Cambodia’s Tun Channareth renews fight for mine-free world in Geneva

Cambodian landmine survivor and activist Tun Channareth returned to Geneva to defend the Ottawa Convention, as the global treaty he helped champion faces withdrawal threats from several Eastern European nations.

“Do you like peace, yes or no?” In the austere Geneva International Conference Centre, Tun Channareth’s call rang out like a gunshot. “Yes!” replied the dozens of diplomats present. Long applause followed.

“It wasn’t part of my speech,” he confides, smiling a few hours later. “I improvised! But it’s easy to say you want peace. What we need is action,” he adds, clearly accustomed to empty diplomatic promises.

At 65, this tireless Cambodian activist has spent over three decades fighting against anti-personnel mines – horrific weapons that make no distinction between a soldier, whether friend or foe, and a child.

Channareth has first-hand knowledge of their horror. On December 18, 1982, at the age of 22, he lost both his legs when he stepped on a Russian-made mine on the border between Cambodia and Thailand. At the time, he was a young soldier in the Vietnamese army, fighting the Khmer Rouge in his native country – a choice he says was motivated by the need to be “fed and clothed” when he had nothing.

‘Don’t make me cry again in 2025’

More than four decades after losing his legs to a landmine, Channareth is still fighting. Fresh off a flight from Phnom Penh, he has come to Geneva to attend the intersessional meeting of the Ottawa Convention, which bans the use, production, and transfer of anti-personnel mines. This is a treaty he championed and watched become reality in 1997, but one that is now at risk as several countries threaten to walk away.

Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Finland – all neighbours of Russia or its military ally Belarus – have announced their intention to withdraw from the treaty in recent months. Russian aggression in Ukraine has prompted them to rearm, and they are refusing to rule out using an entire category of weapons.

>> Read our article explaining what is at stake if these states withdraw from the convention:

More

Why five European countries want to allow anti-personnel mines again

“I would never have imagined that countries would leave the treaty,” Channareth says bitterly. He is intent on doing his utmost to dissuade these states from formalising their withdrawal. His chances of success, he knows, are slim. But he still hopes to get a meeting with their diplomatic representatives in Geneva.

