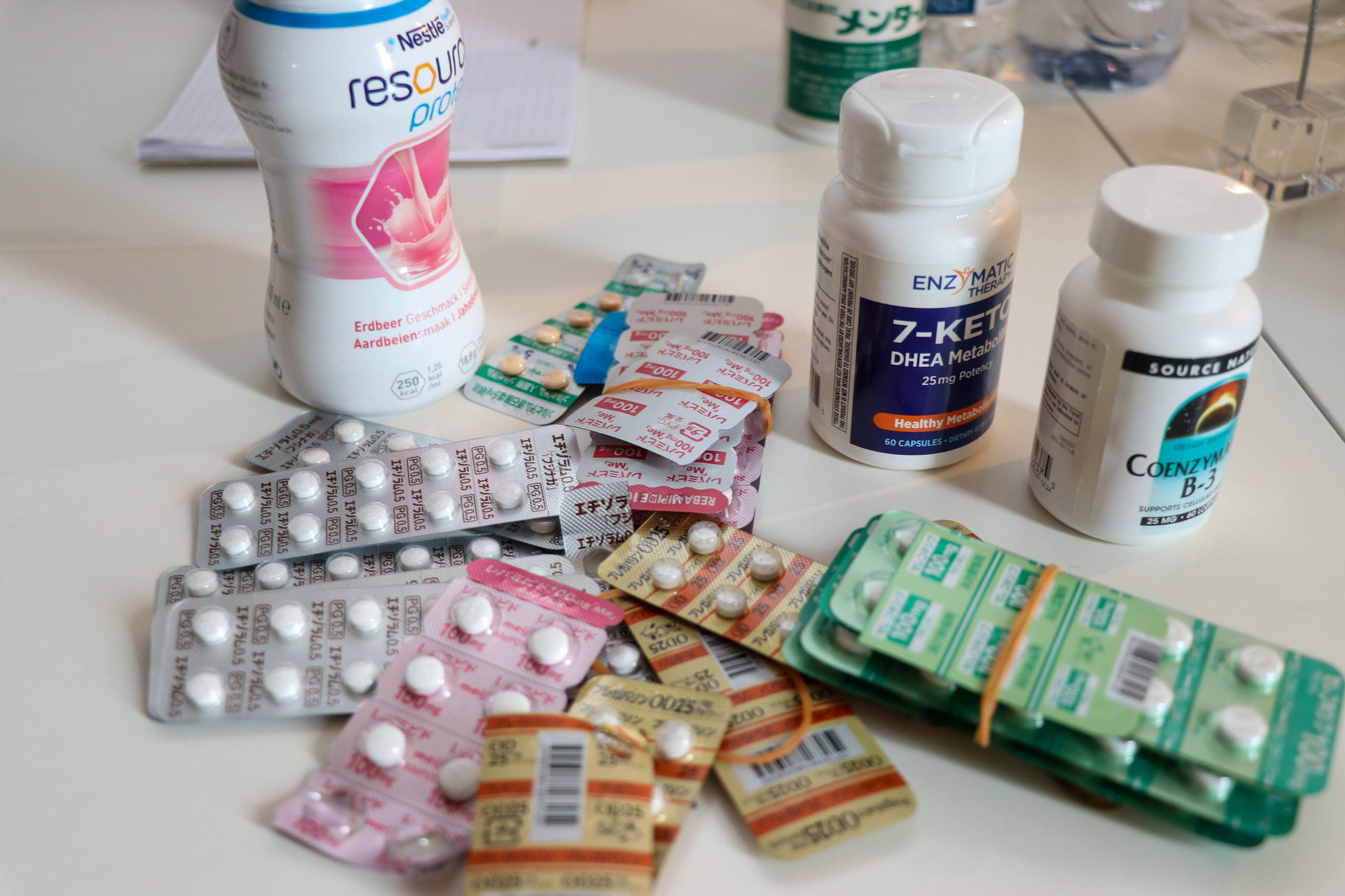

Settled on the recliner, he turns to his everyday companions: sleeping tablets, painkillers, and a medicine to counter numbness. “My core muscles have deteriorated considerably,” Yoshi says. “My internal organs have less support. They touch nerves, which causes severe pain.

Recently he has been unable to sleep for more than three hours at a time. Even with sleeping tablets, he wakes up every couple of hours. As soon as they start to wear off, the pain startles him awake.

Yoshi can only consume drinks containing food supplements, such as yoghurts or broth. He finds no pleasure in swallowing drinks just to obtain the necessary calories and nutrients to keep his body functioning.

Refusal to live without dignity

Yoshi is a single, 40-year-old office worker. In Japan, he lived with his parents in the east of the country. The first signs of his illness manifested themselves five years go. He had constant pain in his knees and could no longer stand on tiptoe.

