The Swiss start-ups embracing the cooperative model

The cooperative business model is a rare choice for young Swiss entrepreneurs. Swissinfo visits three start-ups that are bucking the trend to learn what drove them to this set-up.

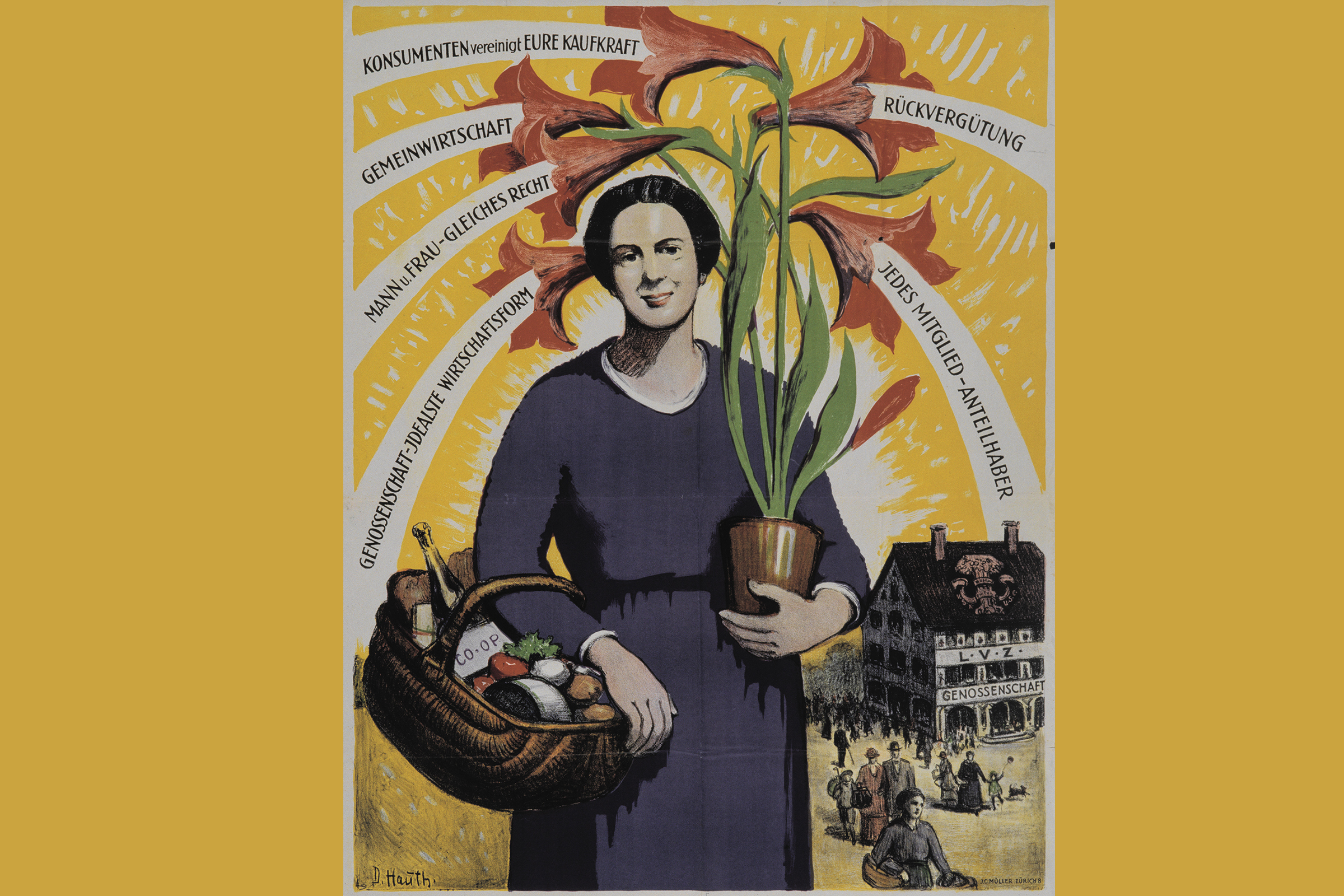

In Switzerland cooperatives are synonymous with retail giants such as Coop and Migros. Among young entrepreneurs launching start-ups, however, the prevailing sentiment is that, as business models go, cooperatives are slow.

In fact, cooperatives are less likely to go bankrupt than public limited companies and remain stable during economic fluctuations. The Swiss have trust in them but also perceive them to be “not very innovative”, according to a 2020 report by Idée Cooperative, an umbrella organisation for cooperatives. That could well explain why this model is not popular among young people: those who want to make money with their start-up set up a public limited company.

More

Some businesses are bucking the trend, however. From food to music, the entrepreneurs behind these start-ups see only advantages in embracing the cooperative model.

A small food cooperative in the capital

Tucked away on a quiet residential street in the capital Bern, Güter has shelves stacked with food and hygiene products. Two members of the cooperative are piling up freshly delivered vegetables between large barrels filled with rice and pasta.

