Will we ever know the truth about the origin of coronavirus?

Getting to the truth about the virus behind the 21st century’s worst pandemic may be a mission close to impossible, with obstructed scientific investigations rife with conflicts. The consensus among virologists working in Switzerland tends towards animal-to-human transmission, but some say the theory of a leak from a Wuhan lab should be taken more seriously.

The window to investigate the matter is closing, warned the scientists who investigated the outbreak under a World Health Organization (WHO) mandate in an editorial External linkrecently published in Nature.

“It seems right now it is more important to find a culprit than to find the truth,” says Isabella Eckerle, a virologist and director of the Centre for Emerging Viral Diseases at Geneva University Hospital.

Another renowned Swiss virologist, Didier Trono of the Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), also believes that the issue has become more about politics than science. Trono is pessimistic about ever learning what really happened, despite the importance of this knowledge for preventing and managing future pandemics.

“We have to be prepared not to have a final answer because of the scientific difficulties and the political implications, but at this stage the likelihood of a transmission from animal to human remains high,” he says.

Hidden truths

The search for the origins of Covid-19 has been fraught with complexities and controversies. China has never been fully cooperative and transparent and has so far always denied access to complete data and samples, as WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus asserted in a rare public criticism of ChinaExternal link. He said the lack of transparency has hindered the WHO, which sent a team of independent researchers to Wuhan in January and February to carry out in-depth investigations. But the team spent the first 14 days in quarantine, only able to discuss with Chinese experts via video chat, according to the WHO’s account of the mission. That left just two more weeks for on-the-ground investigations, all of which were pre-planned due to the need for distancing and health monitoring.

Ultimately, despite the difficult collaboration with the Chinese government, the WHO dismissed the laboratory accident hypothesis in its global studyExternal link on the origins of SARS-CoV-2. The global health body labelled it “extremely unlikely” based on incomplete data.

Tedros later acknowledged the laboratory leak hypothesis had been ruled out prematurely, and Peter Ben Embarek, the Danish scientist who led the WHO’s scientific trip to China, recently admittedExternal link that Chinese officials pressured his team to drop the theory.

In the wake of such revelations and the study’s incomplete data, some WHO member states – including the US, the UK, Canada and Australia – strongly criticisedExternal link the Geneva-based health body for its negligence and China for its lack of cooperation and concealment of data. The scientific community also weighed in when a group of 17 researchers from around the world – including Richard Neher, a professor and expert on virus evolution at the University of Basel – called for the investigation to continue in a more objective and transparent manner in a letter External linkpublished in Science Magazine last May.

In the letter, the signatories argued that “the two theories [the spillover and the laboratory accident] have not been taken into account in a balanced way”, even though neither of them was supported by clear results. “We have to take both hypotheses seriously until we have sufficient data,” Neher tells SWI swissinfo.ch.