An annual medical showed unusual liver values. After an examination, his doctor told him his muscles were “wasted.” The diagnosis was possible “motor neurone disease (MND).”

MND is a rare condition that progressively destroys motor neurons that control voluntary muscles. Its most common form is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Sufferers lose the ability to move at will. In the end, breathing becomes difficult. Death is inevitable.

Yoshi did not get a conclusive ALS diagnosis, but ALS symptoms have gradually taken over his limbs, robbing him of the use of his hands, his abdominal area and his throat and tongue. Videos and blogs by ALS patients prompted him to think about the end of the road.

“I do not want to dissuade someone who is carrying a ventilator from continuing to fight,” Yoshi says. “But I don’t want to live without dignity.” Two years later, in April 2018, he got in touch with lifecircle. It didn’t take long for him to get approval.

At the end of May this year, he could still walk about 200 metres with the help of sticks. He was able to work from home for the company that had employed for 13 years. And he enjoyed his mother’s homemade dinners. But those vestiges of normality evaporated as his health took a sharp turn for the worse.

No use to society

Back in Basel, Yoshi is nervous. He is due to meet two lifecircle doctors. Even though the approval for assisted suicide has already been given, this can be rescinded if the doctors find that the patient lacks the capacity to make judgments or is under the influence of a third person.

It is 9.30am. Yoshi leans back in his wheelchair and stares silently at the doors. Soon a doctor arrives. Her name is Erika Preisig. Yoshi answers her questions on his current condition and how he came to consider assisted suicide. He chooses his words slowly and calmly.

In his second conversation with another doctor, Yoshi’s work comes up. “You stayed in your job until shortly before your journey?” the doctor asks, with a surprised expression. “It was very important to me to make a contribution to society. But my disease doesn’t allow me to do that anymore. I feel as though I have no value.”

The two conversations last more than three hours. “From a medical perspective, there is no reason to oppose your assisted suicide,” the second doctor declares. Yoshi’s nervous expression eases. His assisted suicide is planned for Saturday. Today is Thursday. He wants to spend the rest of his time with his parents.

He tells them about the appointment. They were waiting in a separate room. His mother asks once again. “Are you sure you don’t want to change your mind?”

Unbearable pain

The disease has left Yoshi with little time left. In the evening he feels a dull discomfort in his lower body. That is a familiar warning of more severe pain to come. But this time they come in waves of unprecedented intensity. He takes more sleeping tablets than usual just to sleep. But he wakes up three hours later in excruciating pain.

“I can’t bear it any longer,” he says, turning to phone Dr. Preisig.

Friday morning begins with an apology to his parents for having to bring the appointment forward. They are now less adamant in their opposition to his course of action.

Yoshi can no longer sit in the wheelchair. “I have to conserve my energy,” he says, hauling himself onto the edge of the bed and letting his upper body sink backwards onto the mattress. “It is less painful like this.”

He waits. He will be given a new appointment.

“I have no Plan B or Plan C”

Why Switzerland?

“Because I want to die with human dignity. Breathing, eating, defecating and communicating, these are the basics of life. As I can’t do these anymore, I am making the right decision to end it,” Yoshi explains.

His family sees it differently. His mother begs. “I want you to live no matter what.” But that ignores his pain and his dignity, Yoshi says. “Patients like me don’t want to live in a vortex of pain. We don’t want our families to be so cruel.”

Yoshi believes assisted suicide benefits society. “If a patient with an incurable illness wants to die and can end his life, then enormous medical resources can be devoted to someone else,” Yoshi says. “For me that is a very ethical act.”

But many societies have come to a different conclusion and banned assisted suicide. “Why is the decision to give someone a ventilator acceptable? But assisted suicide isn’t?” Yoshi wonders.

He hopes that assisted suicide for patients like him will one day be legalised in other parts of the world “so that patients can die peacefully at home”.

There are three hours to go until the assisted suicide appointment. He has no doubts. “If I had a curable disease, then perhaps I would try to go on. But I have neither a Plan B nor a Plan C.”

Last words

It is 1.45pm on Friday, just two days after his arrival. The sun is out after days of rain. He and his parents take a taxi to the lifecircle building near Basel. Preisig is waiting for them. She takes the family to a spacious room with a single bed, a big table, and a sofa. Everything is bathed in summer sunlight.

Yoshi sits in a wheelchair at the table and signs one paper after another, an application for a death certificate, a declaration of consent for assisted suicide and one for cremation. Then he smiles. “Thank you. I am ready,” he says.

