What deportation opponents in the US can learn from Switzerland

Did Americans vote for the deportation raids in churches, hospitals and schools? Historian Lauren Stokes points to the lessons of Swiss direct democracy.

Since US President Donald Trump took office in January 2025, he has realized his campaign promise to carry out deportations and evidently relished in doing so. While officials claim that they are detaining “the worst of the worstExternal link”, journalists and researchers have demonstrated that most detained people have no prior criminal recordExternal link – in the majority of cases, it appears that their only crime was breaking immigration law. The point appears to be deporting as many as possible, as publicly as possible.

The current administration has overturned previous guidance that kept enforcement out of sensitive locations such as churches, hospitals and schoolsExternal link. Arrests have taken place everywhere from daycares to citizenship hearings. Official and unofficial recording of such incidents has exposed Americans to the brutality of deportation enforcement.

James Schwarzenbach’s initiatives

Did Americans vote for this? Testing this hypothesis is difficult. US voting behavior is only a weak signal about any individual policy.

Switzerland, however, offers a unique test case for thinking about how democracies build consent for deportation.

The country’s referendum system gives voters direct say on deportation policies. Perhaps the most famous example came in June 1970, when the Swiss politician James Schwarzenbach advanced a proposal that the proportion of foreigners in Switzerland should not exceed 10%. While the details of the plan were unclear, had the proposal passed, it is estimated that 350,000 people would have had to leave the country.

More

Anti-migration initiatives have long tradition

The proposal drew 75% of eligible voters – at the time, only men – to the polls, where 54% rejected it. This initiative asked voters to consider a population target but did not consider the methods. Schwarzenbach himself claimed that the key would be the “voluntary departure” of most of the concerned foreigners. Because the referendum failed, the state never had to encourage “voluntary” departure or to test its limits.

Dubious claim about ‘voluntary’ departures

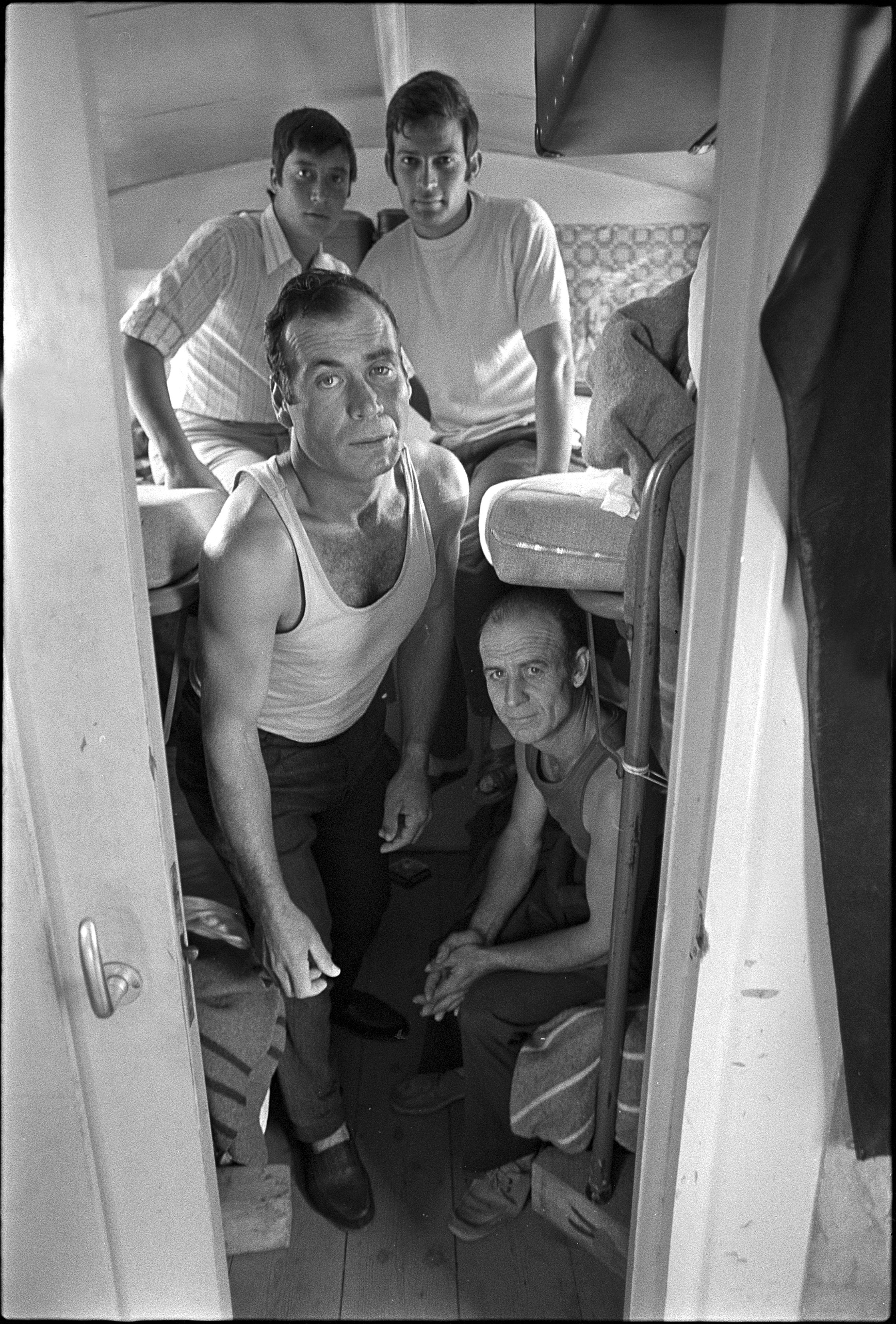

The claim that most foreigners would leave “voluntarily” was dubious. For one thing, conditions were already far from ideal. Switzerland recruited foreign workers across a range of industries but made their residence highly precarious, including by banning the migration of the children of “seasonal workers”.