A question of probability

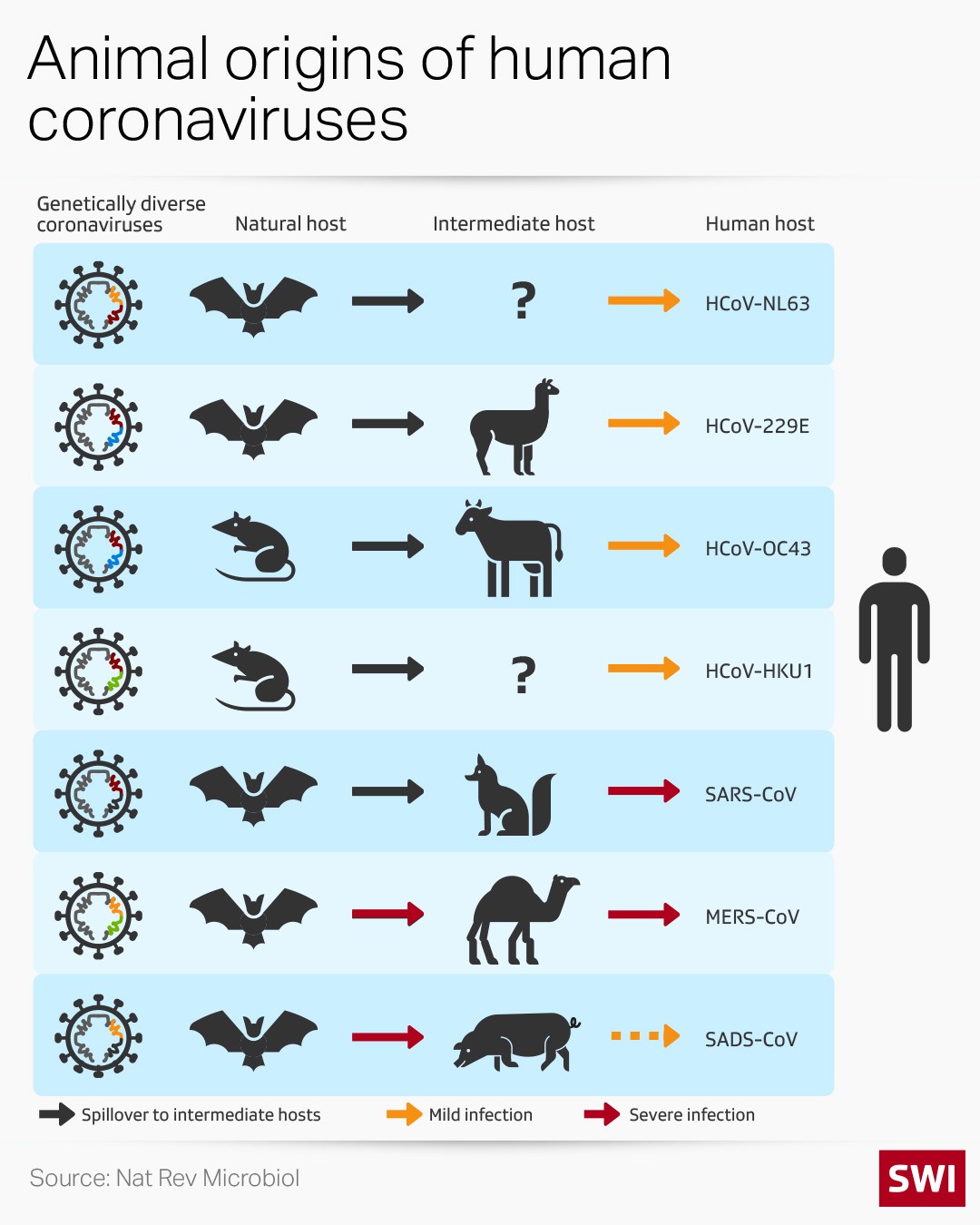

The WHO’s global study identified four possible pathways for the virus from the presumed animal of origin (horseshoe bat) to us: direct zoonotic spread (from bats directly to humans, considered likely), introduction through an intermediate host (from bats to another animal and then humans, considered very likely), the cold food chain (considered possible) or a laboratory accident (considered extremely unlikely).