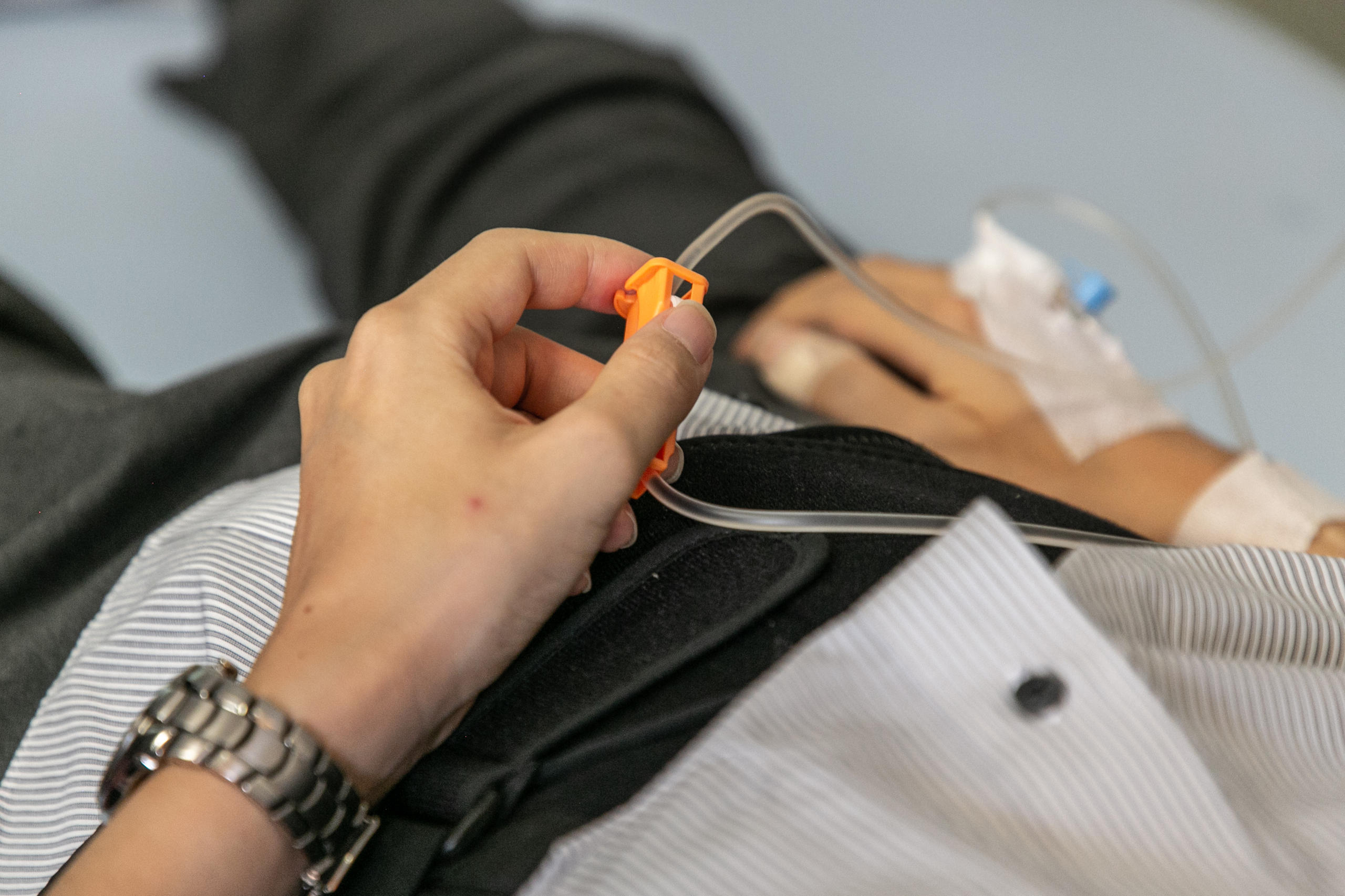

At 2.45pm Yoshi takes off his shoes and lies on the bed. Dr. Preisig injects a needle into the back of Yoshi’s right hand. His mother stands on his left side and strokes her son’s shoulder repeatedly and tenderly.

It is time to say goodbye. His father says, “Thank you for all the years you lived with us. You have always been precious to us. Have fun in heaven. We’ll be there soon.” And smiles.

Yoshi returns the smile. “I will wait for you,” he promises.

The intravenous bag is filled with a fatal dose of the sedative pentobarbital natrium. Everything is prepared.

It’s exactly 3pm. Yoshi says, “OK, then I am off!” Without hesitating, he opens the valve of the drip.

The deadly drug flows slowly through his body. Yoshi laughs: “Is it working? I can’t feel anything,” he says in a guttural voice, perhaps to hide his nervousness.

Thirty seconds later, there are four little breaths like snores, his last sounds.

As Preisig had explained beforehand, he has fallen into a coma. Three minutes later, the doctor lays a stethoscope on Yoshi’s chest and checks his pupils. She says quietly: “Yes, he has gone.”