While most parents left their children in the home country, a significant minority brought their children without authorization, so that perhaps 50,000 children lived as clandestine migrants of authorized parents between 1949 and 1975. The fact that tens of thousands of parents felt forced to make this choice rather than to leave Switzerland shows the profound difficulties involved in migration. And yet, they stayed anyway. How much tougher could Schwarzenbach have made their lives?

Similar referendums took place in 1974 and 1977. Supporters continued to stress the voluntariness of the measures they proposed. In a speech in favor of the referendumExternal link, rightwing politician Valentin Oehen complained that the press was sensationalizing the departures: “[…]400,000 foreigners are to be sent home, or rather, expelled. Why couldn’t they write: 400,000 foreigners are allowed to return home? After all, people generally like to go home if they have the opportunity.” Both attempts failed, each by a greater margin than the last. Since 1971, women were among the voters who rejected the idea.

Read here all our articles about the introduction of women’s suffrage in Switzerland:

More

The long road to women’s suffrage in Switzerland

Deportations carried out by Swissair

Even as Swiss voters were rejecting a hard cap on the foreign population, deportations were slowly becoming normalized in the background. Historians have discussed the late 1970s and early 1980s as a “paradigmatic shift” in Swiss deportation policy. The state began to track and computerize deportation statistics in 1982. Asylum authorities and the foreigner police began to coordinate with each other as the targets of deportation shifted from criminal foreigners to rejected asylum-seekers. The state also introduced pre-deportation detention for individuals deemed a threat.

National airline Swissair carried out many deportations; cantons that owned shares in the company could even book discounted deportation tickets. While some in civil society resisted these developments, whenever deportation became visible it also led to gains for rightwing parties. Switzerland carried out its first deportation by charter flight in November 1985. When a journalist discovered the operation, the Federal Department of Justice issued a press release justifying the action – horrifying asylum advocates but also empowering right-wing politicians to argue that the state ought to be deporting more aggressively. Some individuals even made death threats against politicians whom they perceived as weak on deportation.

My academic work has addressed the history of migration, and my current book project is a history of international civil aviation from the passenger perspective, including unwilling passengers: deportees. States in both North America and Western Europe used aviation to increase their deportation capacity in the 1980s and 1990s while keeping that expansion somewhat concealed from the public.

People’s Party referendums

In Switzerland, the Swiss People’s Party politicized asylum and immigration in the 1990s, becoming the country’s largest party. The People’s Party has launched a range of referendums on immigration issues, including two that specifically asked voters to consider deportation policy. In 2010 the party put forward a proposal on automatic deportation for foreigners convicted of violent crimes or welfare abuse. Posters promoting a “Yes” vote on the referendum showed white sheep kicking black sheep off the Swiss flag. Campaign literature invited voters to protect themselves from specific foreign threats, such as “Ivan S., Rapist – Soon Swiss?” or “Ismir” the welfare cheat. The fictive names and photographsExternal link referenced racist stereotypes about men from the Middle East and Eastern Europe. A total of 52.9% voted “yes” on this proposal.

In 2016 the People’s Party presented a second deportation referendum. This one proposed automatic deportation for foreigners who, within a ten-year period, committed two minor offenses such as cannabis possession, shoplifting, or speeding. This referendum failed, winning 41.1% of the vote. Its opponents successfully persuaded a majority that this form of state coercion was disproportionate.

An administration creates celebratory images of deportations

While the People’s Party mostly used fictive campaign material for its referendums, the Trump administration is producing propaganda based on real deportation efforts: White House social media accounts share celebratory images of deportation flights. Immigration agents film enforcement actions for use in jingoistic advertisementsExternal link encouraging people to apply for jobs as their colleaguesExternal link.

It’s all been confusing to watch as a historian. Much of my archival material comes from civil society groups that opposed deportation and that assumed that unveiling its operations would encourage others to oppose it as well. These documents tell a story of constant struggle over visibility – the state tries to hide deportation, the activists try to expose it.

Watching the United States gloat in its 21st-century expansion of deportation capacity, I’ve had the nagging feeling that my civil society actors were wrong, or at least not entirely right.

The Trump administration seeks to control visibility by producing so many images of what they want the public to see – the arrests and mugshots of those who can plausibly be called “the worst of the worst” – that those will numb us to the facts that they still want us to look away from. I can watch hours of footage of people being seized off the streets and planes taking off loaded with migrants, but the brutality of detention and the conditions inside those planes remain a black box. And nothing is more of a black box than life after deportation.

Is there a democratic majority in favor of deportations?

Despite evidence that most Americans reject the current escalationExternal link of deportation, it shows no signs of abating as the Trump administration enters its second year. The mass spectacle of deportation is one of the few campaign promises Trump can successfully keep, even as his promises to improve the lives of ordinary Americans increasingly ring hollow.

What do the Swiss referendums tell us about democratic consent for deportation? First, and most simply, that you can create a democratic majority in favor of deportations. But after being made, it can be unmade. In both series of referendums, the highest support for the mass removal of foreigners came in the first vote and ebbed thereafter. Second, voters in Switzerland did seem to distinguish between the kinds of crimes they wanted to see people deported for.

The People’s Party was successful in the referendum that promised to deport “the worst of the worst” but unsuccessful when it campaigned to expand deportation power over those foreigners who had merely had a traffic violation, a petty theft, or an immigration offense. Opponents of deportation successfully claimed that these people were part of their community.

Edited by Benjamin von Wyl/ts

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of Swissinfo.

Read more about the history of Switzerland’s views on refugees:

More

How Switzerland’s views on refugees have evolved

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.