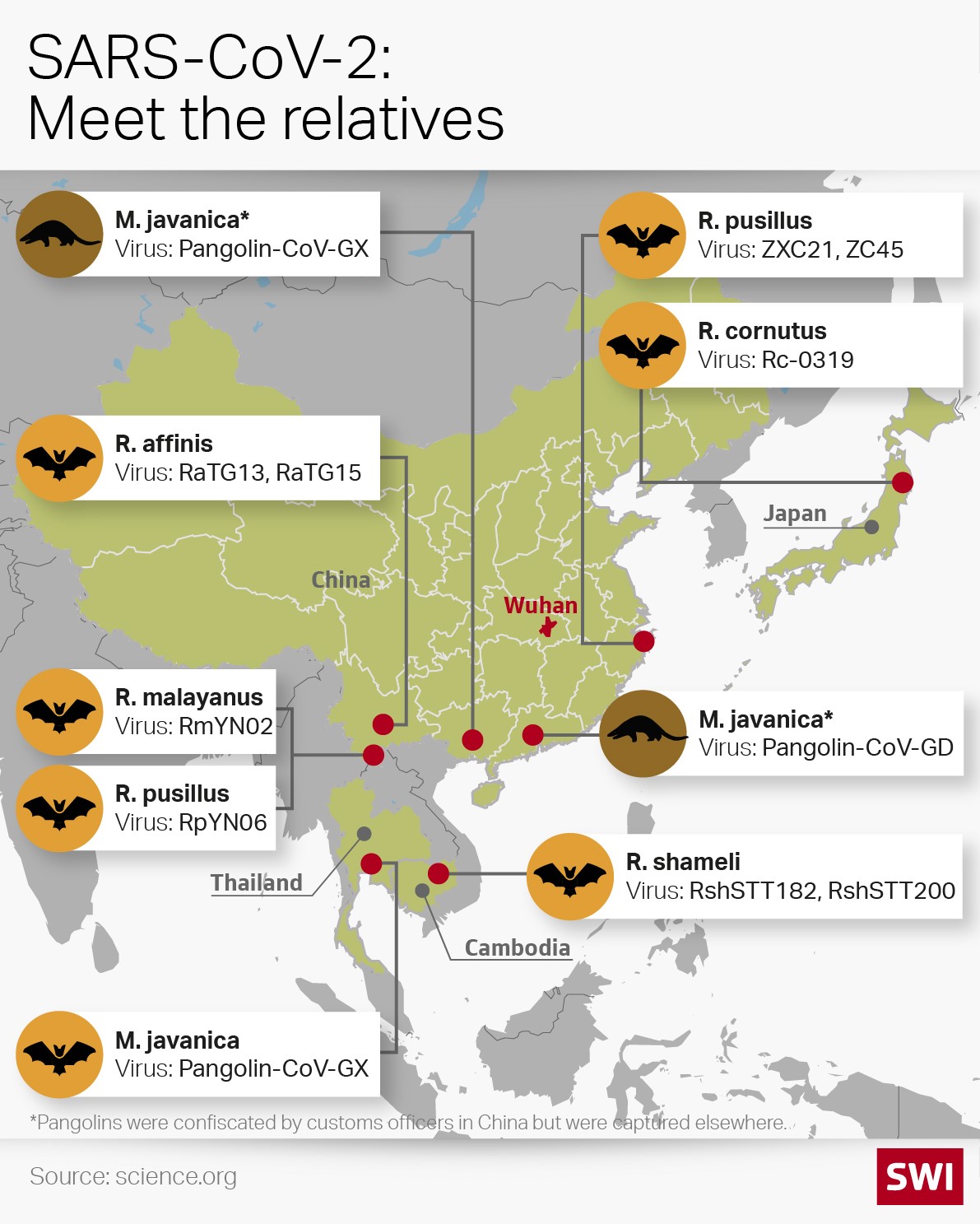

The intermediate-host hypothesis is considered very likely because, although there is a known bat coronavirus that is genetically close to Sars-Cov-2, the two viruses are separated in time by several decades. This would suggest “a missing link”, namely an animal belonging to another species that acted as a “bridge” between humans and bats, the WHO report says. Animals like pangolin, mink or civet have been considered as possible hosts, as they are susceptible to coronaviruses, but an intermediate host is yet to be identified definitively.

“It may never be,” argues Eckerle, adding that tracing the origin of a virus is challenging and time-consuming. “The search can take years, as was the case with SARS-CoV-1, and the host animal population may already be extinct,” says the virologist.

In the case of the SARS outbreak of 2002-2004, it took researchers about four monthsExternal link to identify civets as the intermediate host, but years to findExternal link a single population of horseshoe bats living in a remote cave that harboured all the genetic building blocks of the virus. Eckerle is not surprised that the WHO report did not provide more conclusive findings about the origin of SARS-CoV-2 given the complexity of the investigation.

What is known, however, is that many of the viruses currently circulating are the result of zoonoses, diseases that are transmitted from animals to humans and vice-versa. It’s a phenomenon set to increase due to human disturbance of animal habitats, such as deforestation and intensive animal husbandry. Meanwhile, laboratory incidents are rare, says Eckerle. In her ten-year career, she says she has never had an accident herself or witnessed one during an experiment.

“It is much easier to look for a scapegoat so that we don’t have to admit that our lifestyle might have been a big contribution to such a pandemic,” she says.

Neher, the author of the letter in Science, acknowledges that outbreaks are more likely to be generated by zoonoses but points out that laboratory accidents have happened before.

“Given the coincidence that there is a laboratory studying coronaviruses in Wuhan, this possibility should not be dismissed,” the expert argues, citing an absence of evidence to the contrary. The Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) is one of numerous sites around the world working on highly sensitive coronavirus research and maintaining a database of virus samples and sequences.

More

How the Swiss-based WHO BioHub is preparing for future pandemics

According to a US intelligence reportExternal link, three researchers at the institute sought hospital care in November 2019 after getting sick with a flu-like illness. This theory suggests that the staff members became infected with the virus because of faulty protective equipment or inadequate security measures before spreading it throughout Wuhan. But the WIV has not released any medical records that would confirm or deny that its staff members contracted the virus.

The lab leak theory could be dismissed if the intermediate host were found, states Neher. But he stresses that, despite the intensive search for the virus in animals on farms and in the wild, looking for a plausible link with the human coronavirus, “so far, no closely related virus has been found”.

Several factors about the trajectory of the WHO’s Wuhan investigation and the nature of Covid-19 itself have raised renewed questions about a possible lab leak. The first involves the presence of Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance in New York, on the panel of “independent and conflict-free” scientists selected by the WHO to investigate in Wuhan.

The EcoHealth Alliance in New York had financed research into coronaviruses conducted by Shi Zheng-li, one of the WIV’s leading scientists dubbed “Bat Woman” by the media for her work on bat coronaviruses. And Daszak signed a letter published in the Lancet at the very beginning of the pandemic, condemning the laboratory accident hypothesis and pressuring his fellow scientists to do the same.

Furthermore, Pascal Meylan, an infectologist and honorary professor at the University of Lausanne, calls a particular feature of the coronavirus “a bit suspicious” in relation to the theory that the virus could have been manipulated before it accidentally leaked.

Not only the SARS-CoV-2 features a cleavage site in the Spike protein for furin, a protein-cutting enzyme present on the surface of human cells, says Meylan, but it also encodes two arginin aminoacids, using the nucleotide codon CGG triplet (that is the nucleic acid language that specify aminoacids). Indeed, this triplet is favoured by human cells but rarely found in wild coronaviruses in bats.

Both of these features may suggest that the virus has been manipulated in the laboratory, using human cells grown in culture and humanised mice. While many coronavirus specialists have refuted this theory, saying that several members of the SARS-related coronaviruses possess furin cleavage sites, others called it a “smoking gun”.

“It’s not proof, but it’s a bit suspicious that there are these two typically human arginine codons in the middle of typical coronavirus codons,” Pascal Meylan told SWI swissinfo.ch.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!