“No pain?” asks his father. Presig lays her hand on Yoshi’s and says. “Yes, no more pain.”

The hand is still warm.

*name changed for the article.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

His choice would be. It's not wrong.

It is better to live longer if the disease is curable, but I don't deny prolonging life, but his choice is also the right one.

I work in a home for the elderly.

I'm not going to go into details because it would be personal information, but I'm going to mislead you a bit.

There are many around 100 years old who cannot communicate and can only open their mouths. On top of that, some patients are difficult to feed because they won't open their mouths even if you ask them to.

Personally, I do not think it is necessary to feed the patient if he or she will not open his or her mouth.

However, supervisors and senior staff who think they are good, right and kind should put food in the patient's mouth. They tell you to put the food in your mouth. They tell them to eat.

Some even tell them to put the food in their mouths or throw it in their mouths.

The same is true at the company I work for now.

There are still people who get upset that they can't get people to eat because of poor caregiving skills or talking to them.

There is no way a 100-year-old can eat a whole meal.

There are people who can eat, but they are reprimanded, so we have to force them to eat.

They can digest it and it nourishes them, so they haven't died, so they certainly have a long life.

A lot of people want to record that I'm feeding them three whole meals a day even when they're around 100 years old, but there are bedridden elderly patients who have to provide more than I do and eat more than I do because of legal nutritional issues.

To be honest, sometimes I think to the healthcare providers that if they want to go that far, they should put a tube in my mouth and pour the food down my throat.

There are those who are on intravenous nutrition, but some of them die after a few years because they can no longer absorb nutrients.

I myself live on a complete diet from time to time, so I don't deny the effectiveness and adoption of nutritional diets, even though prolonging life is a personal matter.

However ...

In the case of patients with a cervical nutrition, there is often no ego, only family members, doctors and money such as pensions are involved, and there are those who do it to prolong life, so it is not always clear what is just.

Some family members really want to prolong life, and we don't know what their true intentions are.

I can't deny families who want to prolong life.

I think it is difficult to operate euthanasia, but I also think that longevity is not the only thing that is good and the wishes of the patient should be respected.

I'm often warned at work that I'm an excuse-making bastard.

I want people to know that there are many medical professionals who think it's wonderful to force a person to live a long life by forcing food into their mouths.

I'm not saying euthanasia is a good idea.

I don't want people to condemn those who choose euthanasia.

彼の選択はありだろう。間違ってない。

直る病気なら長生きしたほうがいいけれど、延命を否定はしないが、彼の選択も正しい。

高齢者施設で勤務してる。

個人情報になるので、詳細を書かず少し誤魔化して書くけれど。

意思疎通ができず、口しか開けることができない100歳前後は多い。その上で、声をかけても口を開けないので、食べさせることが難しい患者もいる。

個人的にはご本人が口を開けないのなら、食事をさせなくても良いとは思っている。

しかし、自分はいい人で正しいし優しいと思い込んでる上司や先輩がちゃんと口に食べ物を入れ込め。食べさせろ。と指示を出す。

ちゃんと、口に入れ込めろ、ちゃんと放り込めという言い方で指示する方までいる。

今勤めている法人もそうだ。

食べさせられないのは、介護技術や声掛けが悪いからだとキレる人もいまだにいる。

100歳でご飯全量食えるわけねえだろうよ。

食べれる人もいるけど、叱責されるのでかなり無理にねじ込んでる。

消化できて栄養なってるから死んでないから、確かに長寿よだね。

100歳前後でも 1日3食を全量食べさせてると記録したがる人は多いのだが、法律上の栄養の問題で健康な私より提供料も食べる量より多くしなければならない寝たきり高齢患者もいる。

正直そこまでいうなら口に管をつけて食事流し込めよ、うぜえなと医療機関に思う時もある。

けいかん栄養の方もいるけど、数年で栄養を吸収できなくなって亡くなる方もいる。

私自身完全食をたまに食べて生活するので、延命については個人の問題としても栄養食の効果と取り入れは否定していない。

ただ

けいかん栄養の患者に場合、自我がなく家族だけに医師や、年金などお金が絡んでる場合もあり、延命でやる方もいるので、何が正義かわからない場合も多い。

本当に延命を望んでる家族もおり、真意はわからない。

延命を望む家族を否定はできないけど

安楽死の運用は難しいと思いつつも、長寿だけがいいわけではなし本人の意思も尊重すべきと思う。

よく職場で言い訳野郎と注意をされるのだけど

無理やり口に食事を詰め込み長生きさせることを素晴らしいと思ってる医療者も多いことを知ってほしいし。

安楽死を良いとは言わないけど

安楽死を選んだ人を非難して欲しくない。

I would like to register for Death with Dignity.

Can I do that now?

尊厳死の登録をしたいのですが

今はもうできないのですか?

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.