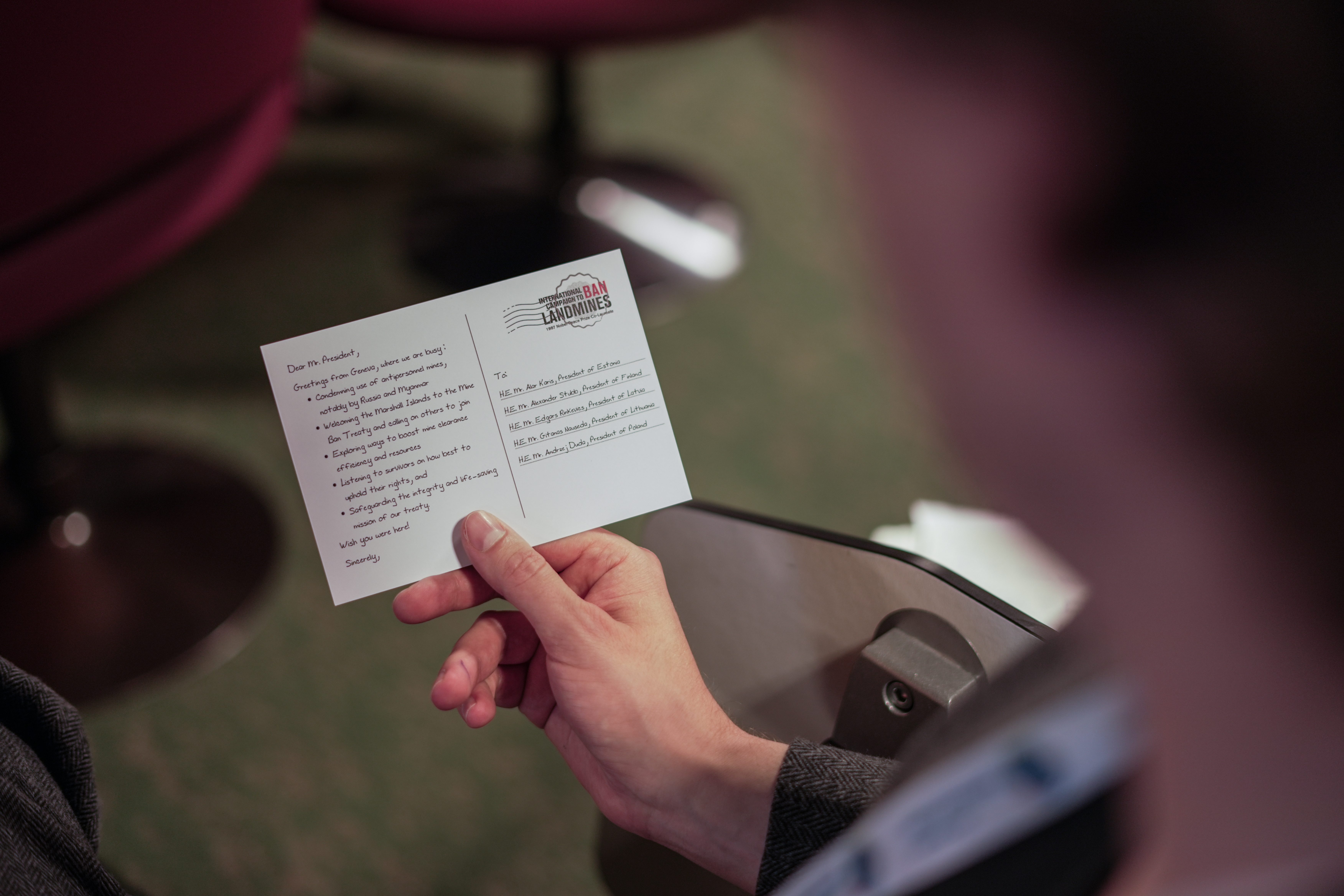

As soon as he finishes his opening speech, Channareth dashes between the rows of seats. Perched on the wheelchair he designed himself, he glides from one diplomat to the next. He hands each one a small card: “Don’t make me cry again in 2025. Don’t leave the Mine Ban Treaty.”

When a diplomat asks for a selfie, two representatives of Baltic countries discreetly head for the exit. Channareth quickly turns around and hands them his cards.

From death wish to Nobel Prize

Channareth grew up in a Cambodia ravaged by civil war, then genocide and crimes against humanity by the communist Khmer Rouge – atrocities that claimed the lives of a quarter of the population, including the activist’s father and his sister, who was 15 at the time.

Four years later, separated from the rest of his family, he fled across the border to a refugee camp in Thailand. There he discovered that men were not entitled to any help. “After three days without food”, he joined the Vietnamese forces.

Then came the accident. Overcome by pain, in the middle of the forest, he tried to put an end to his suffering with an axe, but the friend at his side prevented him. He was taken to hospital and his legs were amputated.

“I didn’t want to live any more,” he says, his head bowed. Lying in his hospital bed while his wife was expecting their first child, he had no prospects left. Years of misery followed.

It wasn’t until 1993 that the turning point came. In Phnom Penh, he joined the Jesuit Refugee Service, an American NGO, where he designed wheelchairs for landmine victims. He also worked with disabled children, encouraging them to lead active lives.

Cambodia is one of the most heavily mined countries, riddled with devices laid down over decades and conflicts. Since the 1970s, more than 65,000 victims have been recorded, including around 20,000 fatalities. Despite major demining efforts since the 1990s, an estimated four to six million landmines and other unexploded devices remain buried in the ground.

One day, while toiling in his workshop, Channareth heard the sound of an explosion nearby. “Probably a mine,” he said to his boss. Her response changed the trajectory of his life. “I have a new mission for you,” she said. “I want you to get them banned.”

He embarked on a frantic campaign. In less than a year, with the help of other survivors, he collected more than a million signatures calling for a ban on anti-personnel mines, which he presented to the Cambodian king and prime minister. He continued his commitment abroad, joining the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997.

“What prize? Why me? I’m just doing my job,” he said to his boss when she told him that he would be going to Oslo to collect the prize on behalf of the campaign with Jody Williams, the movement’s founder and coordinator. “I asked her if the medal was really gold and if I could sell it. She said no,” he recalls with a laugh. “I was poor, I needed money.”

But the real culmination of all his efforts came in 1999, when Cambodia ratified the Ottawa Convention. “I was very proud,” he says.

‘Do you want your children to look like me?’

Back to Geneva. Of the 193 countries recognised by the UN, 165 have now signed the Convention. Among those that have not are powers such as China, the United States and Russia.

“This campaign will keep going until my last day,” says Channareth, who dreams of a mine-free world. “My aim is to do everything I can to prevent governments from abandoning the convention. But also to encourage all those who have not yet done so to sign it.”

His argument is as simple as it is forceful: “I want to show them my wounds and ask them: do you want your compatriots, your children, to look like me? No? Then don’t leave the convention. Don’t mine your own country.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/sj/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.