Some of the milk bottles in the fridge are being sold at half price. The discount stickers are the only thing that calls to mind a conventional supermarket. Many larger Swiss retailers operate as cooperatives, even if this is rarely obvious during a shopping trip. But Güter is different. Only members are allowed to shop here, and they are required to work one shift of two to three hours at the shop each month.

Members join the cooperative for idealistic reasons. “We want to contribute to the democratisation of our economy,” says Nicholas Pohl of Güter. “Our members can experience how beautiful cooperation can be.”

By requiring its members to do voluntary work, Güter avoids distribution costs, which in turns allows the cooperative to offer a similar product range as organic shops, but at lower prices. This works for some products, such as hygiene articles. But the price difference for other items is small, especially given the limited quantities such a small shop can procure.

“Overall, Güter customers save between 10% and 20% compared to what they pay in organic shops,” Pohl estimates. Another sign of Güter’s social responsibility is that every shopper can donate a percentage of their purchase to low-income cooperative members, who can then use the credit to do their shopping.

Güter has only just opened its doors. The owners are still figuring things out. Big co-ops in the United States such as Park Slope Food Coop in New York have served as models for the food co-op in Bern.

“Cooperatives stand for democratic values and economic self-sufficiency,” says Pohl. “But we don’t see our store as part of a big cooperative movement.”

The cooperative model is “unfortunately not a seal of quality”, he adds. “Cooperatives have the potential to grow into large profit-oriented businesses.” His shop has no plans to follow the big Swiss retailers.

A record label with heart

The German-language daily Neue Zürcher Zeitung once described Red Brick Chapel as a self-help organisation. Despite its name, this business has nothing to do with the Salvation Army or any other church organisation.

Red Brick Chapel is the only Swiss record label that is organised as a cooperative.

“This is the biggest difference with most of the European record labels – the company belongs to the musicians and producers,” says Christian Müller, managing director of Red Brick Chapel. The artists can help shape how the company develops and retain control over their music. “They decide what happens to their music after production and how they are exploited financially.”

Red Brick Chapel has had some success. The Swiss indie band Mnevis has more than one million followers on streaming platforms in Germany alone. The folk singer-songwriter Long Tall Jefferson reaches similar numbers. Pop group Alois even landed on an American playlist, making their music available to a wider audience.

In the beginning, it was not a conviction about cooperatives, but a will to preserve and distribute control to musicians, which drove the founders. Müller, however, has since become a fan of cooperatives.

More

Working as a lobbyist for a Swiss supermarket giant

“I can’t imagine any other form of business for us,” he says. “Anything else would be ideology.” He thinks that cooperatives are the only suitable and logical business model for a group of people with common economic interests. In the age of streaming platforms, independent record companies see little need to employ more than a few people. But in Switzerland, when registering a cooperative, an application must list at least seven members. Müller thinks this is one of the main reasons why Red Brick Chapel is an exception.

More

Homeless to hip: How Swiss housing cooperatives developed

Cooperatives may not be the first choice for most start-ups, but Müller thinks they offer a big advantage: their statutes are flexible, which means that the members can determine how agile or democratic their cooperative is.

Swiss companies do not spring to Müller’s mind immediately when he thinks about cooperatives; he instead associates them with trendy US food co-ops. In Switzerland, he thinks of the “big ones”, which he says “are no longer recognisable as cooperatives” and have nothing to do with his idea of what a cooperative should be.

A bike courier business with shared responsibilities

Young people on bicycles clad in fluorescent gear weaving in and out of heavy traffic to deliver urgent parcels have become a familiar sight in Swiss city centres. More and more international bicycle meal-delivery services have popped up in the country in recent years. But they are not known for their fair working conditions. Home-grown bike courier businesses, on the other hand, have embraced the cooperative model.

One of them is Veloblitz, which employs 120 bike messengers in Zurich clad in black and yellow uniforms. Managing director Simon Durscher was not there when the company was set up in a shared flat in the city in the 1980s.

“The founder of the company once told me that he never wanted to set up and own his own business,” he says. “He saw entrepreneurship as a potential, but he was keen to share the responsibility right from the beginning.”

Durscher understands why cooperatives are considered sluggish compared to other businesses: “In my ten years at Veloblitz, I’ve heard a lot of opinions about what the company is or should be. Here, people get together and create an employer.”

The basic idea behind Veloblitz is that employees become co-owners. But some former members are still part of the cooperative, while some employees do not become members. Their views are taken no less seriously because of this.

More

When cooperatives wanted to prevent a world war

Veloblitz, Durscher says, is not hierarchical and responsibilities are shared. “We are not a grassroots democracy – that wouldn’t help us,” he says. “Not everyone can have a say in everything.” It is better to distribute tasks and decisions in small teams rather than in a large plenary assembly, he adds.

Durscher thinks that the “seven people rule” could be a reason many start-ups choose not to become cooperatives. Yet co-ops can offer a pragmatic advantage to many young entrepreneurs. “Unlike public limited or limited liability companies, cooperatives do not require seed capital,” he says. “They allow people with limited finances to set up a business.”

Edited by David Eugster. Adapted from German by Billi Bierling/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.